‘Cracks in the Ivory Tower’ by Jason Brennan and Phillip Magness

What colleges market to prospective students: a life-changing, eye-opening, “transformative” experience across four years on campus.

What they actually provide: useless courses that reward crusading professors, low academic standards that free up time for rock-star researchers, and self-perpetuating bureaucracies whose solutions to problems are invariably … more problems.

Much of this, of course, is funded by taxpayers.

Scholars Jason Brennan and Phillip Magness identify the very human problems in modern higher ed and offer solutions in their new book, “Cracks in the Ivory Tower: The Moral Mess of Higher Education.”

The book provides an in-depth look at the pitfalls of college spending, how officials justify the expense, and the key players behind the “moral mess” that has emerged in recent decades.

The authors are interested in the “incentives and constraints” that students, faculty and administrators face, and more specifically how incentives are exploited across the board.

Philosopher and political scientist Brennan is a professor at Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business. Magness is a senior fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research and former professor of history and economics at George Mason University.

Forced to imbibe social-justice ideology in the ‘Gen Ed Hustle’

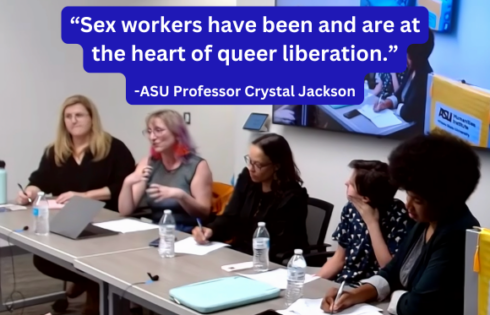

In the chapter “When Moral Language Disguises Self-Interest,” the authors expose the “hidden motives” beneath the progressive ideals that some professors convey to their students through the curriculum.

By accusing their own institutions of moral failings, particularly their histories of exploitation and marginalization, faculty can boost their own ideological and economic fortunes. The book lays out the faculty argument:

Our college/university is systematically racist, heteronormative, classist and sexist. The best way to start down the long road to fixing these problems would be to increase my department’s budget, promote me, let me hire my friends, let me fire my enemies, require that students take my classes, require faculty to push my ideology, make my ideology part of first-year orientation, and give me power over other academic departments. That wouldn’t solve our problems, but it sure would help.

To protect their departments from the financial ramifications of low enrollment, faculty push to get their courses classified as “gen-eds.” Such classification effectively means guaranteed enrollment and more money for the department.

MORE: UMass-Boston hosts weeklong event on social justice

This system requires students to enroll in courses that are unrelated to their major simply to fulfill general-education requirements, an arrangement Magness and Brennan call the “Gen Ed Hustle.”

Undergraduates are already at an age where they are easily influenced or cajoled into political ideologies, and professors exploit this phenomenon accordingly.

“Once you start requiring students to take classes for their own good, you thereby create a system where professors can lobby to take talents for the good of the professors,” the authors write. Students then become “pawns” of professors who simply try to enlarge their own social-justice fiefdoms.

Students are disinclined to fight this system because they see it as an inevitable exercise in box-checking. They will check any box to attain their degree, and will enroll as they are told.

‘Implicit bargain’: Professors enjoy sabbatical while students slack

Professors don’t only use the system to further their ideologies and guarantee plum jobs for themselves and their allies.

They also use it to survive the Darwinian struggle at the heart of elite academia: “publish or perish.”

Tenured faculty put the education of pupils second to the outside academic research that offers lucrative opportunities for both themselves and the university. The more prominent professors at any given campus spend little time in the classroom and may spend semesters on sabbatical.

As a result, contemporary college students are often taught by adjunct professors or graduate students, paying for an education that differs greatly from how it is marketed.

This inattention to student performance by elite professors incentivizes rampant cheating among students, Magness and Brennan argue. They cite statistics that find today’s students spend less time on academics than they do on leisurely, socially-centered activities.

MORE: Grades are up, studying is down. Is college too easy?

In the 1960s, students spent an average of 40 hours a week on academics. That has fallen by a third, to just 27 hours.

“One reason they work less is that faculty assign less work. Since the 1960’s, faculty have been assigning fewer pages of reading and shorter essays,” the authors write. “Every hour spent studying is not an hour spent playing video games… partying, or hooking up.”

This dynamic is an “implicit bargain” between faculty and students, in which neither asks a great deal of the other. “This arrangement benefits both sides– the faculty publish while the students play.”

To put it in familial terms, this bargain is like a father letting his kids run wild while he’s engaged in supposedly more important endeavors at work.

Goading less qualified students to apply so they can be denied

American higher education is broken as a business model as well as a pedagogical endeavor, the authors argue.

Its chronic illnesses include misleading students through unethical advertising tactics by administrators, who are held to a lower marketing standard than other businesses.

While colleges promote the cliche that the four-year experience will uniquely transform a young person’s life, in reality, young adults are already going through an array of characteristic changes regardless of where they end up.

Unlike other businesses, colleges are in the clear to say almost anything to lure prospects in. They have no risk and every reward to admit a large demographic of students who pay for their educations with federal loans: Even if the student drops out, the college will still cash out because the student must repay the government.

Colleges can get away with this game because the results they deliver – student success rates – are entirely subjective, contrary to businesses that must deliver tangible results for their investors.

MORE: ‘Universities increasingly lie and cheat’ because they get away with it

The authors identify another example of unethical business in university advertising: The overarching messages cajole students into applying to the most selective schools in the country, even if they are unqualified economically or intellectually.

These schools are essentially tricking students into applying solely to reject them as applicants. The practice lowers the schools’ acceptance rate and thus boost their selectivity to ever greater heights.

The situation would be very different if colleges were required to offer disclaimers to prospective students so they know the real risks of going to college, as recently argued by Ohio University economist Richard Vedder in a Forbes column that touches on the book by Magness and Brennan.

The message they promote – the “relatively risk-free path to a prosperous life” – stands in contrast to objective data such as their dropout rates, how many freshmen continue as sophomores, and the “underemployment” rate among graduates, Vedder wrote.

“Perhaps penalties for collegiate moral transgressions need to rise” so that colleges “serve society” as opposed to their own “narrow parochial interests,” he concluded.

The prestige (and salaries) of top administrative jobs

If and when students arrive at a certain college, they are likely to find a notable absence of cost/benefit analysis in administrative spending. Some prime examples are the funding of leisure-oriented spaces on campus, such lazy rivers and rock climbing walls, and diversity-oriented programming.

Though these millions of dollars in questionable outlays are not the main reason why college has become so expensive, the authors note, they do not improve the educational experience at the heart of college.

For example, the University of California System and University of North Carolina-Wilmington have been criticized for cutting corners in science departments to further fund diversity efforts.

Rather than allowing the best possible decisions for students to dictate spending, college bureaucracies just hire more people to justify an increase in their yearly fiscal budgets.

For the past 40 years, they’ve been hiring at a breakneck pace: a 300 percent increase in administrative and non-teaching staff members across the American higher education system.

The skyrocketing salaries of administrators are also responsible for the increasing price tag of college. There is a distinct difference between the average professor and administrator, and it’s measured in glamor and dollar signs.

Although high-ranking positions are almost always filled by former faculty who “made the jump,” those who apply to be university president, provost and dean are “drawn to the prestige of the position, or its accompanying salary,” Magness and Brennan write.

Even hiring two to three administrators will cost around $250,000, and that is “money not spent giving a poor or gifted student a full ride.”

MORE: Study finds diversity bureaucrats don’t improve campus diversity

IMAGE: Oxford University Press

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.