New book outlines progressive challenges to education and responds with care

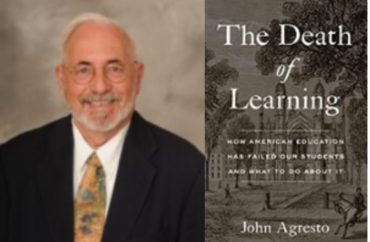

John Agresto, a longtime professor and retired president of St. John’s College in Santa Fe, recently wrote a book called “The Death of Learning: How American Education Has Failed Our Students and What to Do About It.”

Agresto’s book is singular because it takes criticism of the liberal arts seriously and proposes thoughtful and actionable responses.

It’s also easily readable but thought-provoking, brief but deep.

Agresto addressed opponents of the traditional liberal learning generously, finding a grain of truth in all of them. But he carefully distinguishes between good and bad responses. Critics have attacked and vandalized the liberal arts. However, Agresto shows us that it is possible to reform them in enriching ways.

He began by defining the liberal arts “not clearly vocational or pre-professional,” they are academic subjects such as history, literature, calculus, biology and philosophy. They are “the seeking of knowledge about important matters through reason and reflection.”

Agresto outlines and answers major criticism

First, he took up the objection that the liberal arts are not practical and won’t help people get jobs.

Agresto affirmed that vocational or professional training is valuable and essential for most people. He urged “humility” for highbrow critics who suggest that people without a fancy education are somehow dumber, less happy, or less moral than liberal arts majors.

Liberal arts majors should not lecture others “on ethics or social justice or how to be more ‘humane.’”

However, Agresto argued that the “habits of mind and character” cultivated by a liberal arts education could make students better at nursing, business and other practical professions. Liberal arts can teach persistence, attention to detail, and cause and effect relationships as powerfully as professional education.

He offered a vision in which practical trade or professional education and the liberal arts could learn from each other, as in, for example, professors of business and law lecturing humanities majors on their professions. His proposals recall ventures like the new College of St. Joseph in Ohio, which will affordably combine Christian liberal arts study with vocational education.

Agresto also argues for a positive multiculturalism against “diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

“The highest argument for a liberal education [is] that it g[ave] us an awareness of what is ours and serious insight into what is not ours,” Agresto wrote. A respectful study of our own institutions could be enriched by a deep study of the history, religion, and art of the rest of the world.

However, “for all its attachment to ‘criticism,’ the multicultural movement is amazingly uncritical,” he wrote. “That the west is racist, sexist, and the source of continued oppression is presumed,” he wrote.

A good multiculturalism shouldn’t mean indoctrination in bland diversity, narrow identity politics and hatred of our institutions.

Against the charge that the liberal arts need to be politicized, Agresto wrote that good education can make politics better, not the reverse.

“One reason it’s difficult to get politics out of the classroom is that it’s hard to get politics out of people,” he admitted.

Political commitment and animation in professors who have “the passion of St. Paul” makes the humanities “more exciting,” he wrote.

But canceling figures with whom we disagree distorts and limits our thinking and self-knowledge, Agresto rightly stated: “Because so many serious thinkers and books are now seen as ‘other,’ they are perhaps even more essential than ever for us to know.”

Additionally, liberal arts can help us understand politics in a deep sense that cuts beyond the lying, corruption, bland messaging and manipulation on all sides.

In response to those who criticize a liberal education for including views that upset people, Agresto rightly acknowledges that a commitment to open inquiry does not require educators to defend all speech. Slurs, insults, slander and the shouting down of opponents have no place in colleges and universities.

However, the free exchange of ideas, and right to respectfully argue a controversial position, is central to academic life. Abandoning those values would turn our universities into woke religious seminaries or “re-education camps.”

Though respectful, Agresto’s book doesn’t give too much credit to woke critics

Agresto’s book is remarkably fair. However, he doesn’t pull any punches.

“Let me sum this up as strongly as I can,” he wrote. “The last thirty years have seen the vandalizing of ever so much of higher education. The supposed reformers have entered the storehouse of centuries of accumulated knowledge, torn down its walls, thrown out its books, and topped its monuments. For all their brave talk of justice, they have carried out what has to be seen as the one of the most intellectually criminal act of the ages, the modern equivalent of burning the libraries of antiquity.”

“Liberal education is dying,” Agresto wrote, “not by murder but by suicide.”

Liberal arts can save us from the problems of academia, Agresto suggested

Agresto ended on a confident note: he believes that a good liberal arts education itself could inoculate us against academic nonsense and help us defend solid education.

He celebrated the liberal arts as an invitation to enjoy the reflections of some of the greatest minds that have ever lived and make their insights our own. This education offers “wonderful treasures” of great music, art, “fabulous literature, great poetry – and all of this for everyone, not just the elites.”

Human beings have minds that wonder about reality and hearts that long to know beauty and the truth, Agresto wrote. Liberal arts can speak to that wonder and that longing.

Though Agresto’s book has many virtues, its main weakness is its repetitiveness

In several different chapters, Agresto repeated criticisms of multiculturalism and social justice education to the point of redundancy, and he spent perhaps too much time outlining the arguments of critics who want relevance.

His argument also might have been stronger had he begun with a clear, simple definition of the liberal arts rather than several different definitions. That approach is nuanced, but it may lack clarity, especially for a wide audience.

Nonetheless, Agresto’s book is a thorough and powerful summary of the devastation of the education over the last several decades. It’s also a call for renewal, both by incorporating valid criticism and inviting us to rediscover the liberal arts in all their “stupendous magic.”

MORE: Online group provides classical, tuition-free liberal arts education

IMAGE: Jack Miller Center, EncounterBooks

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.