China is getting antsy that its universities are becoming too Western.

“Separate statements by Peking University in Beijing, Fudan University in Shanghai and Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou were published Sunday under the headline ‘How to carry out ideological work at universities under new historical conditions’ in the party journal Qiushi, which means ‘seeking truth,’” The New York Times reported Tuesday.

The schools especially want to protect and defend Chinese Communist values by creating a “positive online environment,” which includes monitoring opinion online, the Times said.

The funny thing is, China’s state action may be nothing more than a Hyperlapse recording of broader global trends.

Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, argues in his short new book, Freedom From Speech, that dwindling respect for free speech on campus and in America is just one example of a much more worrisome trend:

Greg Lukianoff, president of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, argues in his short new book, Freedom From Speech, that dwindling respect for free speech on campus and in America is just one example of a much more worrisome trend:

I do not think – nor have I ever thought – that blame for the erosion of support for the cultural value of freedom of speech can be laid entirely on the ivory tower. The “It’s all academia’s fault” argument does not adequately explain why freedom of speech seems to be on the decline across the globe, even in countries that claim to value civil and political rights.

That includes the U.K. – which has jailed people for “grossly offensive” comments on social media – and Iceland, India and Turkey all have problems with social media too. (Lukianoff also notes student unions in the U.K. banned Robin Thicke’s raunchy song “Blurred Lines.”)

‘We Can Always Learn Something From Listening to the Other Side’

In America specifically, Lukianoff traces growing intolerance for different viewpoints to “problems of comfort” in the peaceful modern age. Increased mobility, for example, lets Americans “congregate within counties, towns, and even neighborhoods populated by politically like-minded people.” There’s also a growing sense that hard issues – which used to be resolved with war – can be dealt with “while remaining universally inoffensive,” a hopelessly naive idea.

Much more than fighting “liberal groupthink” or “political correctness,” what’s needed is a robust defense of what might be simply termed listening:

These values incorporate healthy intellectual habits, such as giving the other side a fair hearing, reserving judgment, tolerating opinions that offend or anger us, believing that everyone is entitled to his or her own opinion, and recognizing that even people whose points of view we find repugnant might be (at least partially) right. At the heart of these values is epistemic humility – a fancy way of saying that we must always keep in mind that we could be wrong or, at least, that we can always learn something from listening to the other side.

The Tyranny of the ‘Care Ethic’

While Lukianoff asks readers, many of whom are likely to be conservative, to welcome liberals who value free inquiry and debate as allies, he takes aim at a likely root cause of the problem: “empathy.”

While Lukianoff asks readers, many of whom are likely to be conservative, to welcome liberals who value free inquiry and debate as allies, he takes aim at a likely root cause of the problem: “empathy.”

American progressives tend to evaluate morality solely under the “care ethic” – whether a proposed action “demonstrates care for the well-being or feelings of others,” particularly “victims.” That means they are more sympathetic to attempts at shielding “vulnerable” views from challenge, Lukianoff says.

The result on campus is that students, far from being warned about “confirmation bias,” are being taught to have “a sense of entitlement to an environment in which their beliefs are not contradicted (at least not too harshly).”

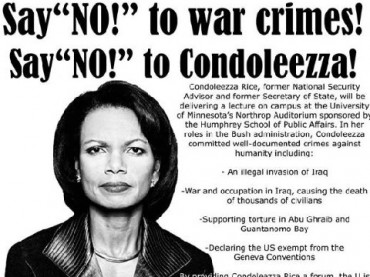

Freedom From Speech focuses on two key areas of concern just from the past year for groups like Lukianoff’s: “disinvitation season” (commencement speakers who are booted or bow out after protests) and trigger warnings.

In the past 15 years, students or faculty have a 43 percent success rate in driving away commencement speakers, according to FIRE’s tally, Lukianoff says. And it’s ramping up – more than half of the attempts and “successful” protests have happened since 2009. This is all the more remarkable, he says, considering how few conservatives are invited to give speeches in the first place.

From PTSD to ‘Classism’ Warnings

The spread of trigger warnings “may have even darker implications” for open discourse, Lukianoff says. They started on Internet forums for traumatized people, especially rape victims, he says, citing a New Republic story from March, but “spread through feminist forums like wildfire”:

From there, the phenomenon mushroomed into a staggeringly broad advisory system that, as [author Jenny] Jarvie explained, now covers “topics as diverse as sex, pregnancy, addiction, bullying, suicide, sizeism, ableism, homophobia, trans- phobia, slut shaming, victim-blaming, alcohol, blood, insects, small holes, and animals in wigs.”

Oberlin College’s trigger warning policy, suggested but not mandated for faculty, was intended to protect sexual-assault victims with PTSD, but it mentioned a long list of “isms” that have no relation to clinical PTSD triggers, among them “classism.” One professor told the New York Times it would particularly endanger faculty without tenure, and another group of faculty wrote in Inside Higher Ed that actual PTSD sufferers need professional help, not classroom coddling.

The University of California-Santa Barbara gets two mentions from Lukianoff.

The University of California-Santa Barbara gets two mentions from Lukianoff.

The co-author of a trigger-warning resolution there said her inspiration was a “sickening” depiction of rape in a film for class – which was not an actual “trigger” for her. A pregnant professor who assaulted a pro-life student for her graphic aborted-fetus sign justified her attack by claiming not only her, but other students nearby, were “triggered.” Yet in a video of the incident, the professor “seems positively gleeful” ripping away the student’s sign.

Comedians and Satirists As a Weapon

So what’s the big deal, trigger-warning advocates say? Lukianoff says:

For those who believe that Haidt’s care ethic is paramount and that offering such warnings is simply a means of showing empathy, conscientiousness, and care, the widespread criticism of the practice is probably fairly mystifying. To those who value intellectual freedom, however, trigger warnings are yet another manifestation of the attitude that society must protect every individual from emotionally difficult speech.

And boy, is that a “perilously slick” slope. Campus censorship has been applied to everything from “quoting popular television shows to faintly implying criticism of a university’s hockey coach,” Lukianoff says, and he wants allies in the fight:

Comedians and satirists may also join the pushback against the infinite care ethic; after all, it is blazingly clear that politically correct censorship and comedy are natural enemies.

That has long been my hope too. But the troubling trends identified by Lukianoff have taken place in the middle of perhaps the greatest satire of political correctness of the past two decades: Comedy Central’s South Park.

If “problems of comfort” are the seed bed for The Rule of Empathy’s growth, perhaps the latest tactic taken by Lukianoff’s group, briefly addressed in the book, is the stronger herbicide: litigation.

Greg Piper is an assistant editor at The College Fix. (@GregPiper)

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

IMAGES: Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, online video screenshot

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.