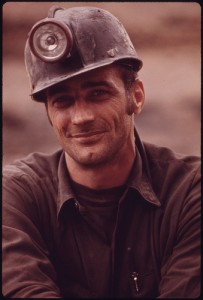

“Discontent is a mild word,” says Phil Smith, spokesman for the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). He is looking for the right word to describe the rising anger in the country’s coal mining communities: They are concerned, he says, that “their voices aren’t being heard, that after decades of providing a vital service to our country they are being kicked aside unnecessarily.”

That discontent may have significant consequences come November. The battle over the coal industry—for many years now a staunchly Democratic constituency—pits blue-dog Democrats against their “progressive” counterparts. It’s San Francisco against Tuscarawas County: one of the top coal-producing counties in Ohio.

But the clash has been long-coming. In fact, the president himself predicted it, on the campaign trail in 2008. At a stop in San Francisco, he described his energy policy to a reporter:

What I’ve said is that we would put a cap-and-trade system in place that is as aggressive, if not more aggressive, than anybody else’s out there. . . . So if somebody wants to build a coal-powered plant, they can; it’s just that it will bankrupt them because they’re going to be charged a huge sum for all that greenhouse gas that’s being emitted.

To his credit, he qualified his antagonism to coal, saying that “if technology allows us to use coal in a clean way, we should pursue it,” but four years later, this administration has shown a staggering antagonism to coal, preferring to embark on “what could be the most far-reaching environmental regulatory scheme in American history,” as Time’s Bryan Walsh wrote admiringly. And the goal of that regulatory scheme, spearheaded by EPA administrator Lisa Jackson, is not to create a “clean coal” industry, but to eliminate the country’s coal industry altogether.

The progressive Left has long condemned coal as environmentally unfriendly, but no administration has actively worked to cripple development of the resource responsible for nearly half of America’s electricity. The National Mining Association reports that coal is the most affordable source of power per million Btu (British thermal unit, a standard measure of energy), “historically averaging less than one-quarter the price of petroleum or natural gas.” It also comprises 30 percent of the country’s total energy production and 21 percent of its total energy consumption. United Mine Workers of America president Cecil Roberts has called the United States “the Saudi Arabia of coal.” The industry employs 136,000 people directly, and for every added coal mining job, 3.5 jobs are created elsewhere.

But the president and many congressional Democrats have worked to strangle the industry in the name of environmental health. In 2009 the White House backed the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill, which, had it passed the Senate, would have required an 83 percent carbon-dioxide emissions reduction by 2050. The Treasury Department calculated the cost to families of four at $1,800 a year; House Republican leader John Boehner predicted a cost of $3,100.

Two years later, circumventing Congress, the EPA published its Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS) rule, which would limit the emission of “mercury, non-mercury metallic toxics, acid gases, and organic air toxics.” Because the largest pollutants are power plants, the rule would force 40 percent of the nation’s coal-fired plants to retrofit with technology to reduce emissions to maximum achievable control technology (MACT) standards within three years.

The problem, says United Mine Workers spokesman Phil Smith, is that plants “simply cannot meet that three-year deadline. Even if they wanted to, they can’t.” The UMWA is backing a bill, co-sponsored by West Virginia senator Joe Manchin and Indiana senator Dan Coats, that would extend the deadline to five years. But even that merely delays the larger problem: The technology in question is prohibitively expensive.

In its press statement responding to the MATS rule in December 2011, the United Mine Workers predicted that “this rule will put more than 50,000 jobs in the utility, coal and transportation industries at risk, and threatens tens of thousands more in supporting and dependent industries.”

But in March 2012, the EPA went further, proposing New Source Performance Standards (NSPS), aimed at reducing greenhouse emissions from coal-fired power plants. As the UMWA pointed out, “The proposed standards depart from more than 40 years of EPA regulation of fossil fuel emissions by lumping natural gas and coal plants into one category, subject to a single performance standard.” Coal plants “could meet the standard only if they employ expensive carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology.”

Hand it to the president: He’s doing just what he promised. The White House’s energy policy webpage touts a “Clean Energy Standard” that would reduce greenhouse emissions using “a wide variety of clean energy sources, including renewable energy sources like wind, solar, biomass, and hydropower; nuclear power; efficient natural gas; and coal with carbon capture utilization and sequestration” (emphasis added).

Of the three available types of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology in use today, Rajesh Pawar of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico reports that most plants would incur a cost of $50 per metric ton stored. For many coal-fired plants, that would raise the cost of one megawatt-hour of electricity from $63 to $103 or more.

The expense is causing several companies to power down. GenOn Energy, Inc., plans to shut down seven coal-fired plants (five in Pennsylvania, two in Ohio) by May 2015 “because forecasted returns on investments necessary to comply with environmental regulations are insufficient.” Edison International is shutting down two Chicago-area plants, and will likely shut down another in Waukegan, Ill. And, of course, there are others.

CCS is an important step toward “clean coal”—coal produced with minimal gaseous emissions—but “Let’s do it smartly,” Smith says. “Let’s do it in a way that doesn’t wipe out industries.”

Meanwhile, heavily Democratic environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, are waging anti-coal campaigns. The Sierra Club launched a “Coal Is Not the Answer” campaign, and the organization’s Global Warming and Energy Program chief has said, “There is no such thing as ‘clean coal’ and there never will be. It’s an oxymoron.”

For the Obama administration and Democrats in coal-rich locations, balancing the interests of environmental groups and mining interests—and their labor unions—is proving a challenge. And the inability to negotiate that balance may have significant consequences for November’s elections.

President Obama and Mitt Romney are both focusing attention on Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia: three crucial swing states—they have 51 electoral votes between them—with substantial coal industries. In 2008 President Obama defeated John McCain by 4 percentage points in Ohio and 6.3 percentage points in Virginia; he took Pennsylvania by 10.4. However, after three-and-a-half years of 8 percent unemployment and a barrage of assaults on the coal industry, each could potentially swing to the right—particularly Ohio, which went for Bush in 2000 and 2004, and Virginia, which, before 2008, had voted for the Republican candidate in every cycle since 1968.

Ohio may be only the tenth-largest coal producer in the country, but it is still a $1.1 billion industry in the Buckeye state. When Vice President Biden visited Martins Ferry (pop: 6,600) to campaign in May, coal miners joined local Tea Party activists to protest, waving signs declaring, “Stop the war on coal, fire Obama,” and “Coal keeps the lights ON!”—which, in Ohio, is true: 86 percent of the state’s electricity comes from coal.

Coal has become a central issue in the state’s Senate campaign, which pits state treasurer Josh Mandel against incumbent senator Sherrod Brown. In March Brown voted against an amendment that would have nullified MATS, and Mandel has used Brown’s anti-coal vote to highlight the link between energy and jobs in Ohio. At a campaign stop in the eastern part of the state in May, accompanied by local coal miners, Mandel said, “We need to get the Sherrod Brown/Barack Obama EPA off the backs of the coal industry so the folks in east Ohio can keep their coal jobs.” And in early July, at a campaign stop at Franciscan University, Mandel warned that “The Sherrod Browns of the world . . . the Barack Obamas, and the Hollywood elites of the world who are trying to block coal mining, and block oil and gas exploration: They’re not only on the wrong side of the issue, they are also on the wrong side of history.” The most recent polling averages show Mandel only three points behind his opponent.

In Pennsylvania, miner-turned-owner Tom Smith is the Republican nominee to unseat incumbent Democratic senator Bob Casey in Pennsylvania. Reacting to the state’s GenOn power plant closures, Smith said, “President Obama favors the appeasement of his most liberal special interest allies over creating jobs in Pennsylvania and providing consumers with affordable energy.”

In Indiana, which also has a substantial coal industry (and is poised to vote Republican after narrowly choosing Obama in 2008), Richard Mourdock, a sixteen-year vice president of Koester Companies’ Indiana coal subsidiary, upset sitting Republican senator Richard (Dick) Lugar to face Democrat Joe Donnelly for the state’s open Senate seat. Mourdock tells The College Fix that the coal industry supports him “overwhelmingly” because “they know what’s at stake.” “They are scared to death,” he says. They know that “a vote for my opponent would in effect be a vote for Harry Reid,” and that would be “disastrous.” He notes that the industry’s leaders were among his first supporters during his primary challenge, and they have been some of his most generous backers.

Virginia, which bucked its electoral history and voted Democrat for the first time in nearly a half century in 2008, has 32,000 jobs tied to coal, accounting for more than $2.5 billion in wages. Virginia’s Democratic senators, Jim Webb and Mark Warner, crossed party lines to vote against EPA emission rules in June—rules that Republicans contend will cost consumers $10 billion and kill 50,000 jobs. Although the measure failed, and the rules were upheld, Warner and Webb have shown pro-coal inclinations. They have appeared at industry rallies and in early 2011 co-sponsored a bill similar to Manchin-Coats that would delay EPA greenhouse gas regulations two extra years “to protect jobs and coal and manufacturing industries.”

The position comes with risks for Virginia’s senators. Supporting the coal industry threatens to alienate environmental groups and proponents of alternative energy sources. And that is the case nationally. As UMWA president Cecil Roberts said in April on CNBC, there are “environmentalists in all 50 states,” but coal workers in just a few.

Phil Smith does not anticipate that the UMWA will endorse either presidential candidate (it endorsed Obama in 2008), and several coal unions have decided to sit out the presidential election altogether. They will participate in other races, at the state and local levels, but when it comes to backing the president, what support existed in 2008 has largely evaporated.

Roberts says the Obama administration has become “tone-deaf . . . when dealing with issues that will [a]ffect coal miners, their families and their communities.” But the evidence of four years points not to tone-deafness but to an orchestrated antagonism to the interests of the coal industry—and the people whose livelihoods depend on it. What does Roberts expect will be left of the coal industry at the end of a second Obama term?

Fix contributor Ian Tuttle attends St. John’s College.

Like The College Fix on Facebook.

IMAGE: Jack Corn/flickr

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.