NEW HAVEN, Conn. — For Anthony Kronman, achieving excellence has been a lifelong endeavor.

By the age of 30, the man who would one day serve as dean of Yale Law School had a law degree and a Ph.D. from the Ivy League school, after having completed an undergraduate degree at Williams College.

He’s been teaching at Yale for 40 years, and has thus witnessed first-hand what he says is a threat to the original intent of higher education. He has spent his entire life working to achieve excellence in academia, but said he’s worried “American excellence” is under attack.

It stems from an assault on the idea that some people excel at “being human” more than others, an idea originating from the writings of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. In other words, while humans are all intrinsically equal, how they live their lives is subject to varying degrees of excellence.

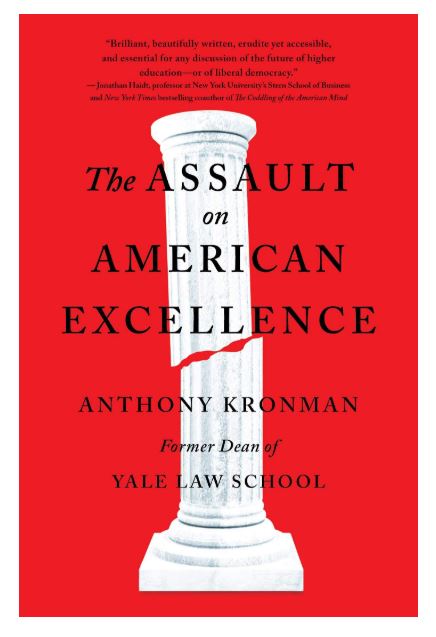

In an exclusive interview with The College Fix at his Yale office, Kronman discussed his forthcoming book “The Assault on American Excellence,” and criticized the current model of higher education, which predominantly views a college degree solely as a form of training for employment.

“I hope that the book opens a line of debate, of conversation, however passionate and intense, that will help to loosen the joints of what has for sometime felt like an increasingly immobilized machine,” he said. “If the book serves as a lubricant in that respect, it will have done everything I hoped.”

The book is billed by his publicist as taking the debate beyond colleges’ excesses of political correctness to identify a deeper problem — “that the demand for democratic equality threatens the very purpose of American institutions designed to prepare citizens for democratic life.”

“He argues that while equality in political life is vital, the unequal structure of colleges and universities — the push-and-pull of debate and challenge, and the necessary knowledge that not all ideas are created equal — is necessary in order to protect our political system. … Kronman argues that the equalizing impulse threatens the fabric of American democracy.”

Kronman then ties that concept into the argument that universities today have abandoned their belief that meritocracy and achievement are real and vital components of American excellence, and instead have embraced the concept of a radical equality that supersedes recognition of those who truly excel.

Using an analogy of a flute player, Kronman said some people are better at playing the flute than others. Aristotle applied the same principle to the notion of being human, arguing that some humans are more talented, driven and intelligent than others.

“Their capacity for being human is more active and engaged, more fully at work than the capacity for being human that others possess. They are fuller, richer, more developed human beings, just as the flute player who plays an excellent tune is a better and more developed flute player than the mediocre one,” Kronman said.

“For Aristotle, this seemed intuitively obvious, that there are grades of excellence in the work of being human, just as there are grades of excellence in the work of flute playing or any other activity,” Kronman said, adding his concern is that the modern university — and America as a whole — no longer accepts this.

Therein lies “The Assault on American Excellence,” the very title of his book.

Therein lies “The Assault on American Excellence,” the very title of his book.

“We accept grades of excellence in every narrow or limited pursuit, but not in the comprehensive work of being human,” the professor said. When the acknowledgement of excellence is lost, “no one is entitled to greater respect or admiration on account of their humanity than anyone else.”

At the core of his new book, which is set for release on August 20, Kronman leans heavily on the famous observation of American life in 19th century Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville’s book “Democracy in America,” which he called “an unsurpassed account.”

Tocqueville, Kronman said, greatly admired American democracy, but he also realized that it wasn’t perfect, that it has a tendency to “flatten out the distinction between what is really great and what is ordinary, and to convert greatness to celebrity.” Furthermore, American democracy encourages the “tyranny of the majority opinion,” a real danger to American democracy.

The antidote is “aristocratic sensibilities” in order to promote the “independent mindedness” that America has, but which is under increasing attack. While “aristocratic” is a word that often has a negative connotation in today’s society, Kronman said that is due to a misunderstanding of its meaning.

“We call them aristocratic because they are devoted to the ideal of excellence in culture, thought, and judgement, to the extent they are devoted to an aristocratic set of values, they run against the grain of the sensibility of the democracy at large,” he told The Fix.

One analogy Kronman used in his book to illustrate this point was the decision to do away with the “master” title at Yale University because some faculty and students said it reminded them of slavery:

The Pierson master who gave up his title could not possibly have thought that he might be confused with the owner of a Mississippi plantation. What really disturbed him, and his students, was not race but rank. It was the aristocratic implication, however slight, that men and women can be distinguished according to their success not in this or that particular endeavor—the study of computer science, for example, or Greek philosophy—but in the all-inclusive work of being human. This idea has been accepted by many cultures of the most varied sorts. It has been joined with other beliefs, some pernicious and others benign. But at the most basic level, it runs against the grain of America’s democratic civilization. It seems—it is—antidemocratic. Any institution that embraces the idea of aristocracy, even in the most modest and qualified terms, therefore puts itself at odds with our civilization as a whole.

In his interview, Kronman added: “Our colleges and universities have lost confidence in the value and the legitimacy of their own aristocratic ethos and have instead permitted themselves to be engulfed by a set of increasingly strident egalitarian demands for the dismantlement, for the leveling, for the extinction, of those old aristocratic values and distinctions.”

Historically, the purpose of a college education was for something far more significant than just preparing an individual for a career, Kronman said. Rather, it was meant to teach young minds how to be a more well-rounded person who has studied complex questions about human existence and society. The primary vehicle for this is the “liberal arts” curriculum that has been at the center of higher education for centuries, instructing students in the practices of philosophy and critical thinking using texts from great historical scholars, he said.

But today, the vast majority of students seek a path of least resistance and will usually opt against testing their minds by reading such works like Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics” or Plato’s “Republic,” and the fill-in-the-blank degree course requirements are mainly to blame.

But today, the vast majority of students seek a path of least resistance and will usually opt against testing their minds by reading such works like Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics” or Plato’s “Republic,” and the fill-in-the-blank degree course requirements are mainly to blame.

“If the choice is completely up to you, and you’re able to study whatever you wish, you will pick courses that either fit your vocational plans, whatever they may be, or fit your preconceptions of what is morally and politically valuable and important,” Kronman said. “You will take courses that will better help you figure out how to understand and implement the moral and political ideals you already have.”

“Some way must be found to put some meat back on the bones of the skeletal distributional requirements,” Kronman added.

When asked what role studying religion played in the study of ideas, Kronman — a self-described “American humanist” — said it is a “woeful ignorance” if a student hadn’t spent time studying the ideas and texts of the Abrahamic religions, namely Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

“It is important that a liberal arts program of the kind I have in mind…take with utmost seriousness the moral and spiritual claims of these same religious traditions,” he said.

“I really strongly believe that a rounded education ought to include a systematic introduction and exposure to these works and ideas, but not in the spirit of belief,” he said. “Rather in the spirit, the same spirit, of critical inquiry that ought to govern exposure to the great secular texts of moral, political and cultural thought.”

In his interview, he said he is not suggesting that some humans are less valuable than others.

“When it comes to politics and law, the principle of the equality of all human beings, regardless of their level of intellectual or moral or cultural development, seems to me fundamental and essential,” he said.

“… But to completely dismiss the notion that there are grades of excellence in the work of being human and that the point and purpose of an undergraduate education at a liberal arts institution is in part to help students develop the powers and capacities that advancement toward excellence requires, to give up on that seems to me a terrible loss, and not one that is required at all by the embrace of the principle of equality in political and legal matters.”

The veteran academic acknowledged that his “seniority” provides him with some level of protection and freedom from consequences that he may otherwise face for making this argument, but he added “I’ve also been in the habit for many years of speaking my mind and this is just another instance of that.”

“I don’t think that my book is in any way extreme,” Kronman told The Fix. “If it is received as such, that to me is a disturbing sign of how far out of kilter we are today in our colleges and universities.”

MORE: Journalist runs for Yale trustee to take on trigger warnings, mob justice

MAIN IMAGE: Jeremiah Poff

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.