A controversial Chinese national security law now has some American universities scrambling to protect their students, allowing some to submit work anonymously to evade law enforcement.

In July, China passed the law allowing the country to crack down on dissent, even from those residing outside of the country. It is the same law China has used to quash protests against the country’s attempts to erode the autonomy of Hong Kong.

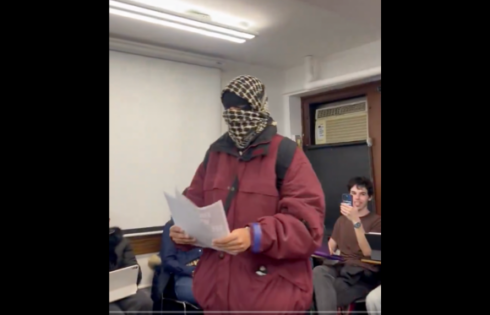

In response, schools like Princeton and Harvard have implemented policies allowing students to hide their identities, in the event the student says anything China considers politically “sensitive.”

At Princeton, students will be allowed to use codes instead of their names to shield their identities from Chinese authorities. According to the Wall Street Journal, Harvard Business School has contemplated excusing students from discussing politically sensitive topics if they are worried about the risks.

In England, Oxford University has granted students studying China full anonymity and has replaced group discussions with one-on-one sessions between students and professors.

The anti-dissident law allows China to punish any speech it determines to be “secessionist, subversive or terrorist,” even if the individual lives outside the country and isn’t a permanent resident of China.

In early August, China issued six arrest warrants for pro-democracy activists living around the world, including one for Samuel Chu, a U.S. citizen who runs the Washington, D.C.-based Hong Kong Democracy Council.

The issue has intensified during the coronavirus pandemic, as a great number of lessons are taking place online through videoconferencing. If the Chinese government were able to obtain recordings of these lessons, it could identify pro-democracy students and professors and issue warrants for their arrest.

“We cannot self-censor,” said Rory Truex, an assistant professor who teaches Chinese politics at Princeton, to the Wall Street Journal in August. “If we, as a Chinese teaching community, out of fear stop teaching things like Tiananmen or Xinjiang or whatever sensitive topic the Chinese government doesn’t want us talking about, if we cave, then we’ve lost,” said Truex.

During the 2018-19 academic year, there were nearly 370,000 Chinese nationals, or 34 percent of all foreign students, enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities, according to the Institute of International Education. If any of these students are identified as dissidents by the Chinese government and travel home, they could be arrested and imprisoned for life.

This is all happening as the FBI has recently arrested a number of university professors and researchers for secretly working with the Chinese government. That includes the former Chair of Harvard University’s Chemistry and Chemical Biology Department, Charles Lieber, who was indicted in June for making false statements about his involvement with a Chinese “Thousand Talents” program.

Further, in May, Ohio State rheumatology professor and researcher Song Guo Zheng was caught attempting to flee the country after participating in a Chinese talent program. Also in May, researcher Xiao-Jiang Li, 63, of Emory University, was sentenced to one year of probation on a felony charge and ordered to pay $35,089 in restitution for filing false tax returns in which he failed to report at least $500,000 in income from work at Chinese universities.

And in late July, Professor Simon Ang, head of the University of Arkansas High Density Electronics Center, was indicted for failing to reveal his connections to China when he applied for grants from NASA.

“There is no way that I can say to my students, ‘You can say whatever you want on the phone call and you are totally free and safe here,’” said Harvard Business School political science Associate Professor Meg Rithmire to the Wall Street Journal. “It’s more about harm mitigation.”

More: Former West Virginia University physics professor to serve jail time for hiding ties to China

IMAGE: M_SUR/Shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.