Regardless of how many masks the CDC ends up recommending you wear, they all depend on you wearing them properly.

This includes not touching or fidgeting with them, as well as ensuring they form a tight seal around your face – something that is not possible with the vast majority of masks today worn by Americans.

Even a tight seal might not be enough.

Virus researchers found that even “completely sealed” masks – including the gold-standard N95 masks that are specifically designed to stop even aerosolized (non-droplet) virus from escaping – “were not able to completely block the transmission of virus droplets/aerosols” that cause COVID-19.

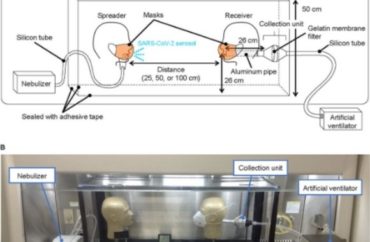

Published in the American Society for Microbiology’s journal mSphere, the study shares findings from “an airborne transmission simulator of infectious SARS-CoV-2-containing droplets/aerosols produced by human respiration and coughs.” Virologists at the University of Tokyo and a pulmonologist at Japan’s Keio University studied how well different kinds of face masks blocked transmission.

While “cotton masks, surgical masks, and N95 masks all have a protective effect” – more so when worn by “a virus spreader” – surgical and N95 masks are still not a silver bullet against COVID-19 even when users put them on properly.

Like the “early release” CDC study that was widely reported as recommending the wearing of two masks simultaneously, the mSphere study used mannequin heads (above) to test mask efficiency against viral transmission.

The N95 masks were attached in two ways: “the mask fit naturally along the contours of the mannequin’s head, or the edges of the N95 masks were sealed with adhesive tape.”

The N95s had 80-90 percent “protective efficiency” for the “virus receiver” mannequin, and even when taped to the face, “infectious virus penetration was measurable,” they found. It was far worse for cloth masks – only 20-40 percent “reduction in virus uptake compared to no mask.”

Mask performance was better on the “virus spreader” mannequin, with more than 50 percent transmission blockage by cotton and surgical masks.

The amount of exhaled virus is key to determining whether a mask does any good for either spreader or receiver. When the spreader’s viral load was reduced to 100,000 plaque-forming units, “infectious viruses were not detected, even in the samples from the unmasked receiver.” (Tested viral load went all the way up to 100,000,000 PFU.)

All samples had detectable “viral RNA,” however, regardless of whether they were infectious. (People who test positive for COVID-19 but don’t show symptoms tend to have low viral loads and are highly unlikely to spread it even in the home, the most dangerous venue for transmission.)

Read the study, which was published Oct. 21 but largely ignored in the media.

h/t Ben Marten

IMAGE: mSphere

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Add to the Discussion