Two top scholars leading a $30 million federally funded effort to “braid” indigenous knowledge into science are ignoring requests for comment to explain exactly what that looks like in practice.

The University of Massachusetts, Amherst last year was awarded a five year, $30 million grant — the largest grant in the school’s history — from the National Science Foundation to establish a new international science and technology center at which researchers would work to address issues related to climate change, biodiversity, and changing food systems.

The Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Science will take a “transdisciplinary approach” and use “community-based research” to facilitate “place-based studies and projects” while working with 57 indigenous communities at eight international hubs across much of the English-speaking world, according to a 2023 article from the university.

Sonya Atalay, the provost professor of anthropology at UMass Amherst and director of the center, and Jon Woodruff, one of Atalay’s co-principal investigators and a professor of geographic and climate sciences at UMass Amherst, have not responded in recent weeks to The College Fix’s requests for comments.

The Fix sought details on what the integration of indigenous knowledge with Western science looks like in practice and whether they could provide specific examples of how this integration has helped or can help address climate change or other related problems.

However, there are growing concerns among some scholars over the validity and efficacy of weaving so-called indigenous knowledge into modern science.

Jerry Coyne, professor emeritus of evolutionary biology at the University of Chicago, has been a vocal critic of the integration, and in a recent interview with The College Fix described “the attempt to put indigenous knowledge on par with modern science” as “distressing.”

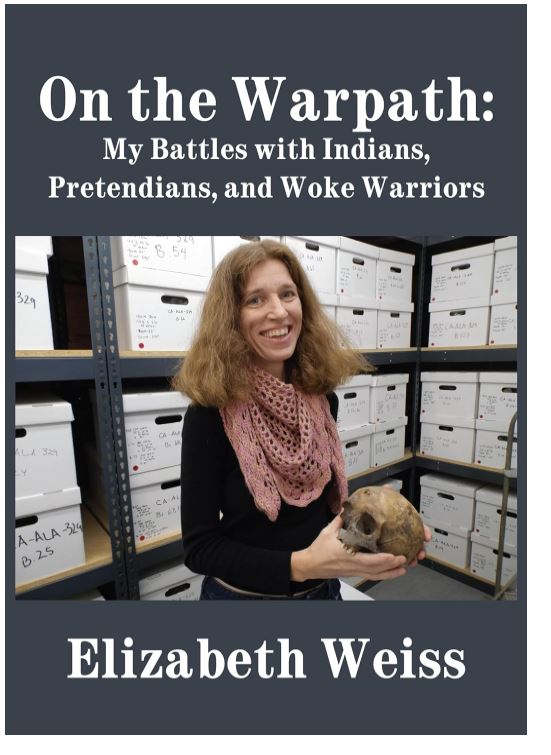

Elizabeth Weiss, a retired emeritus professor of anthropology and author of the new book “On the Warpath: My Battles with Indians, Pretendians, and Woke Warriors,” agrees with Coyne.

Elizabeth Weiss, a retired emeritus professor of anthropology and author of the new book “On the Warpath: My Battles with Indians, Pretendians, and Woke Warriors,” agrees with Coyne.

“The integration of ‘indigenous knowledge’ looks like scientists kowtowing to animistic beliefs and engaging in absurd rituals in order to continue to have access to skeletal and artifact collections,” she said in a recent interview with The College Fix.

When asked about the degree to which scientists in anthropology and related fields actually are embracing the kind of “braiding” proposed by Atalay and the new center at UMass, Weiss said: “Unfortunately, many scientists in general and anthropologists, specifically, are supporting this nonsensical idea that ‘indigenous knowledge’ can help us answer scientific questions.”

“This includes engaging in discriminatory practices, like preventing females from handling warrior remains or telling menstruating and pregnant females that some materials are too dangerous for them to handle in their weakened condition,” Weiss said via email. “It also means engaging in sage burning, hanging devil’s claw in shelving areas, and covering up ‘spiritually dangerous’ artifacts, for fear that ‘dark forces’ will be summoned.”

Additionally, Weiss said braiding looks like “fitting data to the mythology, rather than using data to come to objective conclusions.”

The Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Science is expected to host more than 50 scientists, including “more than 30 of the world’s leading Indigenous natural, environmental and social scientists” representing several indigenous peoples, the UMass website states.

The Center for Braiding Indigenous Knowledges and Science is expected to host more than 50 scientists, including “more than 30 of the world’s leading Indigenous natural, environmental and social scientists” representing several indigenous peoples, the UMass website states.

Its reported focus is “connecting Indigenous knowledges with mainstream ‘Western’ sciences to address some of the most pressing issues of our time in new ways.”

Its director, Atalay, was quoted in the article as saying the center’s vision “is that braided Indigenous and Western methodologies become mainstream in scientific research – that they are ethically utilized by scientists working in equitable partnership with Indigenous and other communities to address complex scientific problems and provide place-based, community-centered solutions that address the existential threat of climate change and its urgent impacts on cultural places and food systems.”

According to Atalay, the “braiding” of these two methodologies entails the process of “two-eyed seeing,” which was described in an earlier UMass Amherst article regarding Atalay’s work as a means to develop a better, “more rigorous and complete” understanding of the natural world through the integration of different knowledge systems.

Atalay also is reported to have stated that indigenous knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge have been increasingly acknowledged as valuable by the scientific community.

“Indigenous knowledge isn’t about going back to the past,” Atalay said. “It’s about recognizing that Indigenous knowledge systems carry tremendous information and value, and it’s shortsighted to think that current research practices founded on Western knowledge systems are the only or ‘right’ approach. If there’s something we can learn from Indigenous peoples that can help us all with this existential threat of climate change, I think that’s essential to further explore, understand, and incorporate.”

Articles from UMass Amherst also indicate Atalay and the center aim to “Indigenize university science curriculum” and develop programming for K-12 students.

When asked about alleged benefits and potential drawbacks to attempts to “braid” indigenous knowledge with science, Weiss wrote, “I cannot think of a single benefit.”

However, she stated, “The drawbacks are multiple, including wasting time and money on this nonsense, often at taxpayers’ expense. And, turning a once respected discipline into a farce.”

MORE: Efforts growing to ‘braid Indigenous knowledge’ into science, UChicago biologist warns

IMAGES: From top — National Science Foundation; Elizabeth Weiss; UMass Amherst

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.