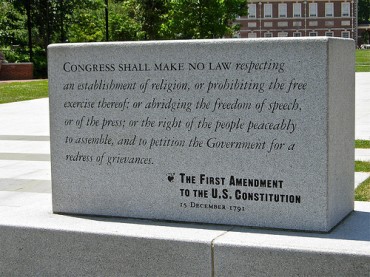

Faced with criticism, a small but steadily increasing number of universities ease rules that restrict free speech on campuses.

Administrators at the University of Mississippi – commonly called Ole Miss – certainly had every right to describe themselves at First Amendment friendly. After all, in 2009 its officials allowed the Ku Klux Klan to rally on campus grounds before a football game, and even provided the protestors police protection.

Nevertheless, when Ole Miss officials noticed the nonprofit Foundation for Individual Rights in Education had given the university a failing grade over the school’s written rules regarding free speech on campus, administrators were prompted to revise its policies, said Scott Wallace, assistant dean of students.

“We are a marketplace of ideas, that is what universities are,” Wallace told The College Fix. “And we cannot fully teach students and fully conduct research effectively without the opportunity to speak freely.”

Wallace and other campus officials worked with Foundation for Individual Rights employees to revise the university’s speech codes, and in January the nonprofit gave the school a “green light” – its highest ranking – and a signal it believes Ole Miss is completely First Amendment compliant.

The University of Mississippi was one of three new universities to make the nonprofit’s annual “best colleges for free speech” list, released earlier this month. The other two were Mississippi State and James Madison universities.

Robert Shibley, the education foundation’s senior vice president, said the three new campuses on the list are an indication of the small but growing number of universities taking steps to revise speech codes and lift restrictions on student expression.

Wallace maintains revisions at Ole Miss put into black and white what was already in practice there, but Shibley notes that pressuring universities to revise their speech codes is far more than just semantics.

“A college can certainly crack down on dissent whether or not it has policies that violate the Constitution,” Shibley said. “However, colleges generally are forced to justify such efforts as censorship by citing written policies that have been violated. When those policies don’t exist, it makes it much harder for colleges to engage in censorship because it denies them ‘cover’ for their actions.”

While there is some positive progress on campus speech code revisions, there is still plenty of work to be done, Shibley said. He points to the education foundation’s traffic light system, which ranks about 400 universities across the nation with red, yellow or green lights.

The nonprofit gives campuses a green light “if it does not maintain any policies that seriously imperil speech on campus,” its website notes.

“Only 16 schools out of the nearly 400 … have earned green-light ratings,” it states.

Nevertheless, the percentage of schools with a red-light rating has declined for four consecutive years, from 79 percent to 65 percent, according to the “Spotlight on Speech Codes” report the group published this year.

Changes at Ole Miss included speech code revisions that “clarified our language” so that in order to violate campus policies, the expression in question would have to be “more than merely offensive; it must be so objectively offensive, pervasive and/or severe, that if repeated it would effectively deny the victim access to the university’s resources and opportunities,” Wallace said.

The university also revised its policy over so-called speaker’s corners, where student speeches, debates and demonstrations are encouraged.

“They said it was not clear, in that it could be interpreted to mean free expression is only allowed in our designated speaker’s corners,” Wallace said. “That is not what we meant at all, so we clarified what we meant by adding one sentence: ‘nothing in this section shall be interpreted as limiting the right of student expression elsewhere on the campus, so long as the (conduct) does not violate any other applicable university policies.’ ”

As for James Madison University, another new campus to the education foundation’s “best colleges for free speech” list this year, its green light can be traced in part to its axing of a policy forbidding students from posting fliers that weren’t in “good taste,” Shibley said.

“Obviously taste is in the eye of the beholder,” he said.

At Mississippi State University, its IT usage policy prohibited “sending unsolicited, offensive, abusive, obscene, or otherwise harassing communications, hate speech, or bullying.”

Not anymore.

“Once again we have the problem that what is ‘offensive’ is in the eye of the beholder, and is not an appropriate judgment for the government to make,” Shibley said. “The same goes with hate speech and ‘abusiveness.’ What is hateful or abusive to one person may not be to another. This provision has now been eliminated from Mississippi State’s policy.”

Shibley said the slow but steady trend in favor of free speech rights at universities across the nation shows “you certainly can fight City Hall.”

“Outside of campus there is virtually no support for censorship or free-speech zones,” he said. “Students – conservative, libertarian, liberal or otherwise – when they meet with administrators, write letters to papers, organize and advocate for free speech, they are met with a lot of success.”

IMAGE: DC Writer Dawn/Flickr

Click Here to Like The College Fix on Facebook.

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.