OPINION

“White privilege” is all the rage on college campuses around the country, even Christian colleges like Moody Bible Institute, Azusa Pacific University and Seattle Pacific University.

SPU’s own Tali Hairston, director of the Perkins Center for Reconciliation, recently told Christianity Today that white evangelical students “have not had to understand” that they have a “deficit of cultural literacy” when it comes to their own privilege.

SPU’s own Tali Hairston, director of the Perkins Center for Reconciliation, recently told Christianity Today that white evangelical students “have not had to understand” that they have a “deficit of cultural literacy” when it comes to their own privilege.

Schooling themselves in white privilege is the Christian thing to do, he says.

As an evangelical with more “cultural literacy” than the average white person, I’d like to ask Hairston and those who think like him to reconsider their assumptions about the core of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

I am a minority – half Chinese – and have been deeply influenced by international service to the poorest around the world in places like Thailand and Honduras.

My Chinese ancestors barely made it into the United States on the eve of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. I was the only Chinese-American in my high school and I am the only minority in my immediate group of friends.

My “white” side comes from Polish and Irish stock, hardly ethnic groups to which American and world history have been kind.

From this vantage point, I’ve grown deeply skeptical – and frankly, quite tired – of SPU’s hubristic fixation on liberation theology’s social justice agenda.

The assault on “white privilege” is nothing more than an ad hominem fallacy, built upon incredible assumptions about a diverse group of nearly 224 million people as of 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Liberation theology sinfully wrests Christ and the message of grace into a political tool and this debased gospel wrongfully fixates our spiritual gaze on the temporal rather than on the transcendent.

Instead of speaking directly about the economic, social and governance issues that may exacerbate America’s inequalities of wealth and opportunity, the argument for white privilege instead assaults a one-dimensional image of the Oppressive White Man.

If such an approach is unacceptable in philosophical or logical discourse, why have we allowed it to gain so much traction in our modern discussions of poverty and inequality?

To point the finger at all whites is illogical, unhelpful, and downright offensive.

Try explaining white privilege to the 5.1 million white children living in poverty in the United States, as estimated in 2013 by Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center. There are deeper systemic problems to be fixed than the perceived aristocratic superiority of a supposedly homogeneous group of Americans called “whites.”

Though I’m no biblical scholar, I don’t think that you need a master’s of divinity to see that Christ’s purpose was to demonstrate supernatural redemption and grace, not primarily promote fleshly transformation.

Though I’m no biblical scholar, I don’t think that you need a master’s of divinity to see that Christ’s purpose was to demonstrate supernatural redemption and grace, not primarily promote fleshly transformation.

At the core of the gospel lies the truth of a transcendent Savior who lived the life – and died the death – that we could not do ourselves, so that we might be reconciled to him. Out of this supremely powerful narrative flows the motivation to love one’s neighbor and care for the poor, widows and orphans.

Instead of leaning into this transcendent story of grace, Christian social justice as understood today, motivated by liberation theology, debases the gospel.

It insists that the primary mission of Christianity and Christian action in the world is to promote distinctly progressive and occasionally Marxist incarnations of civil society, government and economic structures.

Using the gospel in such a manner irresponsibly paves the way for endless partisan applications of Christ’s message. When we do this, we cease to be Christians who do politics and transform into politicians and activists who happen to be Christian.

Perhaps I direly misunderstand the basic message of liberation theology, Christian social justice or the arguments against white privilege. Perhaps I just do not understand how I have been racially disadvantaged and am therefore not sufficiently frustrated.

Am I so blinded by some sort of hybrid white privilege that I am unable to exercise “proper” Christian solidarity with the disenfranchised?

But whether you agree with me or call me part of the problem, we as a Christian community should be able to agree that we need to start having conversations about our conversations, rather than dismissing alternate viewpoints as heresy, racism or ignorance.

If I’m being invited to freely participate in “the conversation” about race, religion and politics, why is my voice not being heard? Surely we can do better than a never ending echo-chamber.

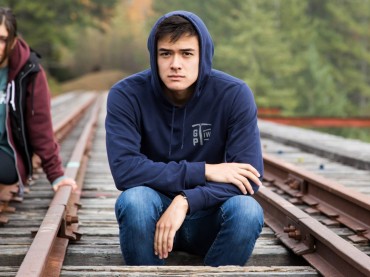

College Fix contributor TJ Jan is a student at Seattle Pacific University.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

IMAGES: TJ Jan, Seattle Pacific University

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.