A UCLA law professor critiques affirmative action as detrimental to the very people it strives to aid: minority students.

Professor Richard Sander, though liberal-leaning, has deemed affirmative action practices as harmful, a notion that contradicts a liberal view in college admissions, said Stuart Taylor, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Taylor credits Sander for evaluating the facts rather than searching for information only to bolster his political ideologies, he said.

Mismatch is born

Sander began teaching law at UCLA in 1989. After a few years he garnered an interest in academic support and asked permission to analyze which strategies most effectively assist struggling students.

After reviewing statistics on performance, especially those of students with lower academic merit, he noticed correlations between race and academic success.

“I was struck by both the degree to which it correlated with having weak academic entering credentials and its correlation with race,” Sander said in a recent interview with The College Fix. “And as I looked into our admissions process I realized that we were giving really a large admissions preference.”

Sander noticed that students admitted into the law school with lower academic credentials than their peers had significantly lower percentages of passing the Multistate Bar Examination, Sander said. This especially pertained to minority  students who were given special consideration in the admittance process due to their race rather than their academic preparedness.

students who were given special consideration in the admittance process due to their race rather than their academic preparedness.

He then began thinking about whether or not these students would have better chances of succeeding if they went to a less elite university, he said.

He called this discrepancy a mismatch; when minority students with lower credentials than their peers are accepted into more challenging universities and then suffer academically as a result.

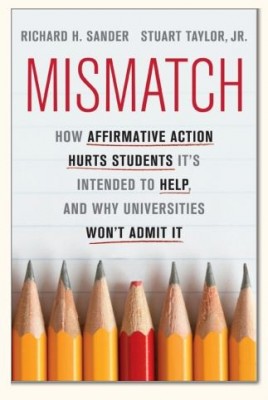

He and Taylor wrote about this phenomenon in the book they co-authored, “Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It.”

“Though their liberal leanings would indicate support for race-based policies, Sander and Taylor argue that the research shows that affirmative action does not in fact help minorities,” the 2012 book’s summary states. “Racial preferences in higher education put a great many students in educational settings where they have no hope of competing—a phenomenon that they call ‘mismatch.’ … Compelling evidence shows that racial preferences double the rate at which black students fail bar exams and may well in the end reduce, rather than increase, the aggregate number of black lawyers.”

Opposition to Mismatch

Vikram Amar, dean of the University of the Illinois College of Law, said he is not convinced that there is a mismatch that is harming minority students.

“It’s not that I think it’s terrible to ask the questions he’s asking,” Amar said in a recent interview with The College Fix. “I’m just not sold that there’s the case he is making that has proven his big claim.”

For example, a student who gets into Harvard Law School with the credentials more representative of the average law student at the University of Michigan would not necessarily fail. The benefits of attending the more rigorous school would outweigh the disadvantage of being less academically prepared, he said. Rather, it would be more beneficial to offer resources to help those students once admitted rather than send them to less-elite schools.

It is more difficult to measure the effect affirmative action has on employment than Sander suggests, Amar said.

Amar said in an article he wrote on the subject that Sander does retain more credibility than many Republican critics, however, because “he is critiquing a liberal policy from the perspective of someone personally committed to liberal causes.”

How Mismatch Works

There are three types of mismatch: learning, competition and social.

Learning mismatch occurs when less academically prepared students work alongside students who are more prepared. The former may start to feel lost and will have difficulty learning in the more rigorous environment, Sander said.

Competition mismatch also occurs in the classroom when struggling students begin earning lower grades than their counterparts. Ill-prepared minority students have a high rate of dropping out of difficult programs, such as science programs, when mismatched because receiving lower grades may diminish their confidence, Sander said. Students are more likely to succeed in less competitive environments.

The final type of mismatch is social. Students are naturally more likely to forge friendships with others at similar skill levels. Mismatched minority students may have more difficulty befriending more competitive students which can be isolating, Sander said.

Learning mismatch is the operative mismatch in the law school instance, he said.

Sander became even more perturbed by the Supreme Court’s rulings in Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger in which the constitutionality of the affirmative action policies of the University of Michigan and University of Michigan Law School, respectively, were questioned.

Sander said he felt these rulings only served to encourage universities to be dishonest about their racial preferences. In response, he wrote a highly controversial article on mismatch.

His article was sensitive to the point that the University of Pennsylvania Law Review, which initially agreed to publish his article, then retracted their offer. Stanford Law Review then accepted his article.

However, a group of law professors began pressuring the Stanford Law Review against publishing the article. The Stanford Law Review did publish Sander’s article, but accompanied it with multiple criticisms, more than Sander was originally informed of, Sander said.

“That was really problematic because it just gave the impression that the whole academic world was united in thinking that this was a bad piece of scholarship, when in fact it was a very vocal minority that was upset about it,” Sander told The Fix.

These obstacles served as great deterrents to his continuing research, he said. He even lost friends because of his articles and findings.

“Academia is supposed to be about open inquiry, and one of the prime examples of where academia has fallen very short of its ideals,” Sander said.

Transparency in universities

One of his concerns was the lack of transparency in the university admittance processes all over the nation, he said.

Many schools were not honest about the degree of emphasis they put on race in relation to grades and test scores. This was one of the major points in the book he and Taylor co-authored.

Schools also failed to reveal the effectiveness of these preferences. Many law schools champion an average Multistate Bar Examination rate, but fail to offer information regarding the average passage rates of those admitted with lesser credentials.

This only works to “lure people in only telling them what the average bar passage rate is for the whole school, and in fact often claiming that all their students have roughly the same chances of passing the Bar,” Sander said.

Many of these students will spend large amounts of money with significantly lower chances of passing the exam and becoming licensed to practice law, he said. If a school provided information on the success of students at different academic levels, then at least students would be informed when deciding which law school to enroll in.

Affirmative action became a large movement to combat the insensitivity of universities to race. These actions served to help racial healing, but the initial idea was that racial preferences in admittance would serve to bridge the gap between white and minority students in the university setting. It was meant to be a temporary fix, but test score gaps, though improving for a while, stabilized in the 1980s and have failed to close further, Sander said.

And now it is difficult for schools to retract their affirmative action policies.

Affirmative action ultimately leads to an unwarranted fixation on race, Sander said. While he does think it is healthy for schools to be race conscious, this practice has ultimately been abused.

Affirmative action today

Taylor said he does not think race should be on university applications.

History has shown that when race is included into the acceptance process, universities use it excessively, he said. Race will always be considered to some extent, but he does not believe it is a good policy to consider race in the admittance equation.

“There’s always going to be racial diversity because there’s always going to be students from every ethnic minority group, some who are outstanding, and also there will always be some degree of racial preference no matter what the law says,” Taylor said.

Ultimately, mismatch sets up minority students who do not have the same academic preparedness for failure, Taylor said.

In 2006, Sander and other scholars asked the California Bar, one of the largest bars in the U.S., to analyze data from previous examinations such as LSAT scores, undergraduate grades and race in relation to bar passage rates.

(Though Amar said in his article that he does not necessarily agree with Sander’s views on affirmative action, he does support examining the data to see what it reveals.)

When Sander approached the California Bar about accessing this data — 30 years worth of background information — law schools organized resistance and convinced the California Bar to deny such inquiries saying that such disclosure would threaten the privacy of these who had taken the test.

Sander responded by suing the bar with some public interest lawyers. The Supreme Court ruled that the bar had the responsibility to make this information public. But a way to ensure the protection previous bar-takers’ identities has not yet been litigated. Schools have also stopped sending data to the bar, so any eventual analysis of the data will be dated, Sander said.

“Normal standards of academic inquiry are just completely thrown out the window when political correctness rears its head,” Sander said.

The trial to try and make this data publicly available is set for next June.

“It’s close enough to taste, but we’re not tasting it,” Sander said.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

IMAGE: Shutterstock

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.