Over the past several years, universities all over the American South have been forced to confront their racist pasts, as students and professors have urged either removing or renaming landmarks dedicated to notable Confederates.

The Chronicle of Higher Education maintains a list of 36 such statues and monuments, 12 of which were either removed or moved to a different location in the wake of a white supremacist march that took place in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017.

But universities elsewhere in the country are just now beginning to recognize their role in harboring racists and eugenicists during the Progressive Era of the early 20th century. And in some cases, those universities choose to ignore their problematic progressive founders and instead punish those with lesser ties to their campuses.

When students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison visit their system administration, they go to Van Hise Hall, located at the center of the sprawling campus. The building is named for Charles Van Hise, who was appointed university president by progressive Gov. Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette in 1903.

A progressive eugenicist, Van Hise supported forced sterilization, arguing that “Human defectives should no longer be allowed to propagate the race.” This was in keeping with other early 20th century eugenicists, who held that humanity could be bettered by keeping less desirable people from reproducing. Van Hise once declared, “He who thinks not of himself primarily, but of his race, and of its future, is the new patriot.”

Race and the Left

The impetus behind progressive eugenics was often racism. Influential Wisconsin sociology professor E.A. Ross shared then-President Woodrow Wilson’s belief that Africans and South Americans were still savages of “low mentality,” and offered eugenics as a cure.

Economist John R. Commons, the author of many foundational texts on labor relations, was also an unapologetic racist. In 1907, Commons wrote an entire book dedicated to explaining why blacks are mentally inferior to whites.

He offered wisdom such as “The negro could not possibly have found a place in American industry had he come as a free man,” defended slavery as an institution, and suggested the only hope blacks had for economic success was to breed with whites.

To this day, economics students at UW-Madison may join the John R. Commons Club, and the social sciences building on campus hosts a John R. Commons room in his honor.

Current John R. Commons Club president Rosemary Kaiser told The College Fix via email that she was unaware of any of Commons’ racial beliefs “or even the time period he existed in.” She said she did not think any of the club’s members knew Commons’ history on race.

When first contacted by The Fix, Kaiser said she was unaware of any past attempts to change the name of the club. On February 28, after initially being contacted by The Fix, the John R. Commons Club held a meeting where Kaiser brought some of Commons’ history to the club’s attention. She said some members were “surprised” by his past statements on race.

“Clearly, these views do not represent our views as students,” Kaiser told The Fix. “At this point we are still discussing how we intend to move forward.”

Last September, Stanford University removed the name of Father Junipero Serra, the 18th century founder of the California Mission system, from two campus dorms and from the school’s official mailing address. In the late 1700s, Serra had a role in founding nine missions in which Native Americans were held as slave labor.

However, at the time of the Serra scrubbing, Stanford declined to remove the name of David Starr Jordan, the school’s first president, from its psychology school.

Jordan was a well-known eugenicist who once chaired the first Committee on Eugenics of the American Breeders Association. Another foundation chaired by Jordan published Sterilization for Human Betterment, a work that inspired Nazi laws mandating sterilization. Stanford’s administration did not respond to requests to comment for this article.

Schools Take Action

Some schools have begun investigating the roles played by their progressive racist alumni. Last month, University of Southern California Provost Michael Quick convened a “Task Force on University Nomenclature” to investigate concerns the campus community has about campus building names and monuments.

One of those buildings drawing the most concern on the USC campus is named after former President Rufus B. Von KleinSmid, an enthusiastic proponent of eugenics who supported forced sterilization.

“We must all agree that those who, in the nature of the case, can do little else than pass on to their offspring the defects which make themselves burdens to society, have no ethical right to parenthood,” Von KleinSmid wrote in The Lancet-Clinic.

In an email to The Fix, USC spokesperson Jenesse Miller emphasized that the administration was behind the formation of the task force and “supports the work it will do going forward.” Miller noted that the task force “won’t make decisions about individual building names.”

In the past few years Princeton University has been grappling with the memory of its most famous alumnus, Woodrow Wilson, during whose tenure as president of the university no African Americans were admitted. As president of the United States, the staunch progressive segregated the federal government. And yet for over a century, Wilson has been central to Princeton’s identity.

In 2016, Princeton removed an “unduly celebratory” mural of Wilson from a campus dining hall and began putting up more “diverse” art to deal with the complications of Wilson’s legacy. The university, however, kept Wilson’s name on its public affairs school.

Late last month, a panel at the University of Minnesota recommended scrubbing the names of four avowed racists and anti-semites from campus buildings in the Twin Cities area.

While not specifically naming the vanquished faculty as progressive eugenicists, the panel’s report does note that “many exclusionary and discriminatory practices at the University in the early 20th century occurred under the mantle of liberal progressive values through an adherence to ‘scientific’ racism despite the widespread challenges to its empirical bases.”

Missing the Mark

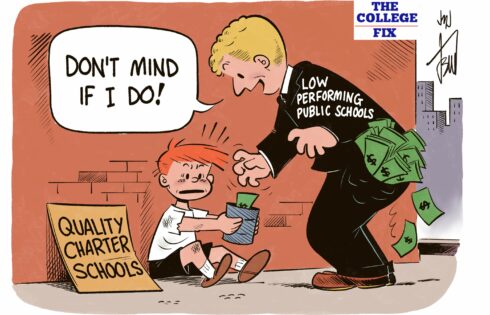

Like Stanford, some schools have gone after lower-hanging fruit while protecting their progressive forefathers.

At the UW-Madison, a committee issued a report in August of 2018 recommending the school rename two memorials in the campus’ Memorial Union. The landmarks, named for alumni Fredric March and Porter Butts, have been renamed after information surfaced connecting March and Butts to the Ku Klux Klan.

Interestingly, there is no evidence the “Ku Klux Klan” on the UW-Madison campus had any connection with the more famous Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the national organization of white supremacists. In its press release, the committee conceded that “no information has been found that connects the organization to any ideology.”

Nevertheless, members moved forward with the renaming simply “in consideration of the impact on students and other community members of affiliation with any organization called the KKK on students and other community members.”

According to UW-Madison spokeswoman Meredith McGlone, the university is not currently considering any more name changes to landmarks, buildings, or major organizations.

McGlone noted the John R. Commons Club is still active within the economics department but that it is not officially registered with the university as a student organization.

“Keep in mind that we’re a big place and organizations that are affiliated with the university come and go and can change their names if they wish,” McGlone said in an email to The Fix.

The John R. Commons room in the Social Sciences building remains.

MORE: Students demand Catholic university denounce Saint Junípero Serra as mass murderer

IMAGE: Edward Conde/Flickr

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.