When viewed through the lens of economics and statistics, today’s prevalent campus hook-up culture favors men – by a wide margin – according to one professor’s analysis of data and surveys on the subject.

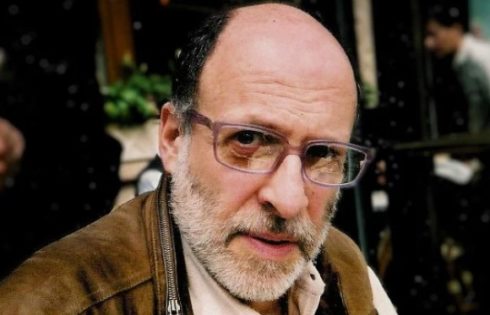

Despite being the “suppliers” of sex, women allow men to dictate the terms of its purchase, notes Dr. Mark Regnerus, associate professor of sociology at the University of Texas, Austin.

But if women affirmed their own value and refused to be seen as cheap goods, they would no longer be the chief victims of the hook-up culture, rather its chief antagonists, Regnerus’ analysis suggests.

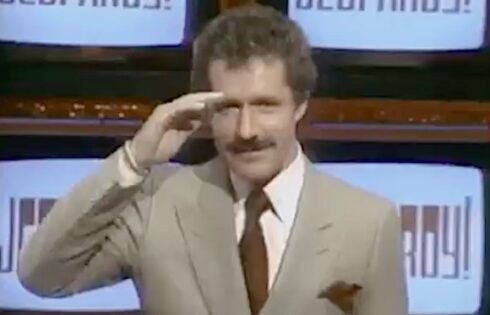

The professor, author of the recent book Premarital Sex in America: How Young Americans Meet, Mate, and Think about Marrying, recently explored his thoughts on the economics of casual sex on campus at the fifth annual “It Takes a Family” conference, hosted by the Ruth Institute in San Diego.

Regnerus argued sex is loosely interconnected as part of an economic and social sexual marketplace, and therefore not simply a private matter between two consenting adults.

He called it the “mating market.”

In today’s market, more men are interested in sex outside of committed relationships, more women are interested in marrying, and in the middle are both men and women interested in committed sexual relationships outside of marriage, the professor said, citing various studies.

In the terms of sexual economics, women are generally the “suppliers” of sex, and men constitute the “demand” for it and play the role of “consumer.” In other words, women are the gatekeepers of the goods for which men are willing to work and pay, he said.

As with all economic models, when various factors shift the equilibrium, the price of the good changes. The “hookup culture” – the proliferation of cheap and casual sex, especially on college campuses – occurs within a marketplace in which suppliers (women) are willing to capitulate to the cheap asking price of the consumers (men).

Women give men what men want and fail to secure reciprocal investment in return, Regnerus asserted.

Citing numerous studies conducted by Add Health, a longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents, he said half of college-aged males surveyed reported having known their partner for less than a month before first having sex, whereas more than a quarter of all female respondents had waited over a year before climbing into bed.

Another survey found men are 11% more likely to engage in “nonromantic sexual relations” – casual sex and “friends with benefits” relationships – than are women.

According to a third stat, 83% of college-aged males reported that their past nonmarital sexual relationships had lasted less than three months, whereas only 37% of women reported the same. More strikingly, 36% of men reported that their past sexual relationships lasted only one day, whereas less than 3% of women reported the same; only 4% of men reported a past sexual relationship that had lasted over a year.

A fourth survey, by the New Family Structure Study, found that males age 23 to 39 are more likely than women in the same demographic to have cheated or currently be cheating on their primary sexual partner.

Together, these numbers indicate that men are “paying less” for sex than their female counterparts in the currency of commitment, investment and exclusivity.

Men seem content with this “no strings attached” arrangement, but not so much the fairer sex. Regnerus mentioned one well-known study in which attractive young researchers propositioned opposite-sex strangers on Florida State’s campus with offers of casual sex. Three-fourths of the men were happy to oblige, but not a single woman accepted the offer.

How can women better position themselves, economically?

One way to increase the “price” of sex would be for women to collude with each other to “restrict” guys’ easy access to sex, demanding better treatment and therefore causing a leftward shift of the “supply” curve, Regnerus posited.

Such a collective decision would alter the dynamics of the entire sexual marketplace – say, on a college campus – and force men to “pay more” in exchange for sex, he said.

Rather than a plurality of men reporting one night stands, men would have to invest more in their relationships in exchange for the goods they seek from their female partners (e.g. dinners, flowers, 6 months of dating, a proposal, etc.) Regnerus also presented “factors influencing sexual exchange” in which he laid out six market factors that influence sexual currency.

The three market factors that lower the price of sex – therefore enabling a culture of casual, uncommitted sexual in which women are the true losers – are increasingly present at America’s universities:

1) There are larger pools of women than men, so supply outstrips demand; only 43% of college undergraduates are male.

2) Permissive sexual norms are prevalent; various studies have indicated that Generation Y’s sexual ethical standards are relaxing.

3) Finally, men have easier access than ever to digital pornography or other low-cost sex substitutes.

The only market factor that female students can directly impact to increase the price of sex – thereby causing men to improve their wooing efforts and treat the ladies with more respect – is to collectively increase their individual worth in guys’ eyes by refusing to be used for punctiliar pleasures.

Fix contributor Michael Bradley is a student at the University of Notre Dame.

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.