‘Contract grading’ billed as revolutionary education practice

A literature class at Davidson College this fall will use “contract grading,” allowing students to pick ahead of time their grade for the class and the workload they need to complete to earn it.

The offer is posed by Professor Melissa Gonzalez for her Introduction to Spanish Literatures and Cultures course, SPA 270, at the private liberal arts college in Davidson, North Carolina.

She is one of several professors across the nation who allow this pick-your-own grade method, billed as a way to eliminate the student-professor power differential and give students control of their education. But critics contend it is just another example of how colleges coddle students from the harsh realities of the real world, which includes competition and goal expectations.

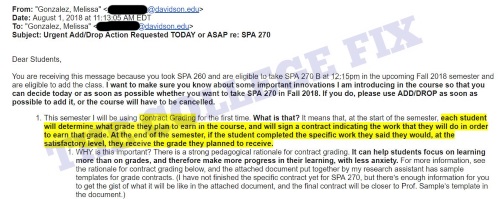

As for Gonzalez, she argues there is “a strong pedagogical rationale for contract grading” in an Aug. 1 email to students obtained by The College Fix. “It can help students focus on learning more than on grades, and therefore make more progress in their learning, with less anxiety.”

Gonzalez did not respond to repeated email requests for comment from The College Fix.

“I aim to foster classroom environments that are radically democratic and empower intellectual risk-taking,” Gonzalez states in her profile on the school’s website.

In her email, Gonzalez urged her former students to sign up for SPA 270, indicating that only two students have enrolled thus far and the class is in danger of being canceled.

“I want to make sure you know about some important innovations I am introducing in the course [contract grading] so that you can decide today or as soon as possible whether you want to take SPA 270 in Fall 2018. If you do, please use ADD/DROP as soon as possible to add it, or the course will have to be cancelled,” she wrote.

Gonzalez is a Hispanic Studies professor who also teaches in the Gender and Sexuality Studies department. In her email, she told students they could “sign a contract indicating the work that they will do in order to earn that grade.”

“At the end of the semester, if the student completed the specific work they said they would, at the satisfactory level, they receive the grade they planned to receive,” her email states.

To support her claim that contract grading improves the academic experience for students, Gonzalez cites a 2009 research paper by scholars Peter Elbow and Jane Danielewicz.

“The contract helps strip away the mystification of institutional and cultural power in the everyday grades we give in our writing courses,” according to the research paper.

“Using the contract method over time has allowed us to see to the root of our discomfort: conventional grading rests on two principles that are patently false: that professionals in our field have common standards for grading, and that the ‘quality’ of a multidimensional product can be fairly or accurately represented with a conventional one-dimensional grade. In the absence of genuinely common standards or a valid way to represent quality, every grade masks the play of hidden biases inherent in readers and a host of other a priori power differentials,” it adds.

In their paper, Elbow and Danielewicz also contend that contract grading is “used frequently, but discussed rarely. A Google search reveals a surprisingly large number of teachers who use some form of learning contract in various disciplines for diverse goals.”

Along with her email, Gonzalez attached two contract grading templates designed by other professors who also use the method: Cathy Davidson of CUNY and fellow Davidson College Professor Mark Sample.

Davidson, in a blog post on the grading method, refers to it as “an act of community.”

Contract grading has also been referred to as “specs grading” in a 2016 op-ed in Inside Higher Ed by Linda Nilson, director of the office of teaching effectiveness and innovation at Clemson University. She explains that “course grades are based on the bundles of assignments and tests that students complete at a pass/satisfactory level.”

“Bundles that require more work, more challenging work or both earn students higher grades. No more points to painstakingly allocate and haggle over with students. By choosing the bundle they want to complete, students select the final grade they want to earn, taking into account their motivation, time available, grade point needs and commitment,” Nilson stated.

“If a student chooses a C because that’s all he or she needs in your course, you can respect that. Under such conditions, students are often more motivated to learn because they have a sense of choice, volition, self-determination and responsibility for their grade, as well as less grade anxiety.”

But not all students are convinced it’s a good idea, including Davidson College senior Kenny Xu, who is majoring in mathematics.

“It degrades trust in your achievement by outside authorities, including employers, grad schools, scholarships etc.,” he told The College Fix. “Imagine if an employer saw that you got an A not because you were truly one of the best in the class but because you fulfilled some requirement YOU personally set. Would he really trust that A? I think not.”

“Colleges are increasingly viewing themselves as a support system rather than an institution of learning,” Xu added. “Learning is not supposed to be easy, or comfortable. Excellence requires that you step out of your comfort zone and compete. Colleges are becoming shelters, which is not what this country nor what this generation needs.”

MORE: White, male students called on last in some classrooms

IMAGE: Alex Millos / Shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.