Creation of ‘synthetic’ embryos raises questions about human value

International ethicists are debating calls this fall to loosen a 14-day limit on human embryo research in Canada and the United Kingdom, with an eye toward the United States as well.

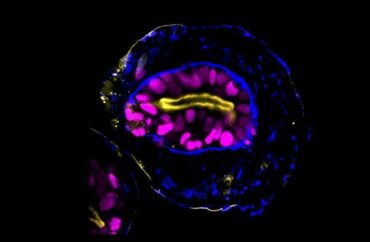

A series of recent events, including the creation of “synthetic” embryos at the University of Cambridge, as well as research showing public support for the change, are among the things prompting renewed attention to the limit.

Two scientific research leaders with the Charlotte Lozier Institute, a pro-life scientific organization in America, told The College Fix that synthetic embryos are human beings, even though they are created through a synthetic process without a male sperm or female egg.

“These human beings are conceived from clonal cell lines, so they are clones, being genetically identical,” CLI Vice Presidents Tara Sander Lee and David Prentice told The Fix.

“Human beings conceived by scientific bioengineering are no less human than those conceived by natural processes,” they said. “Therefore, they have the same moral significance; and they require the same bioethics considerations before use for biomedical experimentation.”

Professor Francoise Baylis, a bioethicist at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, disagreed.

Currently, synthetic embryos cannot develop into living, born human beings, Baylis said. Therefore, a synthetic human embryo “is the moral equivalent of the non-viable natural human embryo,” she told The Fix.

“In my estimation, neither has moral status,” Baylis said.

Baylis said ethical considerations could change “if the synthetic embryo one day had the potential to become one of us.”

International laws

In Canada and England, laws prohibit research on human embryos after 14 days of life. These regulations stem from the 1990s when lawmakers desired to advance scientific research while not crossing certain ethical boundaries that could arise from experimenting on human beings.

The United States does not have a statutory limit on human embryo research, the Charlotte Lozier Institute researchers told The Fix.

“Scientists in the U.S. follow the 14-day limit as a matter of practice so as not to upset federal regulators and especially funders,” Lee and Prentice said, noting that the country does have limits on public funding for such research.

Human development

After 14 days, the embryo enters “an important developmental stage called gastrulation” in which the foundations of the heart, nervous system, and brain begin to form, Lee and Prentice told The Fix.

Baylis told The Fix that the 14-day mark also is significant because, up to that point, the human embryo is capable of twining and recombining, “when one embryo absorbs another and two embryos become one.”

“Human persons do not have this capacity and some have argued, on biological grounds, that prior to 14 days the human embryo is not protectable human life,” she told The Fix.

Baylis said others argue that the primitive streak – “the precursor to the brain” that typically appears on day 15 of human development – is the “morally relevant biological demarcation line.”

“Both of these claims suggests that moral status is a function of biology. This view is mistaken; recognizing the moral status of another is a value choice,” she told The Fix.

Calls for change

International calls to expand the limit have amplified in recent months, with many pointing to the new developments with synthetic embryos.

Writing at The Conversation earlier this year, Baylis and co-author Jocelyn Downie, a retired Dalhousie medical professor, said loosening the limit in Canada and other countries “could increase our understanding of human development and genetic disorders … and — perhaps — eventually allow for reproduction without using sperm and eggs.”

In England, research on public attitudes, published in October by the Human Developmental Biology Initiative, found most participants supported expanding the 14-day limit as long as strict regulations are put in place, the BBC reported.

What’s more, an editorial in The Economist last month also argued that regulators should lift the “black box” on human development research. Doing so could lead to treatments for congenital heart defects and miscarriages, they wrote.

“The box opens up again after about 28 days, when scientists can study aborted embryos,” the editors wrote. But it is within the “unobserved two-week period that the earliest organs begin to develop,” the editors wrote.

Alternatives

However, Lee and Prentice said researchers do have ethical alternatives that do not involve destroying human life.

They told The Fix that organoids – “microscopic partial organ structures that retain some of the biological and physiological properties of an intact organ” – can be used successfully and do not involve the destruction of human life.

“Organoid constructs have proven successful in modeling complex mechanisms, disease, and early development,” involving the heart, liver, brain, and eyes, they said.

Religious bioethicists have raised concerns about expanding the limit, too.

Father Tad Pacholczyk, director of education at the National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia, pointed The College Fix to an article he wrote in August responding to news about synthetic embryo developments.

“Ethically speaking, a great deal is at stake in these kinds of synthetic embryo experiments that threaten to manipulate and destroy human life,” Pacholczyk wrote at The Catholic Times. “These developmental studies ought to be carried out by studying animal models, carefully avoiding the use of human embryonic stem cells and the production of human embryos.”

MORE: Leading ‘reproductive justice’ professor insists fetal heartbeats do not exist

IMAGE: University of Cambridge

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.