Gay, yet socially conservative. Republican Trump supporter, yet beloved on a liberal campus. Former leftist turned Reagan devotee. Jefferson Adams’ career spans four decades and includes expertise in espionage and an unlikely circle of friends.

Consistently ranked one of the most liberal colleges in the nation, Sarah Lawrence College prides itself on the admittance of applicants that stand out from a crowd. From tortured writers to theater geeks, the school has a strong affinity for misfits.

It’s not far-fetched to encounter Birkenstock-sporting artists with colored hair and Marxist sensibilities walking the quad. Nude lesbian dance parties are also not out of the question.

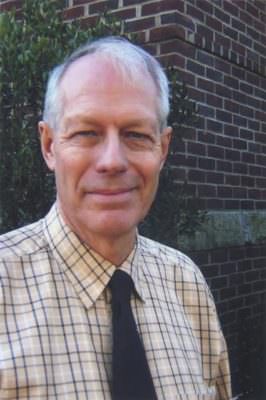

But wander to the gym on the southernmost part of campus and peer inside at the swimming pool and you’re likely to spot retired history professor Jefferson Adams doing his daily laps.

Adams is perhaps Sarah Lawrence’s most intriguing anomaly.

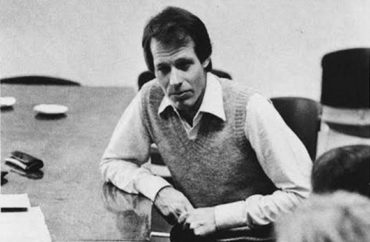

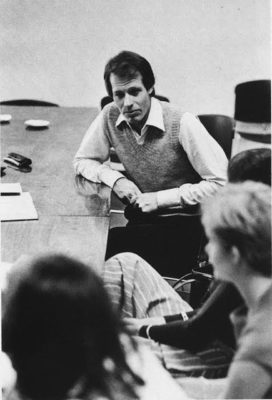

These days, he mostly ventures to campus for his regular exercise, but when I first met him he stood at the front of a lecture hall, smartly dressed in a sports coat and tie. Tall, trim and armed with a salient baritone, he launched into a steady but effervescent telling of the end of the Second World War.

Professor of European History for more than four decades, from 1971 to 2015, Adams gained the distinction of being Sarah Lawrence’s only outspokenly conservative faculty member.

Professor of European History for more than four decades, from 1971 to 2015, Adams gained the distinction of being Sarah Lawrence’s only outspokenly conservative faculty member.

During his tenure, he consistently strayed from campus orthodoxy, adopting a range of iconoclastic stances from support for the Iraq War to his endorsement of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential race.

He stood firm as a man with conservative convictions in a staunchly liberal institution. Despite his contrarian views, Adams thrived behind ideological enemy lines, forming intimate friendships with many people on the other side of the political spectrum.

For instance, he became the “Don” (the Sarah Lawrence equivalent of an advisor) and professor of Rahm Emanuel, the future Democratic mayor of Chicago, with whom he enjoyed an equally close and contentious rapport that would later be documented in The New Yorker.

“There’s a lot of Texan in me,” Adams told The College Fix in a recent interview. “You don’t let many things hold you back. You often defy the odds. … It’s very individualistic. … It’s never bothered me terribly to be marching to my own drummer.”

Reality of life

Adams’ biography reads like a catalogue of displacement and subsequent self-direction. His mother, a child of German parents, died of tuberculosis two years after giving birth to him. His father, an oil field worker for Texaco whom he regarded more like a grandfather, was twice his mother’s age and too old care for him.

Born in Houston, Adams lived the first few years of his life on a farm with his German grandmother before moving to Boulder, Colo., in fourth grade, where his aunt raised him.

Perhaps this imperfect upbringing birthed his desire to know the world not as it should be but as it is with all its picadillos and flaws. If Adams is committed to any philosophical outlook, it’s one not defined by abstract theory but grounded in the reality of life.

When Adams arrived at Stanford University to study European history as a college student in the early 1960s, he was rapidly disillusioned. Though he enjoyed his courses, he felt increasingly sheltered from the realities of the world, especially in contrast to his peers who were enjoying California’s temperate climate and palm trees.

Raised a fervent opponent of Richard Nixon and Barry Goldwater, he identified at that time as a Democrat, and had gladly volunteered in college to drive Democrat voters to the polls.

After Adams’ father died during his junior year, it prompted him to take a break from Palo Alto. He traveled to Germany where he took a job loading freight cars in a factory on the Rhine. After four months, one of his German co-workers invited him home for dinner with his family, a gesture that deeply touched Adams, who found an easy camaraderie with blue-collar workers. Here was the real-world experience that had eluded him in the classroom.

After returning to Stanford and completing his degree, he continued on to the doctoral program at Harvard. In his graduate years, he attended anti-Vietnam protests.

However, he remained suspicious of much of what he observed around him. After the student unrest of the late 1960s, he considered abandoning a career in higher education altogether. Yet it ultimately lacked the intellectual stimulation that the study of history offered, and he decided to take his chances in the academic world.

Breaking the mold

Thus he arrived at Sarah Lawrence College in 1971.

Adams was well-suited to Sarah Lawrence in more ways than one. At a young age, Adams realized he was gay, a trait that met no hostility on one of the country’s most historically LGBT-friendly campuses and that, on the surface, made him an even more unlikely candidate for conservatism. However, he had come to terms with his sexuality early on and never found it to be a major hurdle.

Adams was well-suited to Sarah Lawrence in more ways than one. At a young age, Adams realized he was gay, a trait that met no hostility on one of the country’s most historically LGBT-friendly campuses and that, on the surface, made him an even more unlikely candidate for conservatism. However, he had come to terms with his sexuality early on and never found it to be a major hurdle.

“Since it’s never really arisen in my professional life, either at the college or elsewhere, the main question is its relevance,” Adams told The Fix. “At the same time, I’ve never tried to keep it a secret, although gay life, in my opinion, was far more interesting when a semi-mysterious aura existed, and it did not try to imitate straight bourgeois marriages.”

Adams is adamant that his sexual orientation has little to do with his world view. Perhaps this is also why he does not see it as inconsistent with his politics.

“It will add an important element to your life,” he said. “That’s undeniable, but it doesn’t really define you as a person.”

‘Let them decide for themselves’

It was after several years teaching at Sarah Lawrence that he took a rightward turn.

“In my case, there was such a glaring discrepancy,” Adams said. “I was espousing all this liberal stuff but if you really pressed me on some issues, they were clearly at odds with my fundamental values. I had just accepted too many things unquestioningly. I was lazy.”

Adam’s voice has an uncharacteristic ring of self-criticism. Complacency is not Adams’ style, and he has always been a steadfast emissary of the individual conscience.

Asked for his thoughts on political neutrality in the classroom, he responds: “I never thought you could convert somebody. All you can do is expose them to a wider perspective of differing views and let them decide for themselves. … It has to come from the deeper wells of the person.”

Reagan Revolution

And come from the deeper wells it did for Adams, when, in 1976, having lost  the nomination for president, Ronald Reagan delivered an address at the Republican convention. That was the turning point.

the nomination for president, Ronald Reagan delivered an address at the Republican convention. That was the turning point.

“I was amazed. I said, ‘This guy has a future,’” he said. “People were saying he was too old. … Groupthink took over and they were all proved wrong. That ‘76 speech was truly extraordinary.”

Despite its popular progressive branding, Adams came to see Sarah Lawrence more as a libertarian institution, in many ways analogous to the spirit of America itself.

Home to a unique pedagogy defined by a high premium placed on biweekly, individual meetings between professors and students, it has only minimal course requirements. Additionally, while at another university, a professor would have to deal with various deans and department chairs to create a new course, the administration at Sarah Lawrence encourages such creativity and provides a great deal of leeway. In retrospect, Adams feels especially grateful to the college for having allowed his own entrepreneurship to emerge.

Year of the spy

This vision came to fruition when Adams identified an unexploited market niche: espionage. That’s right. Professor Adams developed a penchant for spies.

In the early 1980s, while working as a consultant for a book club, Adams received a manuscript on the Richard Sorge spy-ring in Tokyo to review and how little he knew about such an important episode, as the intelligence factor had been conspicuously absent in his own education.

In 1985, the so-called “Year of the Spy,” he introduced a new course to the college: Diplomacy and Intelligence in Modern History. Despite his open conservatism, Adams’s classes emerged as major hits amongst an overwhelmingly left-leaning student body. This particular course was the most over-registered that fall. Soon thereafter, he was awarded a year-long fellowship at the Hoover Institution which culminated in a prize-winning article titled, “Crisis and Resurgence: East German State Security.” Other publications followed, including a large historical dictionary of German intelligence and, most recently, a history of Cold War espionage.

It is noteworthy that Adams also launched an annual lecture series in international affairs, bringing to campus a variety of unconventional speakers who ranged from a former KGB general to the foreign secretary of Pakistan to the U.S. Army lieutenant colonel who tracked and captured Saddam Hussein. It was usually standing room only.

Make America Great Again

Adams began closely monitoring the 2016 election and immediately abstained from the Republican establishment’s fierce dislike of Trump. When Trump was elected in 2016, Adams was unsurprised. He had long caught on to the conservative backlash forming in the United States and resisted mainstream media predictions of Hillary Clinton’s inevitable victory.

“That’s what you learn in history. You can lay odds on certain things, but there’s nearly always an element of surprise,” Adams notes.

This is certainly true if one were to have laid odds on Professor Adams himself: Gay, yet socially conservative. Republican, yet beloved on a liberal campus. Endowed with an intellectual’s love of ideas, but captivated by the nitty-gritty reality of espionage.

“I’ve seen it happen over and over again in life. Just don’t accept conventional wisdom without a large measure of skepticism. So much of the time it simply doesn’t work out the way people anticipated,” Adams remarked, reflecting on his career.

If circumstance has forced Adams to observe institutions as an outsider, it has allowed him to observe their innards more clearly and to place his bets accordingly.

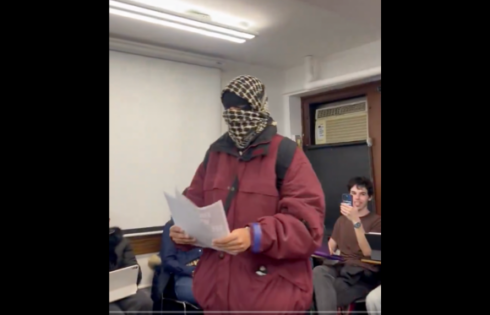

The Trump presidency has been controversial, unpredictable, and catalyzed overwhelming opposition at liberal safe havens like Sarah Lawrence. The consequent social pressure would impel the average person to fall in line. But one thing is certain: The professor is a supporter and he’s not budging.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.