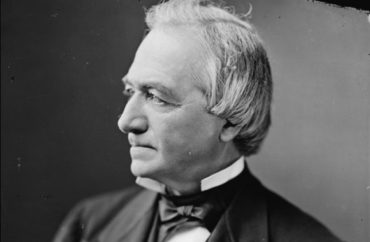

Rutgers University-Newark university leaders recently voted to remove the name of a former Supreme Court justice and prominent alumnus from a campus building.

Rutgers University Board of Governors approved a resolution Oct. 6 to strip the name of Joseph P. Bradley from “Bradley Hall,” which houses two academic departments, a learning center, theatre and campus post office.

Bradley graduated from Rutgers College in 1836 and was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1870, the university’s website states. In 1971, the Board of Governors approved naming the building after Bradley, who also served as a Trustee of Rutgers from 1858 to 1892, according to university documents.

While the former Associate Justice of the Supreme Court’s name has appeared on the building for nearly 50 years, officials cited Bradley’s judicial record as the reason for the change.

The “long-prevailing popular narrative about Justice Bradley was believed to incorrectly laud him as an advocate for civil rights, and has caused grave concerns among members of the Rutgers Law School,” the resolution for the name change states.

It added that in fall 2020, a committee of faculty, staff and students appointed by Chancellor Nancy Cantor “determined that contrary to the contemporary record, Justice Bradley played a role in perpetuating systemic racism and ushering in legalized discrimination in the period after the Civil War.”

Peter Englot, senior vice chancellor for public affairs at Rutgers–Newark, added that the study revealed Bradley “was more than just ‘a person of his time,’” according to a statement published by Tap Into Newark.

“Rather, at a time when the forces favoring and opposing Reconstruction were closely balanced following the Civil War, Bradley instead chose to use his position to tip that balance toward undoing Reconstruction, regressing on civil rights, and opening a new era of oppression and terror.”

Stripping Bradley’s name was also approved of by Cantor and Rutgers President Jonathan Holloway, the resolution states.

The university media affairs office did not respond to requests for comment last week from The College Fix.

Of particular concern is a court opinion Bradley wrote in 1883, which declared the first two sections of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 “unconstitutional.”

It sought to outlaw discrimination against African Americans in restaurants, public transportation or other private establishments. Bradley argued, however, that such protections do not apply to private businesses, but the actions of state governments.

Writing in his majority opinion, Bradley argued that to “deprive white people the right to choose their own company would be to introduce another kind of slavery.”

In 1872, Bradley also agreed with the court’s decision in Bradwell v. Illinois. The case concerned Myra Bradwell, who studied law with her husband, James Bradwell, but was denied admittance to the Illinois State Bar because she was a woman.

In a petition to the Supreme Court, Bradwell included proof that she possessed the “requisite qualifications” to practice law. She also claimed that her right to pursue a legal career was a privilege protected under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Bradley, however, argued that the right to practice law was not constitutionally protected under the Fourteenth Amendment. He also pointed to the laws of nature, claiming that women have a responsibility to care for their families, as the “timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.”

“…The harmony, not to say identity, of interest and views which belong, or should belong, to the family institution is repugnant to the idea of a woman adopting a distinct and independent career from that of her husband,” Bradley wrote.

“…The paramount destiny and mission of woman are to fulfil the noble and benign offices of wife and mother. This is the law of the Creator. And the rules of civil society must be adapted to the general constitution of things, and cannot be based upon exceptional cases.”

According to Englot, there is still a “firm commitment” to discuss Bradley in a permanent public display, mirroring the approach taken to buildings named after the founding families and former presidents of the university.

Instead of bearing the name of the former associate justice, “Bradley Hall” will now simply be known by its Warren Street address.

In a critique of the decision to remove Bradley’s name, Josh Blackman, a constitutional law professor at the South Texas College of Law Houston, argued that the “Civil Rights Cases is still good law. The Supreme Court reaffirmed the state-action doctrine in United States v. Morrison.”

“I doubt any 19th century Justices is safe from cancellation,” Blackman wrote for Reason. “The 20th century Justices will be on the chopping block soon enough.”

ALERT: Check out our Campus Cancel Culture Database

IMAGE: Library of Congress

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.