Few autistic students go public with speech code punishments

Portland State University considers the slang term “snowflake” a potential form of “harassment and intimation.”

The public university justified a professor’s decision to ban Lindy Treece, an autistic student, from the weekly class for using such “derogatory language” in relation to the presidential election.

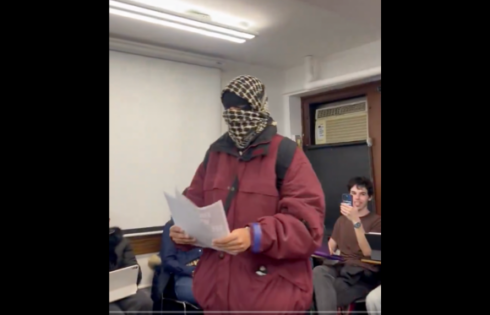

The professor told Treece (above) she would only be allowed to rejoin the class if she agreed not to use unspecified offensive language going forward, the graduate student told The College Fix in an email.

Treece said PSU backed down after she threatened to sue, and she attended the following week’s session. She also sought help from the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, which publicized the incident.

MORE: Court overrules college that punished autistic student for asking for fist bump

Adam Goldstein, senior research counsel to the president at FIRE, told The Fix he and others at FIRE have worked on cases similar to Treece’s where the “neurodivergent” student didn’t want to go public. This is why FIRE wanted to write about Treece’s situation.

While people on the autism spectrum can more easily follow a speech code that simply bans a list of words, “college speech restraints are attempting to punish speech that might make someone feel bad, or unwelcome, or emotionally unsafe,” Goldstein said.

A university spokesperson did not directly answer Fix questions about Treece’s incident, including what discretion professors have to decide what counts as prohibited “derogatory language” in classroom discussions.

“The robust debate of ideas is the underpinning of a liberal arts education at a public university,” Christina Williams, director of media and public relations, wrote in an email. “At the same time, we are responsible for keeping our campus safe from harassment and intimidation, and we ask that students express views in ways that respect others.”

Professor allegedly told class they’d talk about her behind her back

Treece’s social-work class was discussing the election over Zoom on Election Day when she commented: “I’m going to accept the results of the election no matter what because I’m not a snowflake.”

The professor immediately turned off Treece’s camera and microphone and emailed her after class, according to FIRE. Treece must “agree to not use derogatory language (including the term ‘snowflake’) in class moving forward” if she wants to continue in the class, the professor wrote.

Treece told The Fix she refused to accept the professor’s terms because “derogatory language” was subject to the professor’s opinion.

“[T]he think-before-you-speak advice is essentially a logical fallacy for us autistic people… we are unaware of how others will be impacted until it happens,” she wrote in her response to the professor.

The professor was aware of Treece’s autism because they had a discussion about it a week before the incident. The student explained how her condition “makes the classroom environment difficult,” Treece told The Fix, and she “recounted instances in the program when I had offended the class accidentally.” (She did not explain how she knew she had offended her peers in previous classes.)

MORE: The large-scale weaponization of Title IX against students with autism

Treece said she didn’t invoke the Americans with Disabilities Act or other law on disability in response to the incident.

“The problem with invoking any disability law in regards to autism is that you cannot prove that autism definitively caused a certain behavior,” she said. “I do not expect to never be held accountable for the impacts I have on others just because I have autism.”

She decided to pursue legal action against the university because the following day, the professor told the class “she would be reserving class time to talk about me and my impacts without me present,” Treece said.

The director of student affairs didn’t respond to Treece and the director of her master’s program only offered to meet her after she started talking to law firm Freedom X, she said.

The firm, which has represented students in California and Washington, took on Treece as a pro bono client. “They wrote a letter to the School of Social Work threatening a lawsuit if I was not allowed back in class without conditions,” she said. “The Dean then mandated that the instructor allow me to attend class.”

Expected to comply with ‘free-floating, ever-expanding list of concepts’

“Students on the spectrum disproportionately struggle with speech codes,” Greg Lukianoff, president and CEO of FIRE, wrote in the group’s blog post.

Speech codes are typically based on societal norms for upper-class Americans, he said. Neurodivergent students already have trouble with social cues so it can be especially hard for them to understand these norms.

FIRE has seen a surprising number of autistic students get in trouble at universities, Lukianoff said.

Any speech code that isn’t simply a list of banned words is a “free-floating, ever-expanding list of concepts that all hinge on being able to anticipate how someone else feels about something,” Goldstein told The Fix.

“An autistic student genuinely may not be able to predict when someone will feel bad, or even realize if someone reacted negatively to what was just said,” but such students often don’t speak up to publicly defend themselves against accusations, Goldstein said.

They might not want to share their spectrum status publicly or provoke “social media mobs” to come after them for their insensitive speech. When schools don’t know in advance that the student is on the spectrum, sometimes talking to the school can resolve the issue, he said.

MORE: Appeals court reinstates speech code suit against University of Texas

“That’s what made Lindy’s situation unusual: she’s open about her autism, most people aren’t offended by someone saying she’s not a snowflake, and the professor clearly knew Lindy was autistic,” Goldstein said. “It’s rare that all of those things are clearly true up front.”

FIRE did not have any role in the outcome of Treece’s case, Goldstein said. (Treece said she was hoping for “advice, representation, and/or publicity” by contacting FIRE, but that Freedom X was already working with her.)

The Fix asked Williams, the university spokesperson, if PSU banned “derogatory language” in the speech code and what discretion professors have to identify it; if professors can make fair judgments on “derogatory language” without leading to viewpoint discrimination; and how the university protects neurodiverse students against potential discrimination caused by its own policies.

Williams invoked the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act to decline to comment, even though Treece has publicly spoken about her claims under her own name.

The spokesperson said the university “respects and supports free speech and academic freedom,” quoting from its “Free Speech Guide.”

MORE: Student journalist sues ASU for removal over Jacob Blake tweet

IMAGE: Lindy Treece/Facebook

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.