‘Annnnnnd we got ANOTHER contact report so this test doesn’t even count,’ one mother complained

K-12 public school performance nosedived last school year, and people really noticed. As the Brookings Institution put it back in March, “Almost everyone is concerned about K-12 students’ academic progress.”

Brookings scholars found from surveys that “Almost three-fourths (71%) of US adults are concerned about K-12 students’ current academic progress.” They opined, “Very few economic, political, or social concerns share this level of agreement in the population.”

Those worries were well-founded. Take my own Washington state. The Washington Student Achievement Council found, unsurprisingly, that families say “children are spending less time on learning activities than before the pandemic” and have “less frequent live contact with teachers.”

The Student Achievement Council also found that “One out of four public high school students in Washington received a grade that does not earn them credit during the 2020-2021 academic year as of March 2021.”

And, yes, that is a significant decrease in performance, as there was “a 42 percent increase in the proportion of high school students in Washington receiving grades that do not earn them credit in the 2020-2021 academic year compared to the prior year.”

Staring down such dismal results, many K-12 school systems and colleges are doing what they can to fudge things. The state of Oregon simply said that students don’t have to know things to graduate from high school for the next several years. Many universities suspended standardized testing requirements for the foreseeable future.

But even with the standards lowered and the gates relatively wide open, kids are not flocking to college.

The Student Achievement Council found, “Fewer high school seniors in Washington have completed a FAFSA during the 2020-2021 academic year compared to the previous year,” and predicted, “The drop in financial aid applications may signal the potential for a lower postsecondary transition rate in the coming year.”

That was last school year, with distance learning being close to the norm. This year, schools are somewhat more open, but with important annoyances thrown in. Masks, of course. More frequent shut downs for weird reasons. Mandatory tests not just for kids who are suspected of having COVID but for those who have come in contact with them. Quarantines on top of quarantines.

Monica Marier is a friend of mine who has school age children. She wrote on Facebook, “Argh. Stuck in a car waiting hours for a PCR test for [her daughter]. (Contact alert, no symptoms)” and followed that up, hours later, with “Annnnnnd we got ANOTHER contact report so this test doesn’t even count. [Cuss word.]”

In a direct message, she added, “we were sent home and told to get a test due to a positive contact for our Kindergartener. It took 3 attempts, each taking several hours including wait time. Most testing areas around us require appointments which are scarce and the few available were an hour away. (1st time, they ran out of tests. 2nd time, the lab assistant wasn’t allowed to help us, and we couldn’t get the kid to comply. 3rd time after a 2 hour wait it took 3 adults to get a sample.) Then when we got home, we received a new call that told us there was a more recent contact, so this test did not count. We would need to get another one no sooner than 24 from now. Both of us having jobs, this was not possible. We’d already taken too much time off and by the time the results came in the quarantine would be over anyway. We’re opting to keep her home to the last required date rather than go through this again. Currently her entire class and teacher is home in quarantine. They too are having trouble getting access to PCR testing.”

Data visualization artist Matt Shapiro wrote on Twitter that because of scenarios like this one, “From a schooling perspective, many kids are actually better off getting COVID than *not* getting it,” because of contact tracing and a definition of “close contact” that is “a masterpiece of technocratic absurdity.”

By and large, in public schools, “your child is a close contact (and must quarantine) if she didn’t wear a mask and was within 3 feet of a positive individual for 15 minutes in an indoor setting [or] did wear a mask and was within 6 feet,” Shapiro wrote.

“But! If your child tested positive for COVID in the last 3 months… they don’t even check them. They are instantly *not* a close contact and do not have to quarantine. So the kids who *don’t* contract COVID have to [do] the hokey-pokey all year long with school attendance and quarantine but the ones who *do* just get to go to school and not worry about it. Getting COVID = stability,” he added.

I'm looking through a lot of school policies on COVID and quarantine and one insane thing I've noticed:

From a schooling perspective, many kids are actually better off getting COVID than *not* getting it.

Let me explain: /1

— PoIiMath (@politicalmath) September 7, 2021

Consequently, parents are existentially tired of this nonsense. Or, to use the current buzz words, burned out.

A survey released last week by the app Lingokids found that 59 percent of moms and dads in this country of kids aged 2-8 are experiencing “parental burnout,” which the news release defined as “a form of physical and emotional exhaustion…so intense that parents who were once operating at a high-functioning level found themselves struggling to show interest when their children want to show or talk to them about something.”

In fact, Lingokids found that “more than half of parents reported that they have less interest in directly managing their child’s learning this year (52%).” If you don’t think that will have demonstrably bad results in their children’s education, then this very tired parent would like to have what you’re having, and make it a double.

MORE: College financial aid sees huge drop in high school applications under COVID: report

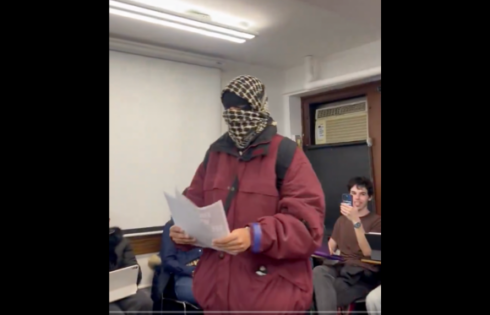

IMAGE: Olena_Yakobchuk.shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.