‘Latinx’ failed because it reflects the progressive ideology of a minority, not the needs or self-understanding of most Latinos

American universities have adopted “Latinx” as a new way to describe people of Latin American descent without reference to sex or gender – but Latino people dismiss the descriptor, if they’ve even heard of it.

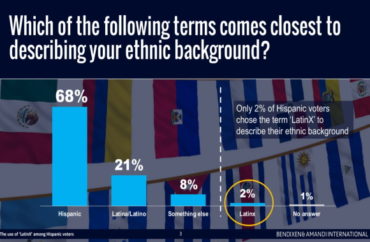

A recent poll found that only 2 percent of voters said the term Latinx “comes closest to describing [their] ethnic background.”

Thirty percent of the voters said they’d be “less likely” to support a politician or political organization that used the term. Instead, 60 percent of voters endorsed “Hispanic.”

“The use of LatinX among Hispanic voters,” the November 2021 poll, was funded by Bendixen and Amandi International, a Miami-based Democratic firm, and relied on interviews with 800 registered voters of Hispanic and Latino origin residing in the United States.

Even more, a 2020 report from the Pew Research Center found that just one in four Latinos had even heard of Latinx.

The term’s origin date is disputed.

According to linguist John McWhorter in The Atlantic, Latinx took hold in 2014 as a way to refer to Latino Americans, a gender-neutral alternative to Latina and Latino. “It has been celebrated by intellectuals, journalists, and university officials,” McWhorter wrote.

Latinx caught on in academia. In Latinx: A Brief Handbook, a 2016 guide written for the Princeton University LGBT center, then-undergraduate author Arlene Gamio said that “the term is used primarily in the United States by college students, academics, and social media users.”

Academics and universities seem to have embraced the term because it reflects a progressive dogma that differences between men and women are artificial and can be rejected by people who don’t want them.

But the term “Latinx” is an artifact of progressive culture, not Latino culture. Despite the success of “Latinx” on campus, the Latino community – including most students – have not taken it up.

“Hispanic” refers to individuals who speak Spanish and often descend from Spanish-speaking populations, while “Latin” or “Latino/a” refers to people of Latin American origin or ancestry, according to Hispanic Network. The two groups are not identical, but the overlap is so large that the terms are often used interchangeably.

Hispanic and Latin students comprise a larger percentage of college students than at any other time in American history. A November 2021 report by the Education Data Initiative states that Hispanic and Latino students make up 19.5 percent of the American undergraduate population – a 441.7 percent increase from 1976.

U.S. Representative Ruben Gallego, a Democrat from Arizona, the son of Hispanic immigrants, and Vice Chair of the LGBT Equality Caucus, stated in December 2021 that he had forbidden his staff from officially using the term.

To be clear my office is not allowed to use “Latinx” in official communications.

When Latino politicos use the term it is largely to appease white rich progressives who think that is the term we use. It is a vicious circle of confirmation bias. https://t.co/kMty6q7UQn— Ruben Gallego (@RubenGallego) December 6, 2021

“When Latino politicos use the term it is largely to appease white rich progressives who think that is the term we use,” Gallego tweeted. “It is a vicious circle of confirmation bias.”

Days later, Domingo García, president of the League of United Latin American Citizens, the oldest American Latino civil rights organization, told his staff to ditch the term.

While Latinx may address the concerns of a minority concerned with gender bias, its neglect suggests that the majority may not perceive this as a problem.

Latinx “dispenses with the problem of prioritizing male or female by negating that binary,” said Ed Morales in his 2019 book “Latinx: The New Force in American Politics and Culture.”

However the question remains whether most people of Latin descent think the collective noun Latino implicitly favors men over women, or whether male and female is a binary that most Spanish speakers need or want to eliminate.

In the Atlantic piece, McWhorter noted that words “stick” when they respond to real problems. On this measure, McWhorter said, Latinx has failed:

Latinx, too, purports to solve a problem: that of implied gender. True, gender marking in language can affect thought. But that issue is largely discussed among the intelligentsia. If you ask the proverbial person on the street, you’ll find no gnawing concern about the bias encoded in gendered word endings.

Not only does Latinx fail to respond to any widely shared need, it imposes an alien standard of gender neutrality, a “nonbinary” ideal for a complex culture replete with varied and vibrant manifestations of male and female.

NBC News quotes Motecuzoma Sanchez, a Latino political activist and community organizer, who “sees ‘Latino’ and ‘Latina’ as describing the different roles men and women have historically adopted.”

To throw out these terms “is to disrespect the entire culture as well as our brothers, fathers who have fought hard to be respected as men,” Sanchez said.

In adapting Latino and Latina to Latinx, advocates of the term also betray an ignorance of Latin languages, in which the gender of nouns is a linguistic construct distinct from the newer idea of gender as male and female.

In other words, just because a language has masculine and feminine nouns and the gender-inclusive term (e.g. “Latino”) is the same as the male term, it doesn’t follow that the language is implicitly valuing men and women in a certain way, or claiming that one is better than the other. The gender division is just how the language works.

In a 2015 op-ed for the Swarthmore Phoenix, the independent newspaper of Swarthmore College, students Gilbert Guerra and Gilbert Orbea said that gender in the latter sense is intrinsic to the Spanish language:

Spanish is a gendered language. If you take the gender out of every word, you are no longer speaking Spanish. If you advocate for the erasure of gender in Spanish, you then are advocating for the erasure of Spanish.

Swarthmore students Guerra and Orbea call this “linguistic imperialism”: “the forcing of U.S. ideals upon a language in a way that does not grammatically or orally correspond with it.”

“The term [Latinx] is virtually nonexistent in any Spanish-speaking country,” they wrote. Even more, Guerra and Orbea stated:

It may surprise you to learn that a gender-neutral term to describe the Latin-American community already exists in Spanish. Ready for it? Here it is: Latino. Gender in Spanish and gender in English are two different things.

Popular opinion has proved a powerful bulwark against the forces of progressive Newspeak that would remake Latin culture and language in its own gender-neutral image.

MORE: Why terms like ‘Latinx’ don’t stick

IMAGE: Politico

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.