UPDATED

You could not ask for a more glaring contrast between campus and criminal justice measures of acceptable sexual behavior than those revealed by the recent trial of Yale student Saifullah Khan.

I should know: I sat through the entire seven-day trial because Khan’s parents were not able; as a mother myself, I could not imagine my child enduring such a terrifying experience alone.

As co-president of Families Advocating for Campus Equality, a nonprofit that supports students accused of sexual misconduct on campus, I have met hundreds of students like Khan, caught up in a political and ideological tidal wave leaving devastation in its wake.

In October 2015, Yale suspended Khan with no investigation based on a sexual-assault allegation. Last week a New Haven Superior Court jury acquitted Khan of all charges, taking less than four hours to agree unanimously that his accuser was not credible and there was insufficient evidence to support her accusations.

Meanwhile, Yale students stunned by the verdict are convinced Khan is guilty, vilify him in articles and online posts, and protest his return to Yale’s campus.

While no one denies sexual assault is a perverse and heinous crime, campus ideology has turned a “nine-second stare” and “unwanted touching” into expulsion-worthy behavior. It also, as in Khan’s case, demands “victims” be believed.

Much of the reporting on the Khan trial has consistently omitted details pivotal to the jury’s findings. I assume this is to appease those espousing the sentiment that victims never lie and the court system is rigged against them. But the truth is the truth, and I refuse to be intimidated into silence by mob mentality.

Here’s what the media and “believe the survivor” activists do not want you to know.

The truth, and nothing but the truth

Khan was born in a refugee camp in Afghanistan. He was invited to the United States when he was identified as gifted and offered a full ride to Yale, conditioned upon his gap-year attendance at The Hotchkiss School.

The gap year was intended to acclimate him to an environment vastly different from his own, in which he had never even used a knife and fork. He wrote about his uncle’s murder in a Taliban mosque bombing for the Yale Daily News.

To circumvent the obstacle of a well-documented friendly and even flirty relationship between Khan and his accuser, the prosecution tried to use his intelligence against him.

Also a senior at Yale on that Halloween night, the accuser appeared conservatively dressed with little or no makeup, dark circles under her eyes, and barely combed long wavy hair. I had to admit, she did look like a victim.

In his direct examination, the prosecutor led the accuser through the chronology of events, beginning with Khan’s attempt to “friend” her on Facebook before they’d met. The accuser said she “deleted” Khan from her account only to discover Khan attempt to “friend” her a second time.

The accuser and Khan met at a lecture, and two weeks later, on Oct. 26, Khan texted the accuser and invited her to dine with him on Halloween. Despite previously rejecting Khan’s Facebook-friending attempts, within minutes the accuser enthusiastically replied “sure!”

It quickly became apparent the prosecution’s case was predicated on the theory that Khan was a brilliant and manipulative stalker who carefully “groomed” his victim, then shrewdly isolated her from friends to consummate his premeditated sexual assault.

If this sounds familiar, Occidental College used a variation of this theory – good grades and good family – to profile an accused student as a rapist. His lawsuit against the college continues four years later. Brown University also lost a due process suit in 2016 because it found the accused responsible for “manipulation,” which didn’t exist in its policy at the time.

The prosecution often alluded to the fact that Khan played online strategy games and was majoring in cognitive science, betraying an erroneous assumption that cognitive science involved mind control. Jurors didn’t buy it and neither did I.

After a chance Oct. 29 encounter, the accuser and Khan had lunch. She said he bragged about his “position of power on campus” and having helped create the popular student Facebook page Overheard at Yale. She continued to reach out to Khan over the next two days, while later testifying he was stalking her.

The accuser said Khan insisted on accompanying her after lunch, but she allowed him to help her with physics, a subject she found difficult. She said he followed her back to her room and became “noticeably frustrated” when asked to leave. Not only did this manipulative-stalker characterization ring false to those of us who knew him, but Khan testified he needed to rush off to grade papers for a class he was student-teaching.

Khan’s alleged aggressive stalker behavior didn’t stop the accuser from sending him a playful text message later that day referring to her earlier prediction of rain. She texted him again that evening to accept his offer of a ticket to the sold-out Halloween concert by the Yale Symphony Orchestra. The annual performance (below) includes an original silent film performed by members against a backdrop of movie soundtracks and pop music.

I excused her seemingly irreconcilable conduct by assuming she desperately wanted to attend the show, but I still wondered why her text conversations with Khan were continually peppered with giggling and smiling emoticons and highlighted by exclamation points. On the stand, the accuser explained her texts are commonly “very emotive,” and insisted this was merely a “business transaction.” Maybe, I thought.

The accuser’s behavior the following day was even more puzzling. First, she initiated yet another text conversation with Khan, asking if he was going to “assert [his] authority” concerning a critical post on Overheard at Yale. As if that weren’t enough to question her purported fear of Khan, I was stunned to learn she followed her initial text with the romantic Shakespeare Sonnet #1, then tried to convince the jury she had not read the sonnet before sending. It begins “From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby beauty’s rose might never die …”

Khan and the accuser discovered they shared something unexpected: a Jewish connection. The accuser learned at dinner on Halloween that, despite his Muslim heritage, Khan belonged to the Jewish Shabtai society and would be helping set up its party, one of many alcohol fueled “pre-game” parties on campus that Halloween.

The accuser herself is a Jewish immigrant from central Asia but did not belong to Shabtai. She claimed Khan had joined Shabtai due to the “power” it conferred. He had a different explanation: Shabtai was the only place he felt welcomed on Yale’s campus.

Accuser’s performance ‘worthy of an Oscar’

The testimony of the accuser and prosecution witnesses about her intoxication level that night, contrasted with basic science and others’ observations, was puzzling. Like one of the jurors with whom I spoke, I could not “fathom” why the state had pursued the case when there was no testimony or other evidence the accuser had been assaulted.

The accuser testified she did not eat much dinner, but Khan recalled she’d eaten chicken, broccoli and pumpkin pie, the latter served especially for Halloween.

Student ID card activations called into question the accuser’s narrative that Khan forced himself into her dorm room after dinner, became angry when she asked him to leave, and “crossed a boundary.” Khan’s ID card actually swiped into his dorm entry seven seconds after she swiped into her own, making the accuser’s version impossible. (ID cards can open any entry door, but not other students’ individual room doors behind the entries.) Khan said the accuser invited him in to see her costume, but he declined in order to set up for the Shabtai party.

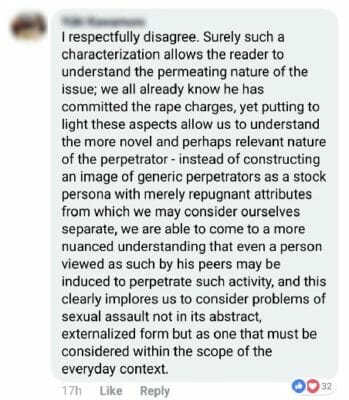

The accuser maintained throughout the trial that she was in and out of consciousness during the alleged assault, her memories were “fragmented,” she was “traumatized” and “in a state of shock.” Typical victim advocate terminology, I noted. (at left, example of typical Yale student mindset from Overheard at Yale)

The accuser maintained throughout the trial that she was in and out of consciousness during the alleged assault, her memories were “fragmented,” she was “traumatized” and “in a state of shock.” Typical victim advocate terminology, I noted. (at left, example of typical Yale student mindset from Overheard at Yale)

When the defense attorney pressed the accuser on what she did recall, she either cried, increasingly claimed not to understand the question, or asked that it be repeated. One juror told me her performance was “worthy of an Oscar.”

Because of the implication that the accuser’s memory loss was due to extreme intoxication, I was curious how much alcohol she had consumed during her two hours at the Shabtai party.

After I saw the approximately 6-ounce plastic cups used at the party – neither the accuser nor her witness could identify the exact cup – I calculated it would be generous to conclude the accuser had consumed 10 to 12 ounces of alcohol of varying potencies over that two-hour period. She herself had testified the drinks were poured “two fingers high.” Was that enough for her to be in and out of consciousness for the next four to five hours?

Prosecution witness Richard Gaylor testified the accuser was a “four” on an intoxication scale of 10 when she and her friends left Shabtai to walk to the symphony show. In contrast, Tabitha Spencer-Salmon testified her friend was “above a 10” when they reached the hall.

Pressed on why, as a trained emergency medical technician, Spencer-Salmon did not seek medical assistance for someone whose intoxication was cranked up to over 10, Spencer-Salmon incongruously claimed the accuser “appeared oriented to time and place,” and thus not sufficiently intoxicated to raise concern. I disregarded Spencer-Salmon’s testimony after that, and assumed the jury did as well.

The accuser’s penchant for vomiting that night was not the silver bullet the prosecution thought. No one disputed she threw up while sitting in the concert audience, or that afterwards Khan escorted her to the restroom.

The jury concluded the grainy, choppy videos of the couple’s walk from the concert hall to their dorm did not show, as the prosecutor continually insisted, Khan supporting the accuser, with her feet dragging and her eyes closed.

I have spoken to two jurors who said they watched the video several times in deliberations and did not see the accuser stumbling, but saw her walking with Khan, smiling. One said her “body language and expression on her face was nothing but willing …” It unsettled me that a prosecutor would attempt to convince a jury to see something that was just not there.

https://twitter.com/PercivalDalen/status/971487794743820288?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

ID card records are inconvenient for prosecution

Also just not there: any evidence that Khan forced himself into the accuser’s room after the concert. Forty-two seconds elapsed between Khan opening the entry door to the accuser’s dorm and opening his own entry door. Another 25 seconds elapsed between his room swipe and a second swipe into the accuser’s entry; Khan said he opened her door for her and came back when she called out for him.

Khan’s ID card records also bolstered his testimony that the accuser asked him to check on her friend Keni Sabath. He entered Sabath’s entry door only 11 minutes after he’d last entered the accuser’s; over the next 25 minutes or so, his card was swiped into Sabath’s entry, his own and back to the accuser’s entry.

I wondered, why did the accuser let Khan back into her room if she was afraid of him? She claimed at the concert Khan had taken control of her iPhone and the metal key to her dorm room, but the jury didn’t believe it. And don’t dorm rooms have dead bolts that lock from the inside?

After failing to find her friend Sabath, Khan said he returned to the accuser’s room. She sat on his lap, started kissing him and asked what he’d like her to do sexually. The accuser agreed to perform oral sex if he wore a condom. She gagged and threw up, which Khan believed was from performing oral sex, not intoxication.

He suggested she take a shower, and believing “the night was over,” sat on the accuser’s sofa and telephoned his long-term girlfriend, with whom evidence shows he spoke for three hours. Though Khan demonstrated lack of sensitivity by making the call there, this was clearly not criminal behavior.

After his phone died, Khan claimed the accuser invited him into her bed and, using a second condom, they had consensual sex. She found him on her sofa the next morning and slapped him, but also said she was embarrassed and, according to Khan, asked him not to tell her friends.

The portrayal of Khan as a calculating rapist contrasted, once again, with digital evidence. She responded to his 6:14 a.m. text with “LOL,” he replied with a winking emoticon and she replied “Go to sleep this will stay between us that goes for you too.” The first indication she was upset came later that day, when she texted him “you’re a piece of shit.”

Asked why she told a Yale Health Center nurse she had consensual sex with a regular partner when requesting Plan B, the accuser said she was “too traumatized” to tell the nurse of the assault, her memories were “fragmented” and she was “in shock.”

Khan’s failure to remove the used condoms from the accuser’s room didn’t fit the prosecution’s portrayal of him, and, in the end, the prosecution’s decision to introduce results of the sexual-assault exam backfired when the defense attorney elicited from the prosecution’s expert witness that the accuser’s anal swab revealed another male’s DNA.

Everyone, even the jury and prosecutor, seemed stunned by this revelation. It was difficult to reconcile with the prosecution’s depiction of the accuser as a victim of a “heinous crime” who had not had sex for six months.

His ‘trial’ continues out of court

When Khan finally took the witness stand on the last full day of his trial, it seemed as though jurors were anxious to hear his story.

Expressionless during most of the trial, they appeared to listen intently as Khan answered questions clearly, always with a “no sir,” or “yes sir.” Though the prosecutor tried to badger Khan to the point that the judge finally admonished him, Khan’s testimony remained unhesitating and direct.

Now he’ll have to do it all over again in a Title IX proceeding. Yale’s prior behavior suggests Khan will get the traditional kangaroo court, without the harsh glare of the public to correct the bias and incompetence of Yale and its police department.

It’s worth recalling that on the morning of the first trial scheduled in October, the prosecution produced a literal garbage bag of “forgotten” or previously misplaced evidence, delaying the trial several months.

More documents suddenly appeared during the trial, which ended last week, some of them exculpatory. The last batch came with the explanation that Yale officials thought they were confidential. Written documents shown in Yale Police Department video interviews have never been located and presumably have been destroyed.

Khan won’t have the benefit of a different generation of citizens who aren’t blinded by “believe the survivor” ideology to judge his fate in the Yale proceeding, either.

A staffer at the Yale Daily News told me about the student blowback the paper faced after running a profile on Khan that quoted his friends saying positive things about him. The original headline on the story, “Khan was known as charming, ambitious,” was within hours qualified by the addition “but dogged by allegations.” A commenter claimed the paper didn’t tell readers about the headline change for several hours.

The News still has not told readers that it deleted the web address for the original article – apparently because it includes the original headline. That address now redirects to the newer one.

In contrast to the uproar on Yale’s campus, none of the jurors with whom I spoke felt the accuser’s testimony was credible, and alternate juror Elise Wiener attributed her recollections to “false memories.”

Juror James Galullo told The New York Times “he did not understand the outrage that the verdict had inspired on campus, among students who wrote angry opinion pieces for the campus newspaper or took to social media to denounce the outcome.”

He explained that because “[t]he jurors were all basically middle-aged,” they could “see their way through all the noise.”

Noise, indeed. It is likely Khan will hear a lot more noise before his ordeal is over.

Cynthia Garrett is co-president of Families Advocating for Campus Equality.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The College Fix is not identifying Saifullah Khan’s accuser, who is named in public court documents, at his request.

UPDATE: The Fix has removed the name of a juror who claims to have been speaking to Garrett off the record. The number of seconds between Khan swiping into his dorm entry and the accuser swiping into her own has also been corrected.

MORE: Trial reveals Yale Police Department misconduct against accused student

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.