Everyone is psychologically fragile and needs protection from words and ideas.

Everyone should trust their emotional response or think with emotions instead of reason.

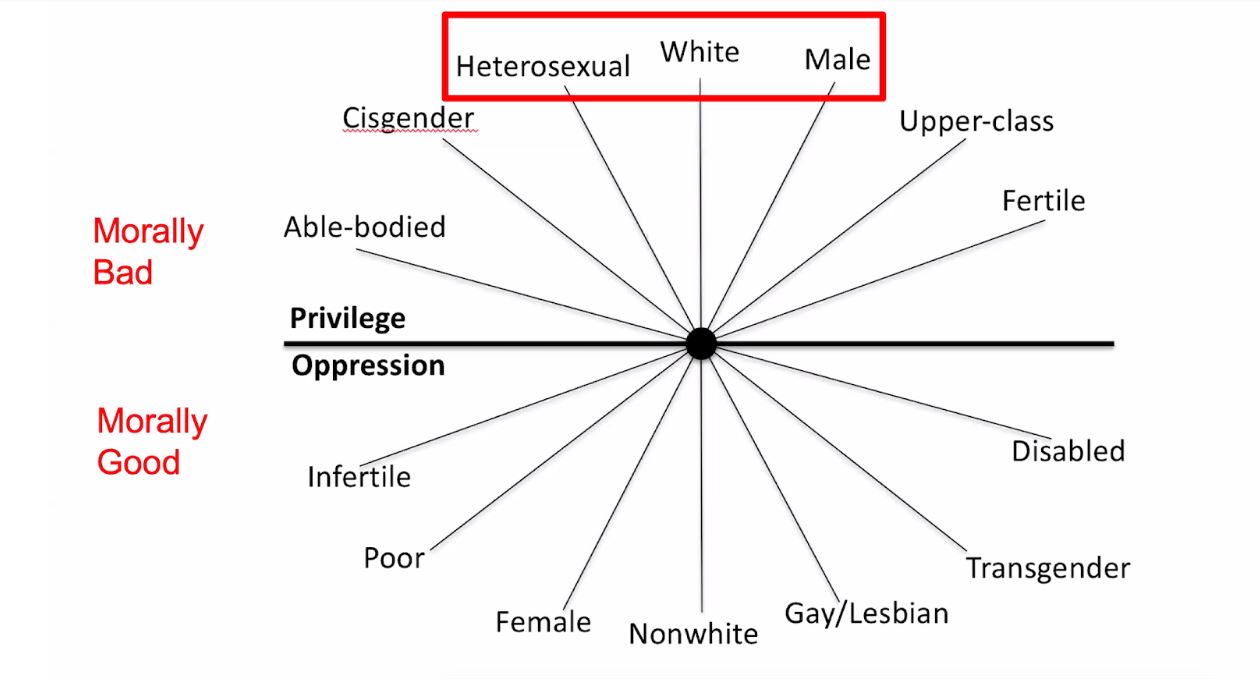

Everyone is morally good or morally bad based on their race, gender, social or economic status.

These are three ideas upheld at most universities — and they’re horrible.

So says renowned social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, a professor at the New York University Stern School of Business, who recently explained how many universities promulgate these three ideas to consequentially bad results.

They are “so bad,” he told a group of students, “that if you believe all three of them, I can almost guarantee you will be a failure in life. … They’re the opposite of deep psychological truths.”

Haidt’s comments were part of a talk hosted by the Tikvah Fund as part of its online townhall series on higher education. Haidt, co-author of the book “The Coddling of the American Mind,” explained why the ideas are faulty during the 90-minute virtual event May 20.

Addressing the notion that students need protection from words and ideas, he said it’s a direct contradiction to Friedrich Nietzsche’s dictum “what doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.” Today, he said the concept pushed on campus is “what doesn’t kill me makes me weaker.”

“There emerged a kind of a new culture on many college campuses, especially elite institutions in the Northeast and the West Coast, with a set of concepts around safe spaces, trigger warnings, microaggressions, bias response teams, speech is violence, a tendency to see everything as power structures and matrices of oppression,” Haidt said.

“In such an institution, you develop a ‘call-out culture’ and students at some of the safest and most welcoming places in America, some of them, began to speak as though they are fragile people living in a dangerous or hostile university and therefore need protection from words, books and speakers,” he said.

By training students to look for microaggressions, university leaders teach students to ignore real intent and essentially are saying “if in doubt, interpret it as an intentional attack,” he said.

“We teach them emotional reasoning,” the professor said. “If you feel offended, don’t question whether you might have gotten it wrong. An offense has occurred and someone, an administrator, now needs to be brought in to do something.”

Universities have essentially encouraged students to “engage in fortune telling” by allowing the assumption that people are “fragile” and therefore need “trigger warnings — not exposure as most psychologists would advise.”

Underscoring all this is the bad idea “life is a battle between good people and bad people,” he said.

Universities now teach students to see society and people in terms of different social categorizations, such as race, gender, class and sexuality, and to see some of these categorizations as inherently good and the others as inherently evil, he said.

The professor, using the graph (pictured), said part of the problem is that students are taught some people are morally bad because they are privileged and therefore oppressive, and others are morally good because they are oppressed.

“What happens when you say, ‘You know what? The cause of our problems is overwhelmingly the intersectional address of heterosexual white males, they’re the bad people, they’re the ones who cause the problem and we have to all unite against them,’” he said. “That ends up being the on-ground implication of the way intersectionality tends to play out on campus—at least as far as I have seen.”

MORE: Study finds need for intellectual diversity in psychological sciences

IMAGE: Locke Photography / Shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.