‘A shameless, unconstitutional scheme designed to skirt judicial review’

An easy way for federal agencies to get what they want, regardless of the laws on the books, is to issue “guidance” purporting to explain the law.

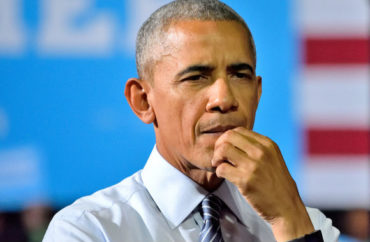

It’s how the Obama administration forced colleges to drastically lower their standards for sexual assault investigations and adjudications starting in 2011.

The threat of federal investigation, possible defunding – and perhaps most importantly, public shaming – was enough to convince colleges to make it easier to find accused students guilty. They banned cross-examination, lowered evidence standards and imposed double jeopardy on exonerated students.

Was this authorized by law or regulation? Of course not, and a lawsuit targeting the “Dear Colleague” guidance was proceeding when the Trump administration rescinded its predecessor’s guidance.

The administration is going even further with a pair of executive orders issued Wednesday that would bar federal agencies from issuing “substantive guidance” – in other words, new rules outside a formal rulemaking.

The first order criticizes commonplace agency practices of evading the notice-and-comment provisions in the Administrative Procedure Act by issuing substantive guidance:

Even when accompanied by a disclaimer that it is non-binding [the Obama administration’s repeated defense of its “Dear Colleague” guidance], a guidance document issued by an agency may carry the implicit threat of enforcement action if the regulated public does not comply. Moreover, the public frequently has insufficient notice of guidance documents, which are not always published in the Federal Register or distributed to all regulated parties.

The order instructs federal agencies to “treat guidance documents as non-binding both in law and in practice,” include public input in formulating guidance, and make the documents “readily available to the public”:

Agencies may impose legally binding requirements on the public only through regulations and on parties on a case-by-case basis through adjudications, and only after appropriate process, except as authorized by law or as incorporated into a contract.

They have 120 days following the “implementing memorandum” from the Office of Management and Budget to review their own guidance documents and rescind those that they determine “should no longer be in effect.” If it wants guidance to remain in effect, an agency must publish the document in a “single, searchable, indexed database” on its website.

The second order bars federal agencies from pursuing “a civil administrative enforcement action or adjudication absent prior public notice of both the enforcing agency’s jurisdiction over particular conduct and the legal standards applicable to that conduct.”

It notes that the Freedom of Information Act amended the Administrative Procedure Act to better protect Americans from “the inherently arbitrary nature of unpublished ad hoc determinations”:

The Freedom of Information Act also generally prohibits an agency from adversely affecting a person with a rule or policy that is not so published, except to the extent that the person has actual and timely notice of the terms of the rule or policy.

Unfortunately, departments and agencies (agencies) in the executive branch have not always complied with these requirements. In addition, some agency practices with respect to enforcement actions and adjudications undermine the APA’s goals of promoting accountability and ensuring fairness.

The order binds agencies to “apply only standards of conduct that have been publicly stated in a manner that would not cause unfair surprise” to a target of enforcement, adjudication or other forms of “determination” that have “legal consequence.”

It even requires them to publish any document that they intend to enforce “arising out of litigation (other than a published opinion of an adjudicator), such as a brief, a consent decree, or a settlement agreement.” This means agencies can’t spring new rules out of thin air on parties that weren’t subject to the litigation.

MORE: Accused student sues Department of Ed to end ‘unlawful’ investigations

President @realDonaldTrump just signed two executive orders aimed at restoring transparency and accountability to government bureaucracy. pic.twitter.com/HaIrySTHFP

— The White House 45 Archived (@WhiteHouse45) October 9, 2019

‘Don Vito Corleone would call this an offer a regulated party can’t refuse’

Michael DeGrandis, senior litigation counsel at the New Civil Liberties Alliance, explains the orders and their context at Reason today:

Guidance has been responsible for revoking permits to conduct business, barring Americans from working in their chosen occupations, prohibiting taxpayers from taking deductions, levying post-conviction penalties for crimes, and seizing property, without statutory or constitutional authority and without due process. Think of guidance as an off-the-books way for the government to ignore commonly held understandings of fairness. It’s a shameless, unconstitutional scheme designed to skirt judicial review, avoid public scrutiny, and evade accountability.

The simple truth is that agencies have too many incentives to issue guidance, he explains. “[I]t’s easier, faster, and cheaper than substantive rulemaking” and takes advantage of the fact that “courts don’t typically view guidance as final agency action,” meaning it can’t be reviewed in court:

For instance, a common agency tactic is to issue a warning letter to a regulated party, threatening enforcement [exactly how Obama’s “Dear Colleague” followups worked]. Though the regulated party has little choice but to comply with the agency’s demands, courts will not intervene because the letter itself does not establish sufficiently concrete legal consequences, as it is “merely” a notice.

Don Vito Corleone would call this an offer a regulated party can’t refuse. Agencies call it guidance.

Grandis celebrates the orders for the “revolutionary change” of turning posted guidance into “final agency action,” making it reviewable by the courts: “By specifying straightforward conditions for issuing and enforcing guidance, the Trump administration has increased the cost to agencies for issuing guidance.”

Read the orders and Grandis analysis.

MORE: Feds stop ordering colleges to judge students by low evidence standard

IMAGE: Evan El-Amin/Shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.