A ‘flexible’ hunger strike

A hunger strike helped topple the University of Missouri System’s president in November 2015, after two months of students protests regarding race relations and healthcare for graduate students.

University of Kentucky student activists took inspiration from this coup for their own causes, launching a “flexible” hunger strike that evolved into a 100 student-strong sit-in.

In order to avoid becoming a national embarrassment like Mizzou, UK administrators caved to activist demands across a wide range of progressive issues in less than a week.

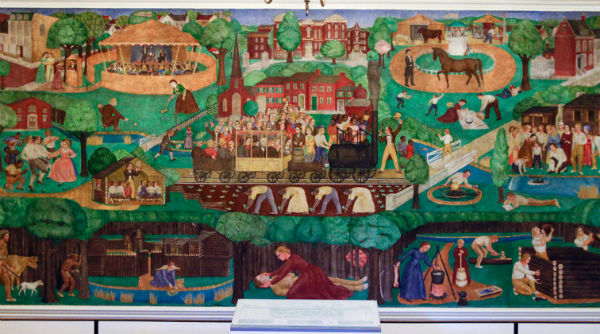

Though it started as a protest against the cost of food and housing for UK students, the Basic Needs Campaign later added unrelated racial issues, including the immediate covering and eventual removal of a mural (below) that offended some students.

Smelling blood in the water, activists pledged to occupy a building after the university had already agreed to “free meal swipes” for students who say they can’t afford food.

By the end, President Eli Capilouto had agreed without conditions to seven of the eight demands laid out by the protesters, and made concessions on the eighth, the campaign announced April 2.

The president was initially resistant to the purported hunger strikers’ demands, even refusing to meet with them until they started eating again. An administration spokesperson told The College Fix on the only weekend of the strike that Capilouto would not meet any further demands.

Yet Capilouto gave in two days later, after the Black Student Advisory Council joined the Basic Needs Campaign.

It was quite an accomplishment for a movement of roughly 300 students in which only six claimed to be not eating at all.

The rest agreed to single or multiday fasts, eating or giving up one meal a day, skipping one meal on a single day, or “create your own plan.” The campaign has not provided a breakdown of how many students agreed to each option.

MORE: Yale activists eat whenever they’re hungry, media call it hunger strike

13,000 students ‘cannot pay for the food they need to live a healthy life’

The campaign started early this year as an unofficial offshoot of UK’s official anti-hunger initiative, known as SSTOP Hunger: Sustainable Solutions to Overcome Poverty.

Housed under the university’s Department of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, SSTOP Hunger started after Capilouto signed a commitment in 2014 to end hunger. According to the campaign, the initiative officially launched the following fall.

The Basic Needs Campaign launched its hunger strike on March 27 to protest the university’s allegedly slow progress on ending food and housing insecurity on campus. Organizers claimed that “nothing has worked” to get Capilouto’s ear, because the university “puts profit over people.”

Their open letter to Capilouto conflated the student-led campaign with the university-led SSTOP Hunger initiative, telling students to find campaign updates on the SSTOP Facebook page and email an SSTOP address with questions.

The campaign cited a university survey from fall 2017 in which 43 percent of “surveyed students” self-reported that they “experienced some level of food insecurity in the past 12-months.” UK defines food insecurity as “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods due to lack of financial resources.”

Eight percent self-reported housing insecurity, defined as “inability to pay rent or utilities or the need to move frequently.” The university said 1,632 students completed the survey. (UK’s fall 2018 enrollment was more than 30,000.)

The campaign said it would continue striking until its three demands were satisfied: establishing and funding a physical Basic Needs Center, establishing a Basic Needs Fund, and creating a full-time Basic Needs staff position.

Activists blamed the UK administration for “decisions that make student food and housing too expensive,” claiming that “the US federal government’s standards say so.”

At the hunger strike’s peak, about 300 students were taking part. (The Chronicle of Higher Education put the figure at “some 300,” while a striker on day four said “about 300.”) Upon the campaign’s launch with 21 participants, six students said they wouldn’t eat until the three demands were met, while five would strike “between 2 and 7 days,” seven would eat one meal a day, two would skip a meal daily, and one would “skip meals every now and then.”

MORE: Rich Mizzou hunger striker who mocked women and poor wins ‘courage’ award

Capilouto issued a public response March 28, saying he would “never disrespect the concerns that have been raised or those who have raised them.”

He said the administration had reached out to the strikers to “show concern for their wellness” and to “assist them in any way” possible. Capilouto also linked to existing services and initiatives to meet students’ basic needs.

The campaign issued an annotated version of the president’s statement, in the name of the university’s SSTOP Hunger initiative. It claimed that 13,000 students “cannot pay for the food they need to live a healthy life” – without defining the amount or kind of food needed “to live a healthy life” – because existing programs such as UK LEADS only cover a fraction of them.

Asked to comment on the strikers’ response to Capilouto, and whether that would affect the university’s stance, spokesperson Jay Blanton told The Fix March 30 that Capilouto’s statement “speaks to where the institution is with respect to this issue.”

It’s censorship to tell students they can’t misrepresent university?

The Basic Needs Campaign’s indiscriminate use of SSTOP Hunger resources – implying the administration supported a campaign against itself – got its leaders kicked off the committee that oversees the university initiative.

The SSTOP Hunger staff adviser texted them that they could no longer be associated with the committee because “a hunger strike has crossed the line from community organizing to protesting.”

Having used the SSTOP Hunger Facebook page rather than create their own campaign Facebook page, student protesters also lost access to the page for much of March 30.

All its posts were “unscheduled” and it was “unable to update the public on our campaign,” the campaign told The Fix in an email. It was also banned from using the SSTOP Hunger all-student listserv and Google Drive for its own campaign.

It said that “only two students” had posted on the SSTOP Hunger page:

After many phone calls, text messages, and emails (9 hours), we were able to regain control of the Facebook page under the condition that we unaffiliate ourselves with SSTOP Hunger (name, logo, email, etc.). Since Facebook has certain rules about how long you have to be an admin for before changing Facebook page names, we were unable to change the page name, but we did change the logo, description, email contact, website url, etc.

After the nine-hour hiatus, the campaign declared it was being censored by the administration. Blanton, the UK spokesperson, told The Fix that “in fact, it was the administration that insisted that the [SSTOP Hunger Facebook] page be turned completely over to students.”

When the SSTOP Hunger page was created “from work or an initiative in an academic department,” some non-students “apparently” had administrative privileges, he said.

MORE: Prof stops eating to protest tenure denial, ends strike with tacos

Black students wanted to ban other students from scholarship

Capilouto’s April 1 refusal to meet with protesters until they ate turned out to be an unintentional April Fools’ Day joke.

On the same day, the fifth day of the hunger strike, the protesters said they would ignore the president’s “ultimatum.” The Basic Needs Campaign held a “People’s Assembly” at White Hall and announced they would “occupy” the hall until Capilouto met with them, even though the administration had already promised to provide free meals for food-insecure students. The campaign explained: “Administrators don’t acknowledge the full need. Show them we need more.”

The campaign also revealed that the Black Student Advisory Council had joined the cause.

BSAC’s demands, linked to every subsequent campaign social media post, included limiting the diversity-focused William C. Parker Scholarship to black students and removal of a Memorial Hall mural that they consider racially insensitive. The group also demanded that it be given a permanent seat on search committees for administrative officials.

The next day, Capilouto agreed to nearly every demand over the course of a live-streamed two-hour meeting.

In an email to the community after the meeting, Capilouto claimed that his “mind was further opened to [the protesters’] challenges and, frankly, to some of the shortcomings we have as an institution that aspires to be a community of belonging for everyone.”

The university has agreed to a permanent seat for BSAC members on search committees for administrative officials; standardizing the role of Diversity and Inclusion Officers; releasing the findings from a 2016 campus climate survey; staffing for a full-time basic needs center; and the establishment of a basic needs fund.

Capilouto didn’t commit to banning non-black students from the Parker scholarship, though. Rather, the university will “meet with” BSAC to “review the available data relative to the Parker scholarship, with the goal of strengthening and continuing to grow the program for black students, without diminishing our commitment to diverse students across the campus.” It will also review a similar scholarship for graduate students.

Reversing his decision from less than three years ago, Capilouto also agreed to cover the New Deal-era Memorial Hall mural that depicts the slavery of Kentucky’s past. It is “one of the only true frescoes in the United States,” according to the O’Hanlon Center for the Arts.

The president said he was disappointed in the “amount of progress” the school had made and that “we need to make better progress at a faster pace.”

The Basic Needs Campaign declared “We won” on Facebook that night. They ended their strike and said they “will be sleeping in their own beds tonight.”

The Black Student Advisory Council was more guarded. It said “our work is not done” and promised to “see these acts through.”

MORE: UChicago students vote to ignore food-justice activists

IMAGE: andrelteixeira/Shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.