In the fall semester of my junior year, I applied for a course at Cornell University that would teach me career-building skills that I could then apply on a trip to New York City. Once there, students are connected with alumni in the top of their fields.

As a student journalist who understood that making connections in the media industry is crucial for young reporters, I eagerly enrolled. I knew such a course would put me on the right track.

I was rejected, but I took the denial in stride. I understood the chances of getting accepted were low, as admittance to the class is highly competitive.

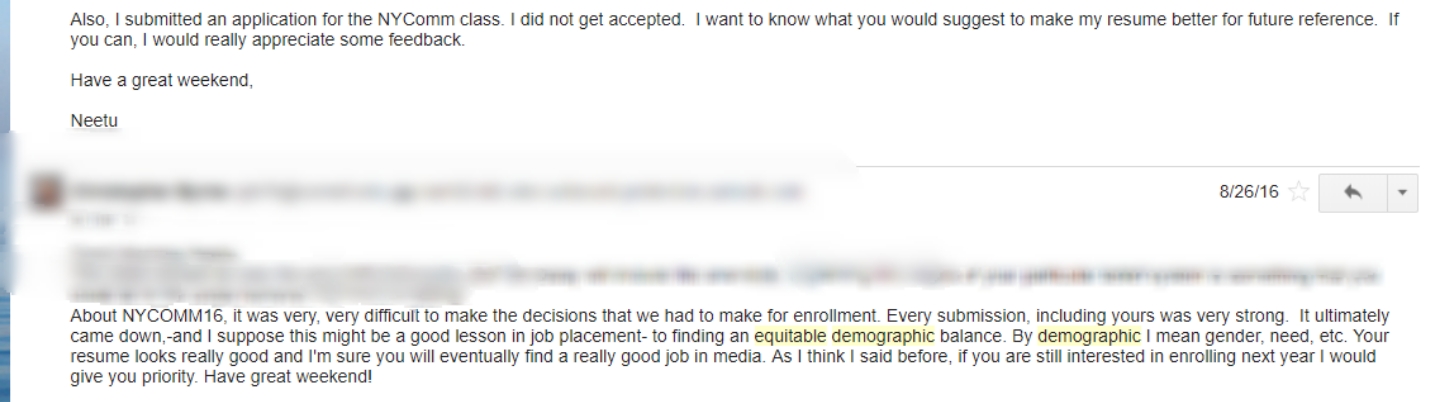

Still, I asked the professor for feedback so I could improve myself as a candidate for future opportunities. It was then that I learned the real reason I was denied.

“Every submission, including yours, was very strong. It ultimately came down,-and I suppose this might be a good lesson in job placement-to finding an equitable demographic balance. By demographic I mean gender, need, etc.”

In an appeasing tone, he added I needn’t worry, that I had a strong resume and he was sure I’d land a great media job, but I could apply next year with priority if I was still interested.

Reading this response sent a shockwave of indignance through me. There’s nothing that can quite prepare you for learning that you’ve been judged not by the qualifications of your resume, but the color of your skin.

I believed the professor assumed I was privileged and I would not need any help with my career because my minority group, Indian American, is often successful in America.

As I graduate this month and begin my media career in Washington D.C., I still look back on this experience and the phrase the professor tossed my way: “equitable demographic.” It stings to this day because I was rejected based on factors I could not change about myself.

It made me realize that even if I worked to meet and go above the standards, somebody who was less qualified could still get the position because of “equitable demographics.”

While it claims to be about bringing equal opportunity to all, affirmative action is anything but equitable. In fact, it is an insult to everybody involved. It encourages mediocrity and discourages people to try their best.

The intention may be to reduce inequality and provide opportunity for all, but as my experience shows — affirmative action is discrimination.

It also isn’t much of an educational opportunity if the very people accepted through such initiatives end up settling for easier majors or dropping out, as one study shows.

This furthers any stigmatization the efforts attempt to break. It also sends the message that such groups need to be held to low standards in order to get anywhere in life.

Making matters worse, several studies have also shown that affirmative action policies are financially inefficient and can even lead to polarization among diverse groups. Take India, which has experienced deathly riots over the issue of preferential-based policies. Down the road, it would not be surprising if the U.S. experiences similar problems, especially since we have diverse groups of people who have different ideas of the way American policies should work.

In order to progress, our minds cannot be stuck in the past. Affirmative action policies seem to be more about socio-political revenge than truly helping those who are not privileged. Universities and other organizations need to keep the high standards and reward those who meet them. On a societal level, we can mentor our youth and help them rise to the standards.

While I have had many opportunities in my life, it does not negate the multi-faceted struggles I have faced as an immigrant attempting to balance my Indian and American heritages.

As a small town girl adjusting to the rigors of an Ivy League university, I’ve confronted many challenges, including assumptions peers have made about me simply based on my ethnicity.

When I applied for that Cornell class, I’d come with my share of hurdles, yet I did not want to be judged on those, nor my ethnicity. I’d been a strong candidate and did not deserve to be edged out because of the color of my skin, or because of anyone else’s for that matter.

MORE: The problem with affirmative action in one picture

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.