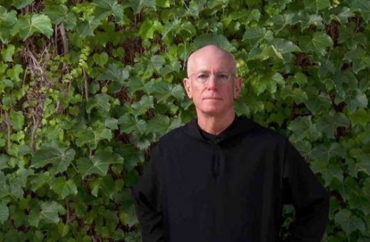

Father Columba Stewart delivers prestigious NEH lecture

The work of a Benedictine monk to preserve historical manuscripts has taken him from the grounds of St. John’s University in Minnesota, to the Middle East, to sub-saharan Africa and beyond.

On Monday, the Rev. Columba Stewart’s travels took to him to the Warner Theater in Washington D.C., where he delivered the Jefferson Lecture, billed as the National Endowment for the Humanities’ most widely attended annual event and the highest honor the federal government bestows for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities.

Stewart, wearing his full traditional religious habit, detailed during the prestigious lecture the effort to save from destruction historical manuscripts around the world by the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library, where he serves as executive director.

The monk and scholar issued a stark warning during his talk on the need for humanity to understand each other in a message that transcended race, religion and political differences. To his diverse audience, his message was a simple one that has been his first rule of life as a Benedictine monk: “Listen.”

“We are at great risk of losing the ability to listen,” Stewart said, “and therefore losing our ability to understand.”

“The terrain for rational discourse has shrunk to a narrow strip between camps defined and limited by their political views, religious beliefs, racial or ethnic identity,” he said.

Stewart said that “the discipline of listening is now an endangered art.” But, he added, “equally endangered are the stores of wisdom contained in the manuscripts of the world, targeted by those fearful of difference.”

The Hill Museum and Manuscript Library has dedicated itself to preserving historical manuscripts on microfilm, especially those in areas where they may be destroyed. Stewart’s work has led him across the globe, from the deserts of Iraq and Mali to the jungles and savannahs of Ethiopia. Manuscripts have been preserved in Lebanon, Syria, Austria, France, and everywhere in between.

And his organization’s work could not be more timely. With the invasion of ISIS into western Iraq in 2014, the Syrian civil war, and terrorist groups active in Africa, many manuscripts and priceless historical artifacts have been destroyed. But thanks to the work of the library, microfilm copies were made of many of them, preserving the manuscripts for future generations.

Stewart invoked the centuries old stereotype of a monk studiously hunched over a book at a desk, pen in hand, to describe the work to which he has devoted his life.

“A belief in the power of words” drove monks from centuries ago to painfully copy manuscripts — and the ones of today continue to preserve them, he said.

“To know what is most important to [a] people, to understand the questions they asked, and what gave them purpose and identity, we need to read their manuscripts,” Stewart said.

In his worldwide mission to preserve those manuscripts, the Benedictine monk has found himself in some of the most volatile places on Earth.

In Syria, Stewart said, a Greek orthodox patriarch and his Assyriac counterpart in Aleppo were prominent supporters of his work several years ago. But as the situation in Syria rapidly deteriorated with the civil war and the rise of the Islamic State, the two clergymen disappeared and were never heard from again, he said.

Many of the physical manuscripts that the two helped the library preserve were subsequently destroyed, but thanks to the microfilm project, they live on elsewhere.

The origin of the preservation project traces back to the aftermath of World War II and the ongoing Cold War’s threats of nuclear winter. By the turn of the century, Stewart said that 85,000 manuscripts had been preserved in microfilm. And not just Christian manuscripts, but Jewish, Islamic and other historical manuscripts too. He noted that all three of those intellectual traditions are driven by people who listen.

“It is often said that Jews, Christians and Muslims are people of the book, even if not of the same book. We are, all three traditions, people of many books,” Stewart said. “As are those who follow ancient philosophies and other ancient traditions.”

“In those books are stories, reflections on stories, ideas spun by human observation and experience. Attempts to trace how our universe exists and functions in space and time. These books changed the world because their words were heard. They were taken seriously. Serious enough to prompt rebuttal or controversy, admiration or adoption. But they were heard.”

MORE: Clueless students call white-robed priest a Klansman

IMAGE: courtesy image

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.