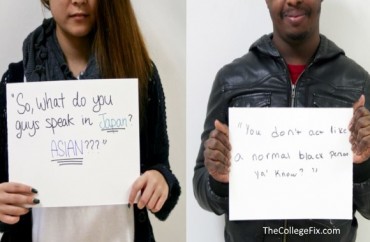

Emory University psychology Professor Scott Lilienfeld is challenging the seemingly universally accepted concept of the microaggression.

After reviewing many studies on the topic, Dr. Lilienfeld argues in his paper “Microaggressions: Strong Claims, Inadequate Evidence” that microaggressions lack scientific proof, and therefore should not be included in workplace or campus diversity training.

Moreover, he said he believes that the term microaggression is misleading, as it implies conscious intent to harm, and thus should be abandoned.

“The scientific status of the microaggression research program is far too preliminary to warrant its dissemination to real-world contexts,” he writes in his 2017 scholarly article published in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Lilienfeld told The College Fix in a phone interview that he became interested in studying the microaggression phenomenon after noticing its ubiquitous discussion on college campuses, faculty meetings, and the corporate world.

“I began reading the literature, and became more curious and more concerned when I realized that there was hardly any evidence supporting the concept of microaggressions,” Lilienfeld said.

When universities and corporations began providing microaggression detection and avoidance training, the underlying assumption was that the concept itself had been subjected to rigorous scientific scrutiny.

Lilienfeld counters that this is simply not the case.

“We know that microaggressions are correlated with negative mental health outcomes, but that finding may be confounded with a person’s pre-existing personality or mental health condition. Because microaggressions are determined by self-report, it is difficult to prove that they cause mental health problems,” Lilienfeld said.

MORE: Saying ‘America is a melting pot’ is a microaggression, Purdue class teaches

MORE: Penn State asks students to report microaggressions to administrators

The fundamental flaw, according to Lilienfeld, is the self-reported nature of the microaggression coupled with its broad definition.

“Because they are totally in the eye of the beholder — anything you say could be labeled as a microaggression,” Lilienfeld said. “In the current literature, if someone is offended by something, it is a microaggression. You simply cannot progress scientifically in this way or expect to resolve racial tensions on a college campus.”

“Because they are totally in the eye of the beholder — anything you say could be labeled as a microaggression,” Lilienfeld said. “In the current literature, if someone is offended by something, it is a microaggression. You simply cannot progress scientifically in this way or expect to resolve racial tensions on a college campus.”

Moreover, Lilienfeld argues that research on microaggressions does not draw upon key domains of psychological science, including: psychometrics, social cognition, cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavior genetics, and personality, health and industrial-organizational psychology.

Ultimately, he recommends entirely eliminating the term microaggression from use.

“Though the study of microaggressions has revealed important biases, the term is a terrible one because it implies that the intention of the person is aggressive in nature and aggression implies the intent to harm,” he noted in a phone interview.

Lilienfeld said he believes that racism does persist on college campuses and in the workplace, however he is concerned that an overuse of microaggression training may actually heighten racial tensions.

“Concern about microaggressions may make both sides more defensive,” Lilienfeld said. “Minority individuals may become hyper vigilant to recognize any signs of danger from speech or action. Conversely, majority members may begin to feel defensive because they have to watch every single thing they say.”

“Both sides need to talk to each other more not less. By handing out a list of phrases that you should not say because they are microaggressions stigmatizes speech and shuts down dialogue rather than encourages it,” Lilienfeld said.

MORE: Black Harvard prof — Giving minorities safe spaces does more harm than good

MORE: Being a ‘victim’ has become a badge of honor on campus

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

IMAGE: Shutterstock

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.