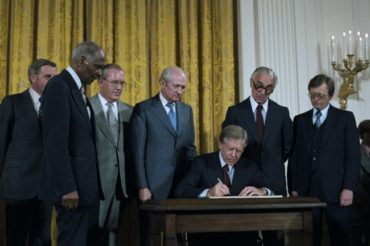

‘Correcting Carter’s mistake’

Forty years to the day after the federal government established the Department of Education, education experts at the Heritage Foundation released a plan to eliminate the entire department.

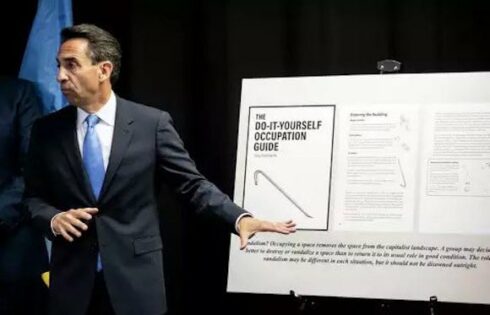

“Correcting Carter’s Mistake: Removing Cabinet Status from the U.S. Department of Education,” was unveiled Monday by authors Lindsey Burke, director of the think tank’s Center for Education Policy, and Jonathan Butcher, a senior policy analyst for the center.

In a webinar on the report Monday, an academic critic of the department’s performance argued that the elimination recommendation was a nonstarter and had never been politically popular.

The Heritage plan calls for the elimination of the Department of Education, which was created in the Carter administration; the transfer of many of its responsibilities to other agencies; and the elimination of some programs entirely.

“The Department of Education has run its course: After 40 years, there is scant evidence that it has benefited American students or used taxpayer money effectively,” according to one of the “key takeaways” from the report.

“As with the Great Society programs of 1965, elevating education to Cabinet-level status in 1980 failed to narrow academic achievement gaps,” it continues. “Devolving the department and housing remaining programs with other agencies would help to restore control of education to states, localities, and families.”

Office for Civil Rights avoids ‘rulemaking requirements’

Joshua Dunn, chair of the political science department at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, and Prof. Martin West of the Harvard Graduate School of Education expressed support for many specific policy proposals within the paper.

West praised the report’s specific policy points to act upon failings within the department. Putting more of the education focus on the state and local level is better than trying to eliminate the department, an idea that has never gained much public support, he said.

Heritage’s Burke noted that President Johnson’s Great Society plan was a first step that ultimately led to the formation of the department. Because the Great Society’s education policy failures led to the department’s creation, this shows that “in government, nothing succeeds as much as failure,” said Dunn of UCCS.

West and Dunn explained what the department can do to work more effectively and avoid becoming a burden on institutions and school districts.

The Office for Civil Rights, which Burke and Butcher propose rolling into the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, has long been a bad actor, according to Dunn.

It tried to “avoid the rulemaking requirements” of the Administrative Procedure Act by using “Dear Colleague” letters to make policy under the guise of “clarifying existing law,” the scholar said, outlining several in the past decade.

Chief among those was the 2011 letter that lowered the standard of evidence for sexual misconduct proceedings. Dunn said this ended up hurting institutions the most by forcing them to either get sued by accused students or face an exhaustive review process from OCR.

Apart from sexual misconduct, Dunn cited a 2014 letter on school discipline that he says ultimately led to classrooms becoming more unruly and harming a teacher’s ability to deal with undisciplined students. That letter pushed schools to use “exclusionary discipline,” namely suspensions and expulsions, as a last resort.

He expressed support for the abolition of the “Dear Colleague” practice of de facto rulemaking. While moving OCR to the Justice Department will not “necessarily make things better,” Dunn is “certain that it cannot make things worse.”

MORE: Lawyers call on Trump to gut federal education mandates on sex, race

Stagnant proficiency rates

In support of the proposal to eliminate the Department of Education, Butcher noted that the measures of student progress have reported little change in academic success in specific subjects since 1970 – a decade before the department’s creation.

While math proficiency has remained stagnant for 50 years, high school graduation rates have actually increased despite students being equally unprepared for college as they were in 1970, he said.

“[C]ollege preparedness and completion data do not demonstrate that more students are ready for postsecondary work,” Butcher and Burke wrote in the paper. “In 2020, the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center found that just 60 percent of college entrants finished their postsecondary studies in six years, never mind four years, with researchers even reporting the percentage of students finishing in eight years.”

The paper notes that 66 percent of students in the University of California System took six years to complete their college education, including 45 percent of students who took “remedial classes in math and reading.”

“Washington has far less information than state and local school leaders, and cannot compare to the expertise that parents have on the needs of their own children,” the paper concludes: “Distant federal policymakers are ill-positioned to design programs and education interventions that are suited to the diverse learning needs of students across the country.”

By “[d]evolving” the remaining programs to other agencies, the department can “make space for a return to education subsidiarity, enabling local actors who are better positioned to determine policies that best meet local needs,” the report says. This will free states and localities “from the strictures of federal mandates, while maintaining key civil rights protections at the federal level.”

MORE: Groups urge DeVos to ignore coronavirus stalling tactics for Title IX reform

IMAGE: National Archives, Karl H. Schumacher

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.