ANALYSIS: Prominent feminist scholar argues white women can’t win within the confines of an antiracist worldview because they can’t escape their whiteness

A prominent feminist scholar has spelled out the Catch-22 for white women seeking to be antiracist: it’s impossible.

The problem has been dubbed “the impasse of whiteness” by Robyn Wiegman, professor of literature and women’s studies and formerly the Margaret Taylor Smith Director of Women’s Studies at Duke University.

Wiegman gave a talk at Princeton University March 28 titled “Who’s Afraid of Rachel Dolezal? Or, Feminism and the Impasse of Whiteness” to discuss the concept. The guest lecture was in-person only, but The College Fix obtained a copy of her essay on the subject.

According to the essay, it was written for a special issue of Duke University’s academic journal the South Atlantic Quarterly dedicated to “Feminism’s Bad Objects.” The special issue called for participating scholars to critically explore “objects, methods, figures, and thinkers that academic feminism has disavowed, jettisoned, or relegated to the category of our past-tense.”

In other words, the guest editors of South Atlantic Quarterly wanted scholars to pick some person or thing that contemporary feminist theory doesn’t like and explore it without judgment, to try to understand why contemporary feminist theory doesn’t like it without either condemning it or approving of it. The issue is as of yet unpublished.

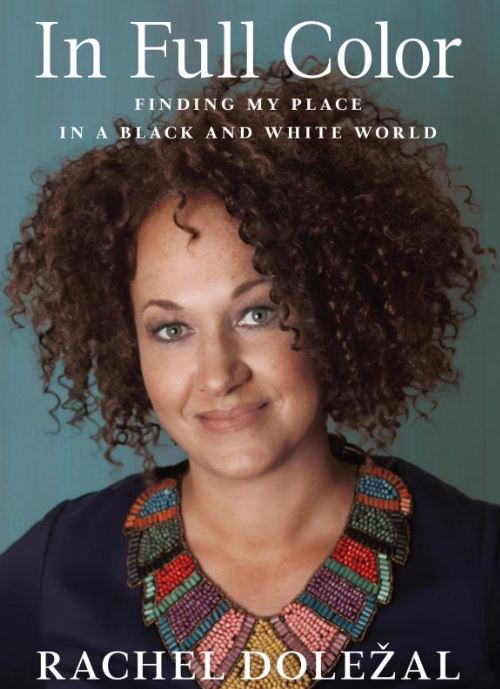

Wiegman’s target in the essay was Rachel Dolezal, a woman who has two white parents but insists that she feels black and, therefore, is black. Dolezal is a scholar and former NAACP chapter leader who identifies as “transracial” and has artificially darkened her skin and curled her hair in order to appear as a black person.

But Dolezal’s contemporaries have refused to accept her identity and have shunned and blackballed her. Wiegman, in her essay, argued that the reason why contemporary feminists dislike Dolezal so much is because Dolezal effectively escaped the white-woman trap by claiming to feel black.

Wiegman, who is white, links Dolezal to “the impasse of whiteness,” which is essentially a no-win situation created by antiracism in which modern intersectional feminism now apparently demands that “white feminism” be dismantled to allow “black feminism” to exist.

In “the impasse of whiteness,” white women can’t win within the confines of an antiracist worldview because they can’t escape their own intrinsic whiteness, according to Wiegman’s essay.

According to antiracism, whiteness is inherently oppressive and, by definition, thoroughly embedded in society in the form of structural racism or “anti-blackness.” White people have intrinsic privileges within this structural racism simply for having been born white. Therefore, “whiteness” is more than just white people existing. Rather, “whiteness” is the very oppression itself that is baked into every aspect of our society.

Antiracism also preaches that race is a social construct rather than a biogenetic reality, but that the impact of centuries of people prejudging other people by appearance or ancestry has made race “real” in terms of how people treat other people within our structurally racist society. In other words, race isn’t defined by how someone looks, but by the reactions elicited by others based upon how someone looks, and those reactions create and maintain structural racism.

Under this paradigm, the professor argued, white women’s “lived experiences” are seen as invalid by antiracism because everything they experience is colored by their privilege. As such, they are intellectually incapable of objectivity when analyzing their own experiences, and they are therefore emotionally incapable of feeling genuine sympathy for anyone who isn’t also white.

Further, since they cannot use their “lived experiences” to truly be conscious of their own privilege and the racism inherent in the system, they cannot really do anything to fix the problem. In short, a white woman who wants to be an ally in antiracism must constantly work to dismantle her own whiteness, but she cannot escape her whiteness altogether because the racism that gives her whiteness “privilege” is baked into the system, Wiegman wrote.

Therefore, the only way for white people to participate in antiracism is for them to agree with it utterly and feel neverending shame for having been born white. They have to accept that they are a symbol of the oppressive system, a symbol of “whiteness,” and are thus inherent supporters of the structurally racist status quo.

They have to suffer, and there is no way out of the suffering because there is no way to fully escape their whiteness. This entire situation is what Wiegman called “the impasse of whiteness,” a trap created  by antiracism in which white people – and, for feminism, white women – are not allowed to “fix” the problem of their own whiteness. They simply must live in it and stew in their own guilt over being born the wrong race.

by antiracism in which white people – and, for feminism, white women – are not allowed to “fix” the problem of their own whiteness. They simply must live in it and stew in their own guilt over being born the wrong race.

In addition, it is at least partially because of this trap that contemporary feminism is, according to Wiegman, turning away from a lot of feminism’s founders as part of a “white feminism” that challenges the patriarchy but fails to challenge structural racism and is thus simply not intersectional enough. Antiracism demands that whiteness be dismantled to allow blackness to exist.

Ultimately, Wiegman argued that by insisting that she never was “truly” white, Dolezal simultaneously claims that her lived experience is valid and that she doesn’t need to endure the shame and discomfort of being a white ally, and Wiegman suggests that is infuriating to antiracists because Dolezal refuses to stay in the box they’ve created for her.

In her essay, Wiegman briefly acknowledged but did not fully address the comparison that can be made between transgender people who state that they feel that they should have been born the opposite sex and Dolezal, who states that she feels that she should have been born a different race.

Apparently, comparisons between “transracialism” and “transgenderism” have been made but are taboo in contemporary feminism. She noted this but didn’t go into it or explain why.

Wiegman noted in the essay that she was trained in cultural studies and poststructural theory, which is to say that her training is in postmodernism and cultural Marxism, the philosophical sources of antiracist ideology. Since that is how she was “raised” academically, it stands to reason that while she pointed out flaws (she called them inconsistencies) in intersectional feminist thought, she generally uncritically accepted all of the assumptions of intersectionality, feminism, and antiracism at face value.

Until recently, Elisa Parrett was a college professor of English, but she has recently left academia in the wake of too much “wokeness.” She is now a writer and editor for a comedy news show on YouTube and Locals called America Uncovered. She is also a wife and a mother, and, in what little spare time she has, occasionally a fiction writer.

IMAGE: Inside, Amazon screenshot of bookcover; YouTube screenshot

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.