OPINION

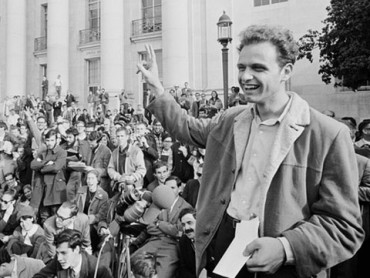

The University of California-Berkeley is commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement this fall, and our chancellor has made an unusual contribution to its legacy: arguing that free speech can “undermine a community’s foundation.”

Nicholas Dirks, himself an historian, said in a campus-wide email last week that it was important to recognize “the broader social context required in order for free speech to thrive.” He argued for the campus community to determine when free speech goes too far: “Specifically, we can only exercise our right to free speech insofar as we feel safe and respected in doing so, and this in turn requires that people treat each other with civility.”

Needless to say, this is a curious interpretation of the animating principle of the movement that cemented Berkeley’s place in the history books. Berkeley is the university remembered for its student dissent, civility be damned.

Not only do we have the Free Speech Monument circle on Sproul Plaza, the school’s main area—where students coordinated sit-ins to prevent police from arresting a classmate on October 1, 1964—but we also have the FSM Café at the Main Library. Courses in history, my field of study, and other disciplines consistently cover the Free Speech Movement in different contexts.

This semester alone, there are about a dozen courses that I know of on the Free Speech Movement and other student movements in the 1960s, one of which I’m helping facilitate.

The Free Speech Movement is one of Berkeley’s proudest stakes in history.

One history professor, who “was among those targeted” in the blacklisting efforts of the school and FBI, even wrote in a volume on the movement that “the legacy of the FSM… gave as much to this campus as any of its distinguished Nobel laureates, financial benefactors, or athletic coaches.”

Graded Down for Not Demonizing ‘the Top 1 Percent’

One place where I agree with Dirks, however, is his contention that “[f]or free speech to have meaning it must not just be tolerated, it must also be heard, listened to, engaged and debated.”

From my experience at Berkeley, this legacy of the Free Speech Movement has not been fulfilled.

Yes, I do appreciate the significance of having such a lively hub of student activity at Sproul Plaza as well as the critical conversations I regularly overhear at the FSM Café. Just this weekend, I overheard a few students criticizing our Gender and Women’s Studies as white women’s studies.

It is this critical and active student community that makes Berkeley one of the top universities in the world. It was also this notion of “critical theory,” Jeremi Suri argues, that “provided a vocabulary for diverse protests” in the 1960s.

Yet many opinions in Berkeley classrooms are constantly discouraged, sometimes with academic threats. Just last year, student representatives banned the term “illegal immigrant” from “campus discourse,” apparently unaware that banning words is the antithesis of free speech.

A graduate student instructor radically lowered my grade in a geography course because I “failed” to appeal to the instructor’s animosity toward “the top 1 percent.”

Ronald Reagan is a particular sore spot. I sensed the general displeasure of my classmates with the Reagan administration when going over the 1980s in a U.S. history course last summer. “Well, I think we need to look beyond his role in quelling the 1960s Berkeley rebellions,” I said then.

And in my last opinion column for the Daily Californian student newspaper in memory of Reagan’s passing 10 years earlier, I received a handful of close-minded comments unwilling to actually understand my argument.

It is this kind of eggshell-walking that Dirks pushes for in his email in order “to maintain that delicate balance.” The result is that some opinions are essentially left out, preventing meaningful debates in the classroom from which we can all learn.

Chancellor, if we as historians, and as Berkeley community members, are to truly “honor the ideal of Free Speech,” as you say, then the intellectual community that is Berkeley needs to be more open to all critical viewpoints in the classroom.

“As we honor this point in our history,” we must also truly honor free speech.

College Fix contributor Kevin Reyes is a student at the University of California-Berkeley.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

IMAGE: Sam Churchill/Flickr

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.