System has become ‘an entitlement for presumably relatively affluent individuals’

You’d think during a prosperous period with record-low unemployment, those who took out federal student loans would be better equipped to pay down the balances.

That’s not what’s happening, however, and higher education economist Richard Vedder has an explanation: Students think Uncle Sam is going to forgive their debt.

In an essay for the Martin Center for Academic Renewal, Vedder analyzes an October report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The numbers are alarming: Borrowers with more than $100,000 on their balances are 7 percent of the borrowing population, but owe more than a third of outstanding loans. The report’s analysis of student loan debt by ZIP code confirms that “relatively affluent borrowers are disproportionate participants in the student loan program,” Vedder writes.

Those who graduated in 2010 had repaid less than 10 percent of their loan balances five years later, and student loan debt rose twice as fast as tuition fees between 2008 and 2018, which means “much student borrowing appears not to meet direct instructional costs,” the economist says.

The New York Fed report expresses surprise at the “very large share of borrowers who have not reduced their balances” between the second quarters of 2018 and 2019:

Although the share of borrowers in the “balance not declining” category edges slightly lower as incomes increase, it should be noted that a surprisingly large share […] of borrowers are not actively reducing their balances even in relatively wealthy areas.

As Vedder says, “a majority of students are not reducing their loan balance—at all.”

He has long railed against cheap federal student loans for incentivizing higher tuition fees, which in turn fund “sizable administrative bloat on most campuses,” while not helping poorer students graduate. He said the lowest quartile of the income distribution actually graduates at lower rates than in 1970:

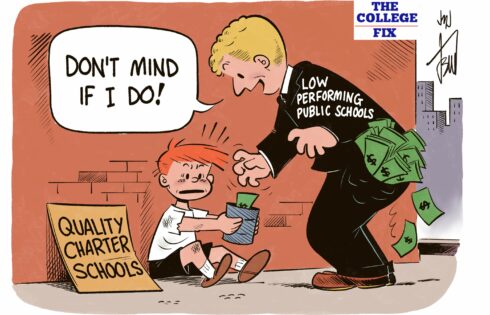

Schools that encourage students to take out loans have no “skin in the game,” facing no financial consequences when their students disproportionately default on their obligations. In short, the student loan program is dysfunctional and in need of substantial modification—arguably elimination.

Instead, high-profile presidential candidates such as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are promising to cancel all or substantial student debt, which would make students “sucker[s]” for repaying their balances.

“Slowness to repay is particularly high among recent borrowers—individuals graduating in the era of the socialist ascendency within the Democratic Party,” Vedder says.

He’s found some evidence that students aren’t using their artificially cheap guaranteed federal loans for their intended purpose, but rather for “entrepreneurial ventures.” One of Vedder’s former students, for example, is doing well in his expanding business but he has little incentive to repay his federal loans when their interest rates are lower than on private-sector loans.

Taxpayers should be concerned that student loans today are largely “an entitlement for presumably relatively affluent individuals”:

It is one thing to support the poor kid borrowing $25,000 to earn a bachelor’s degree from a regional state university to get a $40,000 job. It is another thing to finance tomorrow’s plutocrats, some who have borrowed $150,000 or more and are already making $200,000 or more a year, but who are not paying down their loan balances when they could easily afford to do so.

Vedder offers various proposals to fix the situation, including an end to the parent borrowing program PLUS and student tuition tax credits, a cap on years and borrowing amounts, and forcing colleges to “become at least limited co-signers on loans.”

Read the analysis and Fed New York report.

IMAGE: Cookie Studio/Shutterstock

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Add to the Discussion