The new sexual-consent app Good2Go may be a victim of its own timing.

It’s being marketed as a way for college students to “facilitate communication” with each other before sex and judge whether they are sober enough to consent. The app, which requires users to register with their mobile phone numbers, even went through beta testing with drunk college students.

But some publications, including The College Fix, have reviewed the app based on its ability to help resolve sexual-assault allegations or, conversely, lead to more confusion for campus tribunals and courts. Reports of colleges flubbing their federally required investigations of assault, by shortchanging accusers or railroading accused students, have filled the news this year.

That perception of the app’s purpose – as a legal instrument in an adjudication process fraught with perils – appears to have caught Good2Go by surprise.

In fact, in a phone call with The College Fix, Good2Go President Lee Ann Allman didn’t have a ready-made answer for a question faced by every app developer that collects personal information: under what circumstances Good2Go will turn over that data to authorities.

In fact, in a phone call with The College Fix, Good2Go President Lee Ann Allman didn’t have a ready-made answer for a question faced by every app developer that collects personal information: under what circumstances Good2Go will turn over that data to authorities.

Allman said the app was purely educational and not intended to be definitive in a sexual-assault investigation.

That sentiment was echoed by a civil-liberties group that told The College Fix the app’s usefulness in judicial settings was “limited at best” – and concerns about its privacy “should not be understated.”

“Affirmative Consent” and a Sexual-Activity Log

Good2Go was released days before California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law mandating that colleges use “affirmative consent” to judge whether student sex was consensual, also known as “yes means yes.” That law requires students to give “ongoing” consent, and not be “incapacitated” through alcohol or drugs, for sex to be considered legally consensual.

Good2Go was released days before California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law mandating that colleges use “affirmative consent” to judge whether student sex was consensual, also known as “yes means yes.” That law requires students to give “ongoing” consent, and not be “incapacitated” through alcohol or drugs, for sex to be considered legally consensual.

Many colleges individually have been moving to affirmative consent as well. In another sign that the federal government expects colleges to follow a certain path in sexual-assault investigations, the Department of Education recently told Princeton University that it must junk its “clear and convincing” standard for guilt and use the lower “preponderance of evidence” standard, common in civil trials.

Some reviewers have interpreted Good2Go through this context: sexual partners disagreeing about consent after booze-fueled liaisons, leading to school investigations, as well as general privacy worries.

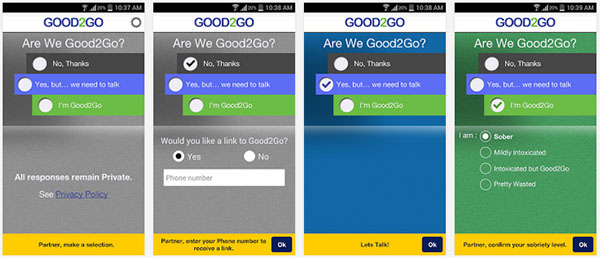

The Washington Post focused on Good2Go’s collection and retention of a person’s sexual history tied to their name and phone number and its “incredibly lax” privacy policy. The review also noted the app interface’s “odd” consent distinction between “intoxicated” and “wasted,” and how its sexual-activity log could be “inaccurate or misleading” in a trial.

The College Fix argued that campus administrators could construe an “intoxicated” person having sex – as registered by Good2Go – as unable to legally consent, and judge the initiating student guilty of sexual assault. It also faulted the app for using a one-time consent mechanism when California’s new law requires ongoing consent.

Education, Not Adjudication

But Good2Go wasn’t designed with any law or adjudication process in mind, Allman told The College Fix.

Though Good2Go strongly supports the new California law and its parent Sandton Technologies is based in San Diego, the timing of Gov. Brown’s bill signing was “a bit coincidental” with the app’s release, Allman said.

Rather than provide an evidence trail that is “admissible in any kind of official capacity” in a judicial proceeding, Good2Go is “simply a record, a data point” of two people before having sex, Good2Go spokeswoman Kate Rice said on the same phone call.

Attempts to devise a simple, unambiguous way to mutually agree to sex on campus go back to 1993, when Antioch College decided there was none. It started requiring students to give explicit consent at “each stage of intimacy.”

Reason’s Robby Soave mused in a column this June, as California’s “yes means yes” bill was being debated, why someone couldn’t devise a mobile app that would handle consent for college students and preempt later disputes about assault. Soave sees Good2Go as such an app, and so did the organizers of a rally for the California law last month, who called Good2Go “an app that leaves no blurry lines in what is sexual consent or not.”

Blurry lines or not, Allman said she and her husband were not thinking about evidence and litigation when they created Good2Go.

They had been following news about campus sexual assault and the proposed Campus Accountability and Safety Act throughout the spring and talking to their college-age children about the issue, Allman said.

The Allman kids “really didn’t know what they were supposed to be saying or asking or answering” with potential sexual partners, or how “being a young person on campus” might be affected by state or federal legislation, Lee Ann Allman said.

Though using an app “does not seem like the most direct route to getting consent” for today’s adults, college students don’t necessarily understand how consent works, Allman said. “These are very tricky waters” for young people to navigate around sex, and Good2Go is “a good first step.”

Get Drunk and Play With the App

True to app development, the Allmans sent out a pre-release version of Good2Go to college students across several states and campuses to see how it performed in the wild – “probably under 50 users,” Lee Ann Allman said. She declined to disclose the ratio of genders and sexual orientations in the test group.

Using the app “can’t be so cumbersome” that students who want to jump in the sack “have to wait five minutes” to formally register consent, Allman said. They were trying to hit the “sweet spot” in terms of requested personal information, and beta testers said that “once or twice” they used the app, “they get it,” she said.

(Slate’s Amanda Hess, in another mixed review, said it took her and her partner four minutes to get through all screens. In its own test, The College Fix and its “partner” for the experiment – a mobile industry veteran – got tripped up on screens directed alternately to “Partner” and “Owner,” referring to the phone’s owner.)

Just Like OKCupid and Mismatches

While Good2Go’s FAQ page says it will only release user data when the company determines “a proper request has been made by appropriate authorities, such as law enforcement or a university as part of an investigation,” Allman couldn’t elaborate on specific conditions in the phone call.

Spokeswoman Rice later sent a formal response: “If Good2Go receives a subpoena from a court of law, it will comply with the subpoena.”

Good2Go will only release records to college officials “as part of an official, formal campus investigation, and then only if it receives what it deems to be a valid request, in writing, from a legal representative of the college or university,” the formal response says. “Each request will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.”

Allman and Rice emphasized on the call that Good2Go wasn’t designed to satisfy any legal standard, explaining why its one-time consent mechanism and reliance on the consenting partner to judge her own sobriety doesn’t line up with the new California law.

“We understand that the initiator has to assess sobriety” regardless of who the app asks, Allman said. “You can always change your mind” and withdraw consent during sex, regardless of giving consent through Good2Go before sex. “It’s really no different if they used our app than if they gave a verbal consent” before sex and then things changed during intercourse, she said.

Rice compared Good2Go to the dating website OKCupid as to what consequences could flow from using the service: “Would OKCupid be responsible for a mismatch on their site?” Neither does Good2Go have responsibility if someone later claims assault after registering their consent through the app, Rice said.

Despite the beta test, the Allmans didn’t do wide outreach to campus administrators before launching the app. Lee Ann Allman said they had “some” discussions with administrators, and her son is talking to his own college officials, who are “very intrigued” by the app and “want to be sure it works well” with campus policies.

“It’s going to take some time for all those contacts to be made,” and the Allmans have had “some initial conversations” with groups that advocate for due process, Lee Ann Allman said.

What Is ‘Intoxicated But Good2Go’?

One question that Good2Go won’t answer is exactly what its inebriation categories mean, which has confused some reviewers.

One question that Good2Go won’t answer is exactly what its inebriation categories mean, which has confused some reviewers.

Consenting partners can register themselves as “sober,” “mildly intoxicated,” “intoxicated but Good2Go” and “totally wasted.” Only the last category stops the consent process in its tracks. The categories are “meant to be vague,” Rice said.

Regarding privacy and hacking worries, Good2Go uses Amazon Web Services for hosting, which has “state of the art” security, Allman said. There’s no monetary value in the sexual-activity data that Good2Go stores since it’s not trying to monetize the data, she added.

(The Post noted in its review that Good2Go doesn’t “currently” share records with marketers because, according to Allman, its “initial focus is to drive adoption.”)

Its own staff won’t be deceived by phishing or social-engineering attacks in which hackers trick those with database credentials to turn over their passwords, Allman said.

Be Wary of ‘Enterprising Prosecutors’

After testing Good2Go, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education was less concerned that students could be found guilty of rape solely because their partners described themselves as “intoxicated” before sex. The civil-liberties group is more worried about how prosecutors could use a student’s entire sexual history from Good2Go.

“The privacy concerns created by the Good2Go app should not be understated,” Senior Vice President Robert Shibley told The College Fix by email. “Students should be wary of entering data about the intimate details of their sexual lives at any time, but especially when they lack express and clear guarantees that the data will kept in strict confidence.”

Shibley said that “enterprising prosecutors” could subpoena data that cover far more than a single liaison. The “entire history” of Good2Go data for a particular student could be used “to show a student’s pattern and practice, or modus operandi,” and obtaining this data could pose “fascinating 4th Amendment questions.”

Good2Go can’t help accused students reach the burden of proof they need under California’s new law, Shibley said. “Indeed, other than videotaping the entire situation, it is difficult to conceive of any way, technologically or otherwise, for a person to prove that they had affirmative consent at every stage of a sexual encounter.” (Videotaping as a defense is actually on the rise, according to one professor.)

Student data from the app can “only establish the mindset of the participants at the moment” they registered consent in Good2Go, meaning it won’t be useful “in cases where someone claims to have revoked their consent” or where an accuser claims to have been “coerced” into app consent, Shibley said.

The very complication of using the app – Shibley called it “not all that simple” – means that a “truly incapacitated person would almost certainly be unable to use the application at all.” That serves as evidence that a person “was not too incapacitated to offer consent, at least at the time the app was used,” Shibley said.

Greg Piper is an assistant editor at The College Fix. (@GregPiper)

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

IMAGES: Lee Ann Allman/Twitter, Good2Go

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.