Underrepresented in law schools – and universities increasingly run by lawyers

Christian applicants for positions as law professors may have grounds to sue for “systematic discrimination,” given their “stark” underrepresentation in law schools, according to a study making waves in legal academia.

Northwestern University Law Prof. James Lindgren characterized his study as the first to probe “law professors’ belief in God and attendance at religious services.” It finds that Jews and nonreligious professors are overrepresented in law schools and Catholics and Protestants, underrepresented.

The St. Thomas Law Journal study floats the possibility of a “disparate-impact” case on behalf of religious candidates for law faculty positions, meaning that they face discrimination in practice under facially neutral policies. Lindgren cautions that further research is needed if “intentional discrimination” is to be discovered.

“The Religious Beliefs, Practices, and experiences [sic] of Law Professors” warranted attention from several academics.

Lindgren’s findings “are certainly accurate,” George Dent, who taught law for nearly three decades at Case Western Reserve, told The College Fix in an email. Dent led an effort in 2017 to increase the political diversity in law academia in order to combat the “echo chamber.”

UCLA’s Stephen Bainbridge also recently argued, citing Lindgren’s earlier research, that “religious and political diversity” are “roughly as important” as racial diversity for ensuring viewpoint diversity. The Christian Legal Society did not respond to a Fix request for comment on the study.

MORE: Research finds law schools dominated by Democratic professors

Brian Leiter of the University of Chicago Law School, meanwhile, disputed the import of Lindgren’s conclusions, writing on his blog that more law professors believe in God or a “higher power” than similarly educated academics.

He told The Fix in an email that Lindgren’s comparison of the legal academy and general population is “silly.” Comparing them to even people with graduate and professional degrees is “nonsensical,” Leiter added, citing his 2009 research that found law professors tend to come from elite law schools.

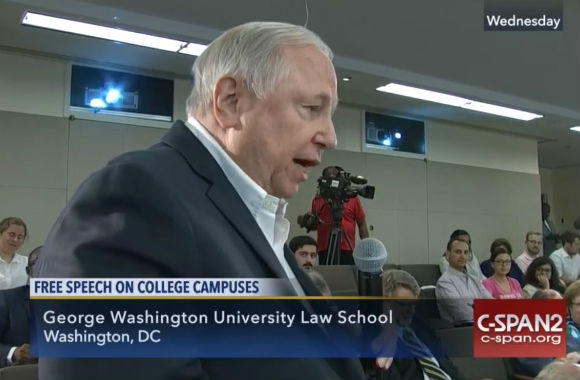

Lindgren’s findings have relevance beyond law schools, George Washington University Law School’s John Banzhaf told The Fix.

He pointed to a Washington Post essay last month that found the number of lawyers tapped to become university presidents has “more than doubled each decade of the last three,” which implies that Christians may also fall out of contention for top university jobs.

Patricia Salkin, provost of the graduate and professional divisions of Touro College, wrote in the essay that 158 lawyers were appointed president just in the past five years. “If the trend continues, in the new decade lawyers may account for 300 to 400 presidents — more than 10 percent of all sitting campus presidents.”

For reference, lawyers “made up less than 1 percent of all presidents during any given decade” from 1900 through 1989, according to Salkin.

Academics ‘despise the beliefs of traditional Christians’

“About two decades ago, I surveyed law faculties at the top one hundred law schools, asking professors about their religious affiliations,” finding that “Christians were represented at only about half their percentages in the larger population,” Lindgren writes.

His new study updates the older one but “probes much deeper, presenting data on belief in God, church attendance, and religiously motivated discrimination.” One of the major changes: “the differences in actually believing in God are much larger than for mere religious affiliation.”

That means law professors are less likely to believe in God than not only the general population but also graduate and professional degree holders. They are more than four times as likely to be atheists and nearly twice as likely to be agnostic than the “highly educated.”

The study sampled from the 2016-2017 Directory of Law Teachers and selected those who matched one of several words or phrases, including variations of “professor” and “chair.” Lindgren (below) excluded those with “adjunct” or “emeritus.”

MORE: Conservative, libertarian law profs demand more politically balanced faculties

Since 1997, Catholics have held relatively steady in their proportion of the law professoriate at 13-14 percent, while Protestants (currently 25 percent) and Jews (20 percent) have each declined about seven percentage points.

Since 1997, Catholics have held relatively steady in their proportion of the law professoriate at 13-14 percent, while Protestants (currently 25 percent) and Jews (20 percent) have each declined about seven percentage points.

This means Protestants are represented at less than half of their share of the general population, while Catholics are represented at less than 60 percent, and both Jews and nonreligious professors are overrepresented.

While every “large ethnic and gender group” in full-time English-speaking law teaching is around parity with each other, Christians and Republicans remain “grossly underrepresented” among large demographics, according to Lindgren.

Whether the underrepresentation results from “disparate impact or overt discrimination is a matter of definition,” Dent told The Fix: “Academics wouldn’t discriminate against a scholar simply because s/he is a Christian, but they despise the beliefs of traditional Christians.”

How would ‘a paucity of strong religious views … not have a significant impact’?

GWU’s Banzhaf (below), known for both his anti-smoking legal crusades and defense of campus free speech, warned that Lindgren’s findings are a bad sign for the future of legal education.

In a press release last month, the law professor connected the research to other studies that have found three-quarters or more of law professors are liberal, while perhaps 15 percent are “even moderately conservative.” It’s even more skewed at the top law schools.

“[I]t’s hard to see how a relative paucity of conservative and/or strong religious views would not have a significant impact” on the willingness of law students to voice similar views, Banzhaf wrote, worsening the “diversity and inclusiveness” of the law school.

He argued that the same “legal justification” for race-based affirmative action should also apply to conservative and religious professors, who fall into the same “underrepresented minorities” category:

It’s very important to understand more about the views of those teaching many of the leaders of tomorrow, especially in the legal profession, because it may affect their teaching and their influence upon those who will be making many of the most important decisions for all of us in the future …

MORE: Law professor submits conservative diversity statement

Banzhaf referred The Fix to a related 2019 study from James Phillips, nonresident fellow at Stanford University’s Constitutional Law Center. It concluded that “general Christianity, Catholicism, and other specific Christian faiths” were portrayed more negatively than all other religious beliefs in legal scholarship.

Phillips reached the same conclusion as Banzhaf: The composition of legal scholars matters because they “often impact future laws,” and “these trends may portend court decisions, statutes, and regulations in the next few decades.”

UChicago’s Leiter threw cold water on Lindgren’s portrayal of legal academia as unusual in broader academia. His blog post last month pointed out that 73 percent of academic philosophers and 92 percent of members of the National Academy of Sciences identify as atheists – a far cry from the “only 24” percent of law professors.

Christians are “overrepresented” in U.S. legal academia when compared with other academic disciplines and also law professors in England, he told The Fix.

Only once in the past 10 years can Leiter recall knowing of a candidate’s religious beliefs, he wrote in an email, calling their religious beliefs “irrelevant to their competence to teach and write.”

The biggest source of religious discrimination in hiring that he has observed is from religiously affiliated law schools, such as Catholic University of America and Baylor University.

MORE: University’s new chief of promotions cost it hundreds of thousands in lawsuit

IMAGE: SK Design/Shutterstock, Northwestern University, C-SPAN screenshot

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.