It was a late night in Madison, Wisconsin, a city known for the party-hard nature of its college students. A friend and I were returning to my apartment after partaking in some mild revelry across town.

I live on the fourth floor of an industrial-style building. My apartment is across from a stairwell at the end of a long, L-shaped hallway.

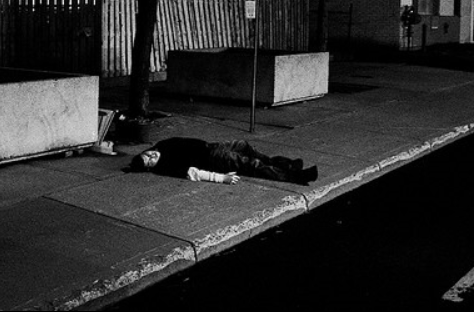

After turning the corner in the hallway, my friend and I saw in the distance what looked like a person lying on the ground. As we continued walking, gradually closing in on our destination, we realized that there was, in fact, a person on the floor. He was unanimated. Something was clearly wrong.

My companion is educated in the health sciences, and she was able to assess the situation much better than I. She knelt down next to the man, who must have been trying to enter stairwell only to literally fall short of his objective. Notwithstanding her tapping on his chest and shouting in his ear, he remained unresponsive. Questioning ever more basic tenets of anatomical existence, she felt his pulse. He was breathing.

That the ground-dweller was a college student was obvious, and he appeared to be roughly twenty years old. On this night, his misfortune was likely the result of a miscalculated affair with Lady Libation.

My friend made a 911 call to summon a medical professional. The dispatcher asked her a long series of questions to determine where she was, what the situation was, how old the man was, how much he weighed, whether or not he was breathing, etc.

Within a few minutes, an ambulance arrived. Because of what my friend revealed over the phone, the ambulance was accompanied by a squad car.

In tandem, paramedics and uniformed police officers revived the man. Ultimately it took some intense shaking and shouting to return him to a state of consciousness. They then proceeded to question him.

All of his responses were muddled in tone and nearly incoherent. They asked him what the date was, to which he replied, “two-thousand-nineteen-ninety-nine.” They asked him where he was and where he needed to go. His answers were as pathetic as they were hilarious.

Eventually it was determined that he lived in one of the dormitories on campus. Since he was clearly underage, they took him into custody and escorted him off the premises.

That’s when the questions started—not questions from the police, but questions of conscience. My friend seemed guilt-ridden and very unsure about what we had just done. Should we have called 911 and therefore the police? What if we ruined the rest of the young man’s life?

While maybe hyperbolic, there is a point there. What if that citation injured his relationship with his parents? What if that contentious relationship snowballed into him dropping out of school? What if he then became an unproductive member of society living in squalor, and so on and so forth?

This ethical conundrum is a symptom of our government as we have come to accept it and of what we have allowed it to become. Medical help for someone in need is, in many cases, unattainable without police involvement.

Clearly, the young man behaved idiotically the evening he became a denizen of my corridor. But his crime had no victims. His biggest offense was his lack of one additional revolution around the sun. Yet the potential negative effects of what happened in that stairwell are much larger than a fine.

What should a libertarian—nay, a decent human being—do in that situation? Should you do everything in your power to avoid intrusion from government? Should you do everything in your power to handle the situation yourself?

In retrospect, I would have looked into the young man’s pocket, pulled out his phone, and accessed his most recent call. I would have made that call again, identified who he was, and figured out where he needed to go. I would have gotten somebody to pick him up or I would have taken him myself. I would not have called an ambulance or the police unless death was imminent.

It is troubling to know that by attempting to help someone, you may inadvertently cause harm. Many consequences—such as unnecessary police involvement—are predictable, and should be avoided. The plausibility of unintended consequences should be constantly considered.

Fix contributor Joseph S. Diedrich is a student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is also Director of Operations of Young Americans for Liberty at UW, and a columnist for Washington Times Communities.

Click here to Like The College Fix on Facebook / Click here for @Twitter

IMAGE: Alex Cairncross/Flickr

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.