‘Panic Attack’ by Robby Soave

Are you an intersectional activist hoping to accomplish your limitless agenda, concurrently eradicating everything from whiteness and microaggressions to rape culture and capitalism with equal fervor and perfectly woke terminology?

Consider hiring Robby Soave as your consultant, as long as you can make one small compromise: drop intersectionality as your framework.

The Reason editor’s first book, “Panic Attack,” is a broadly sympathetic tour of radical, youth-led activism that exploded with the election of Donald Trump but has academic roots going back 50 years.

Soave could have just elaborated on his last few years of writing on the intersection (ahem) of campus activism, call-out culture and what free-speech advocate Greg Lukianoff calls “epistemic humility,” and made an important contribution to the layman’s field of tolerance and pluralism.

But he also sprinkles in first-person interviews with casual and professional activists (largely in their 20s) that he’s met in the course of his reporting, providing insights that readers are unlikely to glean from the activists’ own exhausting, jargon-heavy Medium posts.

Some of these interludes bring Soave into contact with people who do not want to talk to any media that are not from their own ranks. One intersectional feminist, for example, tells him “no means no” after he persists in seeking an interview.

But many others make a good-faith effort to educate him, breaking one of the cardinal rules of intersectionality: It’s not the job of the marginalized to educate you on their marginalization.

Though the most obvious audience for this 281-page work overlaps with the readership of Reason or The College Fix, where Soave previously served as an editor, it’s better directed at young people who are still developing their political and cultural identities. Soave himself is not far removed from their ranks: Forbes named him to its 30 under 30 list for “law and policy” in 2016.

And while he makes regular appearances on conservative media such as Fox News, Soave emphasizes that he wants to steer these young activists clear of the dead ends in their advocacy. They need a sense of history, of their forebears who succeeded in changing both culture and law.

Unfortunately for them – but fortunately for conservatives who want to see these easily triggered, endlessly intolerant Che clones crash and burn – many activists in “Panic Attack” tell Soave they have no interest in the lesson.

‘Almost hysterically opposed to building bridges’

The book assigns chapters to each member of the intersectional coalition, from Antifa and Black Lives Matter activists to fourth-wave feminists, gender-theory warriors and democratic socialists.

There’s also a sprinkling of climate-change and gun-control advocates. Conservatives, be warned: Turning Point USA and other conservative youth organizations are covered as well, and the book concludes with Richard Spencer and the alt-right.

But it’s important to first understand what intersectionality entails and how it went mainstream around the middle of this decade.

To be intersectional is to recognize and “stack” oppressions on top of each other: an obese black queer woman such as writer Roxane Gay has four oppressions “greater than the sum of their parts,” for example. The theory’s main popularizer, Kimberle Crenshaw, started with race and gender, but new oppressions continue to be added.

The more oppressions to stack, the greater moral authority, yet as Soave notes, there’s no obvious road map for “adjudicating competing claims of identity-based oppression.” The result is a reverse Jenga tower, closer to collapse with every new oppression piled on.

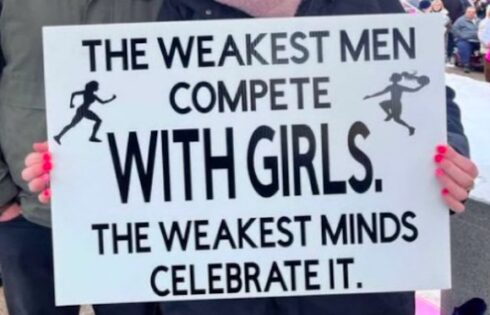

The framework is “fundamentally unlike the fondly remembered activist movements of decades past,” whose ends were radical but whose means were pragmatic, Soave says. Today’s intersectional activists “seem almost hysterically opposed to building bridges with potential allies” and want revenge on people who largely agree with them: They are “radically exclusionary” and skeptical of “open debate.” (One major exception he documents: Parkland shooting activists, who have shown unusual success in their anti-gun crusade in less than 18 months.)

The Zillennials – Soave’s term for millennials and their successor, Generation Z – grew up in an environment that sowed the seeds for this framework.

The child kidnapping panic of the 1980s encouraged parents to never let children out of their sight, even as they became adults, and draconian laws reinforced this practice. Zero-tolerance school disciplinary measures followed the Columbine shootings, even as school-related violence remained extremely rare.

It’s no wonder that “safety paranoia” has bled into the next generation of activists, who see language itself as perpetuating physical violence.

Soave speculates that one of the common word choices among race activists – referring to black people as “black bodies” – is popular because it reinforces their belief that emotional harms are also physical harms.

But he also astutely notes that the use of such jargon is an easy way to virtue signal. “Anti-whiteness is a performance – a social signaling device” – and the performance is often directed at the liberals who supposedly practice “superficial racial tolerance.” This explains the cries of “white supremacy” when an ACLU official tried to explain why left-wing student activists need the First Amendment at the College of William & Mary in 2017.

Yet the older cohort among the Zillennials seems more measured in their pronouncements. Soave notes the oldest among his interview subjects at one rally – a 28-year-old woman – was the only one to recognize that “hate speech” is constitutional. The rest believed it was already illegal, and one went so far as to say that “threatening identity” is unconstitutional.

Privileged white liberals who refuse to portray different identities

For a generation too young to remember the September 11 terrorist attacks, Trump’s election was “their 9/11,” a 26-year-old female Muslim activist tells Soave. Bloated by administrative offices and programs, their colleges canceled classes in the days following the election.

Yet years later, colleges continue promoting the message that the average student is crippled by mental health issues. Soave observed on a visit to Arizona State University – one of the better for free-speech protections – that the campus was littered with various posters advertising mental health services. College has become “sort of group therapy,” and students list their (often self-diagnosed) mental illnesses as a badge of honor.

These cultural practices are easy to laugh at from a distance, but Soave emphasizes the consequences faced by those who fail to perfectly navigate the infinitely fragile egos of students.

Perhaps the most depressing anecdote in the entire book takes up several pages. It involves “Helen,” a theater instructor at a Northeastern liberal arts college (some of the least tolerant places in America) whose crybully students nearly drove her out of teaching.

They were “incredibly privileged, mostly white” and “perpetually offended,” refusing to take on roles and insisting the material was too traumatizing to portray. (Helen used to teach Iraq war veterans, who never complained.)

A group of able-bodied students “ambushed” Helen after she assigned a student to portray a disabled character. Another accused her of “retraumatizing” sexual assault victims after Helen assigned her to portray a husband who pushes his wife out of bed, and complained that she was “forced to play a lesbian” even though she was an out-and-proud lesbian.

Her students made constant demands for out-of-class validation, accused her of invalidating them by giving them constructive criticism, and complained that she asked them to portray identities other than their own. The college administration repeatedly trained faculty to coddle these students rather than subject them to uncomfortable learning (the subject of another worthwhile recent book by a young writer).

There’s no way this generation of activists could have prompted the widespread decriminalization of marijuana or legalized gay marriage, “in some sense the last non-intersectionalist leftist cause,” as Soave notes. Intersectionality requires a secular form of perfection, as Soave concludes:

It’s not enough to share the intersectional progressive’s goals relating to a specific issue: one must also support their tactics, speak their language intuitively, defer to the wisdom of the oppressed without either speaking on their behalf or expecting them to speak for themselves, and commit to every other interrelated cause.

Look what arrived in the mail! Reminder, you can pre-order your regular sized copy here https://t.co/opmTjSAzjt pic.twitter.com/2wfhD0EGEN

— Robby Soave (@robbysoave) May 6, 2019

The black female law student who defended George Wallace

Recent history is not kind to the approach of the intersectionalists. Every serious scholar of civil-rights activism notes that it depended on free-speech arguments, and Soave emphasizes it to his potentially young and malleable readers.

The speech suppressionists of the 1960s were (also!) university administrators as well as law-and-order figures such as Richard Nixon, who correctly predicted that his policies would become more popular when “leftists are punching people in the streets,” as Antifa does today.

Soave reminds readers that University of California-Berkeley students – including avowed communists – invited an American Nazi to speak on campus and even dressed up as Nazis to promote the event in 1964. Mario Savio became their leader: “He did not favor free speech just for the safe, or the innocent, or the uncontroversial.”

In stark contrast, Berkeley progressives threatened to bring campus to a screeching halt when gay conservative provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos promised to return to campus in fall 2017. Soave observed that they played right into the hands of conservative student groups, who wanted to prove that “the campus left was just as censorious, violent, and destructive as advertised.” The ironic result: the militarization of campus to prevent Antifa violence.

Less known than Berkeley’s free-speech movement was the role a black female law student played in getting George Wallace – yes, the segregationist governor – to speak at Yale.

The administration tried to stop Yale’s Political Union from inviting him, but received a rebuke from Pauli Murray, who said Wallace had the same constitutional rights as her own civil rights activists. In comments that are just as prescient today, she told Provost Kingman Brewster that the “possibility of violence” does not justify the suppression of constitutional rights.

Soave urges young activists to realize how they functionally hand a megaphone to deeply unsympathetic figures when they try to shut down or intimidate speakers, noting that British fascists gained thousands of new followers in the 1930s after a celebrated anti-fascist riot in London.

He attended a (ticketed) College Republicans event with conspiracy theorist Mike Cernovich, who was not persuasive, but Soave encountered 100-plus protesters as he exited. They made ludicrous claims, including that Columbia is the “most conservative institution” in America, and some later threatened the Columbia student and former College Fix writer Toni Airaksinen.

Sometimes it’s only the supposedly marginalized themselves – shown by surveys to be far less woke than their self-appointed defenders, as Soave notes – who can quiet a hostile audience.

Soave attended an event with libertarian social scientist Charles Murray at the University of Michigan that was nearly shut down by student activists. One thing lowered the temperature: A Muslim man stood up and demanded quiet so he could hear Murray’s arguments.

One of the disrupters later told Soave (over pizza in a basement, of course) that potential backlash didn’t concern him, because “I’m worried about people feeling safe and comfortable on campus.”

Yet Zillennials aren’t any nicer to their own purported allies when they run afoul of the many ever-shifting rules of intersectionality. One of the most baffling anecdotes in the book involves the profanity-laced shutdown of the lesbian director of the transgender-positive biopic “Boys Don’t Cry” when she spoke at Reed College

Kimberly Peirce not only cast a cisgender actress (Hilary Swank) as a trans man, but “profited from the exploitation” of the person behind Swank’s character, Brandon Teena. And by depicting violence against Teena – which really happened – Peirce promoted violence against trans people. This is the new logic of the transgender movement, as Soave documents.

When a false rape accusation isn’t counted as ‘false’

The most important part of the book for the real-life rights of students is undoubtedly the chapter on #MeToo-era feminism.

Soave remains one of the few young writers willing to challenge both the moral and factual claims of fourth-wave feminism, which shares little in common with its predecessors except its blind faith in “recovered memories.”

He systematically reveals the ambiguity behind “rape culture” articles of faith such as “1 in 5” and “2-8 percent,” the latter an estimate of false reports of sexual assault. Readers who remember nothing else from the book should remember this: even the false accusations at the heart of Rolling Stone‘s discredited feature on rape at the University of Virginia would not be counted as false under prevailing definitions.

Soave gets to show off some of his own more serious research here: He helped debunk the “serial predator” theory of campus sexual assault by the since-discredited researcher David Lisak, whose work underlies the vast majority of campus sexual assault prevention policies.

His willingness to challenge this most sacred cow in campus culture – “believe the survivor” – is sadly undermined by Soave’s desire throughout the book to appear as an ally (another intersectionally loaded word) to activists who want nothing to do with him.

He refers to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which defames both conservatives and contrarian liberals as bigots, as a “widely respected organization” even as he questions its central claims. He uses the term “survivor” to refer to accusers whose claims – even something as minor as an impromptu hug – may not have been adjudicated.

Soave also “wholeheartedly” agrees that the process of gender transitioning – altering your body with hormones and possibly surgery to more closely resemble the opposite sex – is “a good choice for a whole lot of people.”

He’s trying to stake out a middle ground here with other trans-positive figures such as bioethicist Alice Dreger and writer Jesse Singal, whose contrarian work on trans issues has made them targets of trans activist mobs. But it would have been nice for Soave to apply the same scrutiny to core transgender claims, such as the attribution of mental-health problems to society’s failure to affirm trans identities, as he did with campus rape activists’ articles of faith.

These are relatively minor failings, however, compared with Soave’s overall accomplishment: writing a readable and reflective account of the pitfalls of woke activism for younger adolescents who are still persuadable.

Much like the Saturday morning teen sitcom “Saved by the Bell” was actually targeted toward kids entering junior high, Soave’s book could have its biggest influence with those who have yet to walk out of class in a political protest.

IMAGE: All Points Books

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.