The absurdities of literature departments have become mainstream liberal opinion

When American English departments tossed out the literary canon in the 1980s, they discarded cultural coherence and patriotism and replaced it with the cynicism and cultural nihilism that has taken over the left, emeritus English Professor Mark Bauerlein argued in Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture.

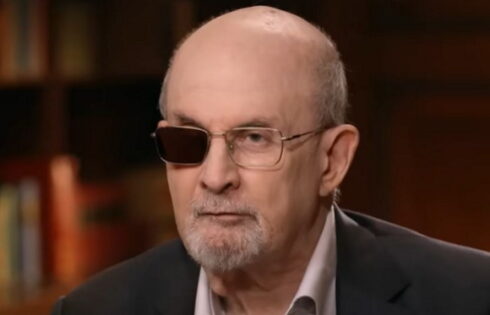

Bauerlein (pictured) narrated the decline of the English major from his last years of graduate school at UCLA, in the late 1980s, when he “believed that English sat at the top of the academic heap.” His department had close to 1,700 majors, each required to take a yearlong survey course that promised “the full sweep” of English, from Beowulf to W. H. Auden.

“I was an obedient liberal at the time who nonetheless favored Great Books and Western Civ,” Bauerlein wrote. He witnessed vital debates between cultural conservatives and liberals over what belonged in the literary canon, academic exchanges that seem “quaint” to him today, because the conservative side lost decades ago.

His liberal colleagues at the time claimed they simply wanted to broaden and diversify the canon, “adding Toni Morrison to Shakespeare, adding wives and mothers to kings and generals in history courses,” Bauerlein said.

But the “canon wars,” as they were called, were “all over and done by the mid-’90s, when the Culture Wars moved on.”

By the 1990s, it was clear to Bauerlein that the left did not want to broaden the Great Books tradition; it wanted to destroy it.

“The tradition had to go, period,” he wrote. “‘Diversity’ was a dodge, a tactic, a temporary step in the discreditation of the old.”

Today, literature departments are a wilderness of “courses straying into identity politics, media, and various agenda-driven critical theories, with some novels and poems serving as pretexts.” There’s no coherent sequence that students must master, no tradition but the rejection of tradition as elitist, racist, sexist, and all the rest.

Students weren’t too interested — the national share of English majors dropped to just 1.9 percent in 2018-19 — but the new character of the departments infiltrated the culture.

What happened on campus, didn’t stay on campus

Bauerlein wrote that initially he and his conservative colleagues were confident that the cultural chaos and identity politics promoted by English professors would stay in college. He was wrong. As Andrew Sullivan wrote for New York magazine in 2018, two years before he resigned for having unacceptable opinions, “We all live on campus now.”

When English professors rejected their own legacy, they opened Pandora’s box, and out came the woke left.

In the last decade, “blather about “capitalism and patriarchy and whiteness” has moved from elite literary circles to the center of woke politics, in the media as well as throughout major institutions from the military to professional science to elementary schools.

Even more, the spirit of destruction, hatred of the past and of our history, has moved into mainstream politics and into the streets. The widespread cancellations and vandalism of recent decades, the revolutionary toppling of statues and monuments, reproduced the English departments’ trashing of the tradition.

President Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan “wouldn’t have offended anyone in 1984,” but by 2016 it meant fascism for many on the left, Bauerlein wrote. Trump’s 2017 Warsaw speech, which “envisioned the Western past in ways that hearkened right back to the Canon Wars,” celebrated Western civilization and was immediately dismissed by many in the press as dangerously right-wing, an “alt-right manifesto” or “white nationalist rhetoric.”

The English department’s culture of repudiation, a wholesale rejection of our artistic inheritance for unforgivable errors, created a loss of meaning that has reverberated through the country:

To cast America First as an Alt-Right insurgence, first one had to dispel the other America, as preserved in Emerson, Hawthorne, Melville, Thoreau, Douglass, Whitman, Dickinson, Twain, Wharton, and so on. The old syllabus showed America had a lineage of American-ness, an exceptional descent, our own to identify and absorb. And by that acknowledgement, the nation was unified, its past stable and coherent—and good. The literary canon authorized it. However much they dreaded 11th-grade English, youths got a sense of their country through Hester Prynne and Huck Finn and Gatsby, Rip van Winkle and the Joads. These literary characters formed what every nation needs: a body of works with a national meaning. Take that away, keep the patrimony from the rising generation, and the nation forms less clearly in their hearts and minds.

“Citizens who have no knowledge of the greatest users of the American language don’t have a deep conception of America itself,” Bauerlein concluded.

When it sold out tradition for empty “diversity,” the culture lost its soul.

IMAGE: CUNY TV/YouTube

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.