Every bad experience reinforces this notion

Many moons ago, I edited several sections of a student newspaper at an evangelical Christian university. A few members of the pro-life club submitted an article arguing students should think twice about using the pill, because it can have abortifacient effects.

That was a debatable proposition, and not one that I particularly bought into. But they had cited sources that students could go look at and evaluate for themselves. It seemed a worthy enough subject for consideration. Since it didn’t fall under the subject matter of my sections, I passed it onto the appropriate editor and went about my business.

After publication, the pro-life clubbers again contacted me. They were quite upset. Their sources had been in footnotes, which of course papers don’t usually use. Standard practice is to take the relevant information from the footnotes and edit them back into the articles.

For instance, let’s say that I make a claim that is footnoted like so[1]:

[1] Guy, Some. “Book With Stuff in It.” Big Publishing, 1998.

When writing about that in an article for The College Fix, I might say:

As Some Guy argued in “Book With Stuff in It,” frogs don’t like raspberries.

That way if people read the claim in my article that frogs don’t like raspberries and disagree, they can see I am citing an authority for that statement.

It might be wrong, of course, and I may even be foolish for citing that particular source. However, readers can see I am not simply pulling it out of my proverbial ear.

In the case of this article, the standard practice of folding in footnote information was not observed. All of the footnotes were stripped out. None of the sources were cited in the final version.

Worse, it was turned into a point-counterpoint, with artwork. This artwork included sperm swimming toward a rosary. The editorial description referenced a Monty Python musical number by asking, “Is every sperm sacred?”

Was this amusing? Perhaps, in a sophomoric way, but that was not the point that the pro-life clubbers had been making, and it went against any notion of basic fairness in publishing.

So the clubbers approached me and asked, “What do we do about this?”

Fortunately, for them, I also edited the letters column of the paper.

“Carpet bomb me with letters,” I advised.

Over the next two issues, the paper ate a tremendous amount of crow. The pro-life clubbers letters all ran, as did letters on the other side of the issue.

Yet when, say, someone criticized the pro-lifers for not citing sources, those letters were followed by editorial notes admitting this was due to an error of the paper.

The embarrassment was so thorough that the paper eventually stopped sending me letters-to-the-editor to edit but kept paying me for editing that page. I didn’t protest because we were nearing the end of the year anyway, and the point had been made.

But perhaps not well enough made.

The paper was not independent of the university. Once a year, the student council picked the editor of the paper, and the school’s vice president of something-or-other had a veto.

I went up for editor of the paper for the next year, with a clips file that would break your foot if it fell on it. That is not an exaggeration. Print was still a thing back then and this was a huge file. Given about a five foot drop, your foot would have broken in a few places, unless you were wearing steel toed boots or something.

If you guessed that I lost out to the copy editor who had penned the counterpoint article and, at the very least, done a terrible job on the edits of the point article, well then you win something special. You are also probably a conservative.

(To be fair, the vice president eventually vetoed her. A less controversial candidate who was more closely connected with the council was made editor.)

At this point, conservatives, libertarians – anyone who doesn’t march in lock-step with ever-shifting elite opinion, really – are used to this sort of thing from the wider world of media.

We see stories throttled or pulled down on social media not because they are untrue but because they rub one of the cool kids with a STEM degree the wrong way.

We see polls constantly marshaled to “prove” the public thinks a certain way about certain candidates and issues, and thus have fewer reservations about flat out lying to pollsters.

We watch theoretically neutral institutions like the Associated Press take up a contentious issue like abortion and label one side “abortion rights supporters” and the other the team not “pro-life” as they describe themselves, but rather “anti-abortion.”

Since all human beings are said by various authorities, religious and secular, to be vested with rights, that amounts to taking a position on fetal life that is remarkably inconsistent with how normal, compassionate human beings treat women with baby bumps.

This is a real problem for folks trying to do honest journalism, regardless of their political perspectives. If a huge swath of people hold your profession in contempt, they are unlikely to talk to you, thus robbing you of their knowledge and point of view.

There are ways around this for diligent journalists, but every single bad experience with journalism makes it that much harder for us to get at the whole story.

I recently wrote the following to a source who had reluctantly talked to me, even though he generally despises the press: “I know you hate journalists. I hate us too. But thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts on this. It added a lot to the article.”

MORE: Petition against Catholic university’s pro-abortion club reaches 35,000 signatures

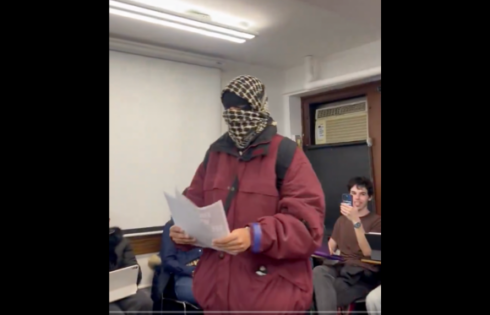

IMAGE: Wolf Pack for Life/Facebook

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.